Is equity release still a dirty word?

- Published

Many couples, like this one from Oxfordshire, are quite happy with their equity release plans

Whether you're considering a cruise, a new kitchen, or just giving money to the children, the thought of liberating that cash from the value of your house is enticing.

Or you may need it simply to pay the bills.

Yet last week the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) suggested that equity release - once "a dirty word" - still has problems with its public image.

More than that, it implied that consumers are paying too much for a product whose effect can be to eat up all their savings, leaving nothing to pass on to their descendants.

But the industry is fighting back. It argues that the fees it charges are justified, and says there's never been a better time to take out a policy.

So what's the problem with equity release - and what should home-owners consider before signing up to it?

Win-win?

If you are approaching retirement - or just need some cash - you can raise money against the value of your house.

Traditionally, equity released worked like this: a finance company purchases a proportion of your house. In exchange for cash they actually own a stake in the property, but they only get their money back (plus any profit from rising house values) when you die or move out and the property is sold. This is known as a home reversion plan.

These days 99% of equity release products are based on a different model: a lifetime mortgage. The homeowner retains full ownership of the property but borrows money using the house as security, just like a normal mortgage. But the mortgage term is only up when you die, meaning your estate pays back the money not you. In the meantime interest accumulates on the loan, just like with a traditional mortgage.

It all sounds like a win-win, both for the customer and the provider.

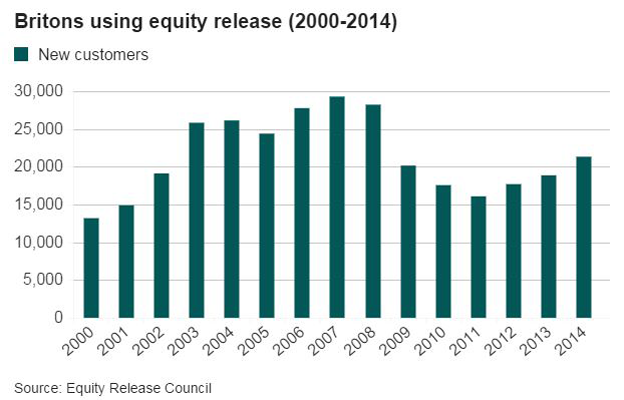

But if that is the true, why did only 21,000 UK homeowners take out equity release plans last year?

Given that 3.4m homeowners in England alone are between the ages of 65 and 74, that means that less than 0.5% of likely customers are currently signing up.

'Nothing left'

Here's the first problem: When you take out a lifetime mortgage, the interest rate you pay is higher than an ordinary residential mortgage.

The cheapest currently available is 5.4%, which is fixed for life.

But, also unlike a residential equivalent, lifetime mortgages involve compound interest.

So, assume your house is worth £300,000, and you take out £100,000 in an equity release plan, at the age of 60.

After year one, the amount you owe will be £105,400.

That sum will then be used as the baseline to calculate the following year's interest, and so on.

After 20 years -should you reach 80 - you will owe £286,293. True, the house may have gone up in value, but if not, you will have just £13,707 left to pass on.

Live just one year more, and you will have nothing left at all.

How compound interest eats your money

"People don't understand the way it builds up," says Merryn Somerset Webb, the editor in chief of Money Week.

"They find it very difficult to grasp the the concept of compound interest. It just needs to be clearer," she says.

The industry argues that lifetime mortgages are expensive, because providers are, in effect, making a triple bet: On house prices, interest rates, and how long you will live.

"We can't do anything about compound interest," says Nigel Waterson, chairman of the Equity Release Council, external.

"As Einstein said, it's the most powerful force on the planet." It's simply the cost of providing consumer protection, he says, such as guaranteeing that home-owners will not be responsible for any negative equity.

Case study

Those most likely to think of equity release as a dirty word are, of course, the children likely to be disinherited.

But if you have no one to pass your house on to, equity release could suit you perfectly.

Cyril and Jenny Barrett, from Oxfordshire, have no children, and didn't want the taxman to benefit from their death.

So in May this year they took out a lifetime mortgage on their £500,000 bungalow.

They are both in their late 60s. They decided to withdraw £158,000, to spend on a new kitchen, and a camper van.

"We have nobody to leave our house to. It's quite a problem for us actually," says Cyril.

Given their mortgage rate of 5.8%, they will owe their provider £501,766 in 20 years' time, more than the house is currently worth.

But any debt will be written off.

"It does seem too good to be true," says Jenny. "I'm waiting for the day they come and tell us something bad."

House prices

The companies who provide lifetime mortgages argue that the benefit homeowners are likely to get from rising prices will more than compensate for hefty charges.

"The rising value of their home can help offset the interest owed through equity release, which should ease fears that some have of eroding their housing equity," says Simon Chalk, of provider Age Partnership.

He advises those who want to pass money on to their children to take out no more than 20% of the equity.

Take someone whose house is worth £250,000, and who takes 20% in cash. Twelve years later, the amount they owe the lender will have doubled.

But assuming house prices rise at an annual rate of at least 2%, they will still own more than £200,000 of equity. This they can pass on, subject to Inheritance Tax.

Indeed part of the industry's argument - to be published in full next week - is that house prices are subject to the same compounding principle that applies to the charges - but this time to the benefit of home-owners.

'Safe'

Does all that mean equity release remains a dirty word?

"There's a gulf between the industry and the client that hasn't yet been bridged," says Merryn Somerset Webb.

But Nigel Waterson remains defensive.

"These days equity release is a safe and well-regulated product," he maintains.

In the months ahead the FCA will be examining how this market might be made to work more effectively.

But right now it's hard to imagine what new product might emerge, or whether this industry can silence its critics, permanently.