Want rural superfast broadband? Do it yourself

- Published

Farmers are crying out for faster internet connectivity, says the National Farmers' Union

Rural communities, fed up with snail's pace internet connectivity and lacklustre progress by private telecoms companies, have been building their own broadband networks.

One such initiative, Northamptonshire-based Tove Valley Broadband, external (TVB), was set up by volunteer locals after they realised that faster internet speeds were not arriving any time soon.

The not-for-profit group engaged installation company Fibre Options to lay fibre optic cables in trenches dug by a local land drainage contractor.

"In the last year I've done a hell of a lot of walking across fields looking down holes," says Peter Watkins, TVB's technical director. "It's been something that's kept me active."

The group - after much effort - has succeeded in bringing internet speeds of more than 30 megabits per second (Mbps) to 457 people so far, says Mr Watkins.

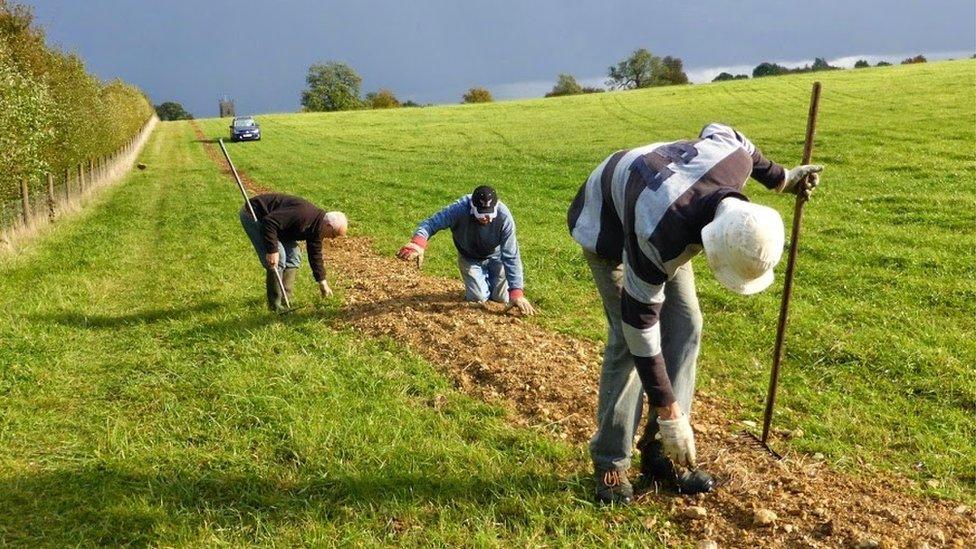

Huge trenching machines can dig and lay cable at the same time

The Tove Valley Broadband volunteers tidy up after another fibre optic cable has been buried

Domestic scheme members pay £100 to join, a £75 installation fee, then £120 a year.

Another project, Broadband for the Rural North, external, has been laying fibre optic cables right up to the backdoor of rural homes in Lancashire, given them blistering "hyperfast" download speeds of up to 1,000Mbps.

The service costs £30 a month for residential users after a £150 connection fee.

Hard-to-reach

Broadband Delivery UK, the body tasked by the government to roll out its £780m National Broadband Scheme, has been giving funding to a handful of such community projects, but the total currently stands at less than £5m, external.

The Scheme aims to provide 90% of UK premises access to "superfast broadband" of at least 24 megabits per second (Mbps) by 2016, and to reach 95% of premises by 2017.

But many people in rural and "hard-to-reach" areas have been excluded from this first implementation phase and are still making do with a fraction of those speeds.

Tim Muffett reports that volunteers will carry on supplying broadband to areas hard to reach

According to UK telecoms regulator Ofcom, the average UK broadband speed was 22.8Mbps as of November 2014.

While rural speeds averaged a third of that, some remote areas are making do with speeds as low as 1Mbps.

It's frustration at these glacial speeds that has prompted some local communities to take matters in to their own hands.

Fundamental right

Roger Carey is director of Village Networks, external, a community broadband initiative that was successful enough to become a self-supporting enterprise.

He believes that an adequate internet connection is a fundamental right.

"It's not fair to say to people: 'You've chosen to live in a remote rural environment, satellite broadband is your only option - it's very expensive, it's technologically unsatisfactory, but you've got to live with it'. That's an inappropriate response.

"There's no reason why those people should suffer an unsatisfactory alternative to the internet people in cities and towns have," he says.

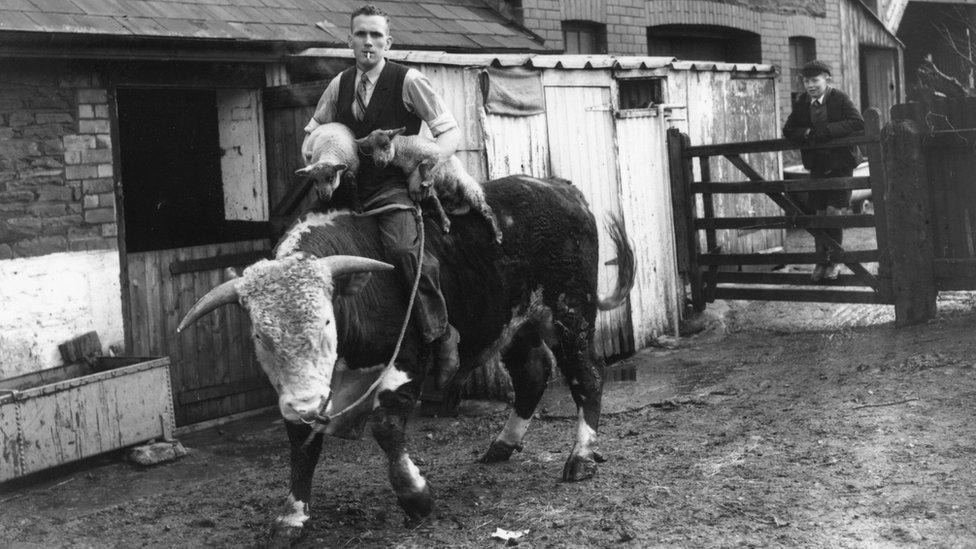

Some farmers feel they're stuck in the past when it comes to communications technology

For farmers, connectivity is also becoming increasingly important to their business.

"The response from our members is that they aren't getting access to the signal that they need and want," said Suzanne Clear, a senior adviser at the National Farmers' Union (NFU).

"That's really important for their business, but it's also really important for their social life, their wellbeing, and for contacting doctors and schools. Everything now is sent out by email and they haven't got that access."

The NFU's other concern is that UK farmers may miss out on agricultural technology advances due to poor connectivity, which could damage the country's ability to compete globally.

A tale of two fibres

Critics of the national broadband roll-out plan say the problem likes with the fact that BT mostly provides "fibre to the cabinet" (FTTC) rather than "fibre to the home" (FTTH).

FTTC, as the name suggests, brings fibre optic cables - which are significantly faster at transferring data than copper cables - to the BT cabinet closest to you.

The final leg of the connection then relies on the copper between your home and the cabinet.

Bill Murphy, BT's managing director of Next Generation Access, explained that the company "chose to deploy mainly FTTC technology because it allowed us to reach the most homes and businesses in the fastest possible time.

Telecoms companies argue that it's too expensive to install superfast broadband in rural areas

"FTTC currently delivers download speeds of up to 80Mbps - more than enough for today's consumers."

In rural areas, though, the copper connection can be several miles long, and signal strength weakens the further it has to travel - a process called attenuation.

"The technology that's available through the incumbent [provider] is not suitable for rural areas, as has been proven over and over again in every single county," says Hugo Pickering, chief executive of Cotswolds Broadband, external.

"FTTC is not a viable technology for rural areas ...copper has an effective lifespan and likewise it has a reach which cannot be exceeded due to the laws of physics."

BT has worked on some FTTH projects, but cost has proven to be a limiting factor.

"To do this nationwide would have been enormously expensive," says Mr Murphy. "Some estimates suggest around £28bn."

Up in the air

Where FTTH is too expensive or difficult to put in place, some communities have set up wireless networks, using high gain directional antennae to provide line-of-sight connections over long distances.

"If you're a commercial operator, that's incredibly expensive," says Professor Peter Buneman, one of the founders of Tegola, external, a research project helping to provide internet access to small, isolated communities across rural Scotland.

"You have to put up great big masts, you have to have maintenance contracts, and you're talking about £100,000-£200,000 just to serve a community of 10 people.

The Tegola project in rural Scotland is experimenting with wireless broadband

"No organisation is going to do that. Communities can do it for a fraction of the cost," he says.

Prof Buneman started Tegola "out of sheer frustration," he says.

"It was quite clear that the government was doing nothing, and BT just wanted to make money. Then people came round asking me how to do it."

Wireless networks are well suited to some areas, but not others. You need to have a fibre optic network nearby to connect to, he says, and the necessity for line-of-sight connection is a limiting factor.

But community broadband initiatives are perfectly achievable, says Prof Buneman, providing you're prepared "to roll up your sleeves."