Fracking adversaries gear up for the next round

- Published

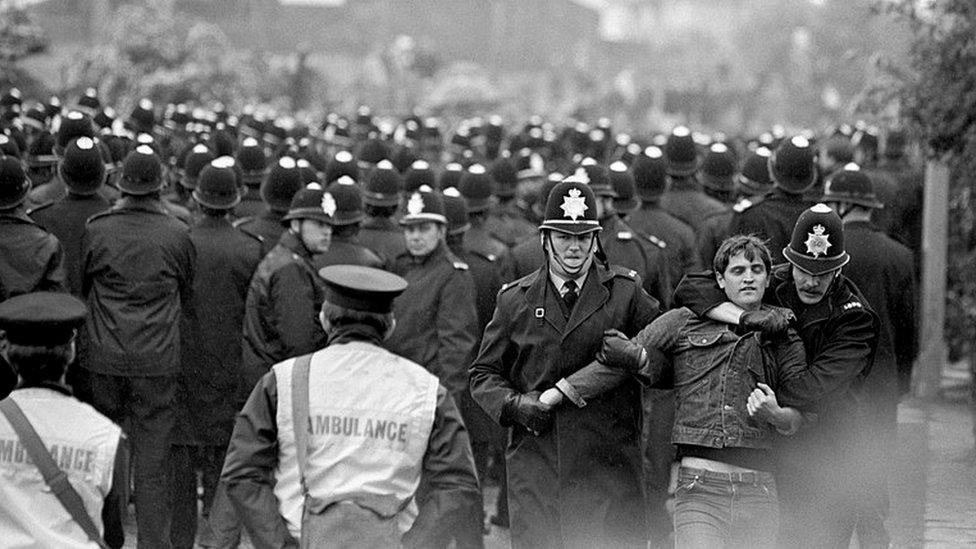

The miners' strike 1984: Could we really see similar bitter protests over fracking?

Lancashire County Council versus Downing Street hardly seems like a fair fight.

But these are the two protagonists in the next battle over fracking in the UK. There can only be one winner.

Earlier this year, councillors in Lancashire rejected Cuadrilla's application to drill a handful of shale gas exploratory wells. There would be too much noise and the impact on the landscape would be too great, they said.

The decision did not go down well in Downing Street.

For the Conservative government has made it abundantly clear it wants to see fracking in the UK as soon as possible - hence the raft of new licences issued on Thursday.

"Shale gas is a fantastic opportunity for the UK," says a Department of Energy and Climate Change (Decc) spokesman. By its reckoning, the industry could be worth billions of pounds, creating more than 60,000 jobs and increasing the UK's energy security.

Cuadrilla was fracking before a government moratorium was imposed in 2011

For this reason, the government will do everything it can to help clear the obstacles to widespread fracking.

It has already removed many. For example, if local councils take too long deciding on fracking applications such as Cuadrilla's, it will take the decision out of their hands after 16 weeks.

It has also changed the rules on property rights - fracking companies no longer need permission from landowners to drill horizontally deep underground. And just this week, ministers pushed through plans to allow fracking under national parks, external.

Perhaps most importantly, the government has decided to invoke long-held powers to decide planning appeals on matters deemed of national importance.

So Cuadrilla's appeal against Lancashire County Council's decision will not be decided by a planning inspector, but by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, Greg Clark.

No prizes for guessing which side he'll come down on, say environmentalists.

Fracking companies argue the disruption from drilling is not as great as many fear

No wonder energy expert Prof Paul Stevens at the Chatham House think tank says he's "quite sure central government will approve [Cuadrilla's application]".

Long road

But this doesn't mean we're about to see fracking wells springing up across the UK - far from it.

For a start, the planning process remains incredibly onerous. Cuadrilla, for example, first received a fracking licence in 2008 - those companies awarded licences later are just embarking on a very long and trying journey.

And even Cuadrilla still has a long way to go. If the company wins its appeal, as seems inevitable, there is still a huge amount of work to do.

The company will have to meet planning conditions and build the fracking site - by its own reckoning drilling could commence towards the end of next year, at best.

The BBC's David Shukman explains how fracking works

Then follows an extended period of what is known as flow testing, the results of which are unlikely to be known before 2018 - late 2017 at a pinch.

If the results are positive, then Cuadrilla needs to submit a planning application for commercial production, rather than exploratory drilling. This effectively means that "planning permissions and permitting have to be sought again," says Cuadrilla's chief executive Francis Egan.

This involves obtaining permits from a bewildering number of bodies, including the Environment Agency, the Mineral Planning Authority, the Health and Safety Executive, the Oil & Gas Authority and Decc.

If everything goes to plan, Mr Egan says "the likelihood is that commercial production would begin at the end of this decade".

The so-called dash for gas is clearly a complete misnomer.

Court referral

But planning is just one of many obstacles to fracking in the UK - even if all frackers gain all the necessary permits to drill, there is no guarantee we'll see meaningful amounts of shale gas production in the UK.

Proposals for fracking in the UK are deeply controversial for many

For a start, the economics of shale gas may not stack up given the low price of gas. In Europe, the gas price is linked to the oil price, and many experts believe the oil price will remain low for many years.

Meanwhile the question of property rights has not been fully resolved - associated horizontal drilling may be fine, but fracking companies still need permission from landowners to set up site.

If landowners don't agree, the government currently doesn't have the power to force them, although any stand-off "could be referred to the courts for a judge to decide", according to Decc.

Then there are questions about the geology itself.

The British Geological Survey (BGS) estimates there is about 1,400tn cubic feet of shale gas in the Bowland Basin in the north of England and the Midland valley in Scotland.

This is enough to meet UK gas demand for more than 400 years based on current consumption, but not all of it can be recovered.

In the US, recovery rates vary between 8% and 29%, but we simply don't know the equivalent figure for the UK, according to Ed Hough at the BGS.

Given that both the rock type and the depths at which the shale can be found are similar, frackers are understandably optimistic, but until multiple test wells have been sunk, no-one knows whether significant quantities of shale gas can be produced.

'Civil unrest'

But by far the biggest hurdle fracking companies must overcome is public opposition.

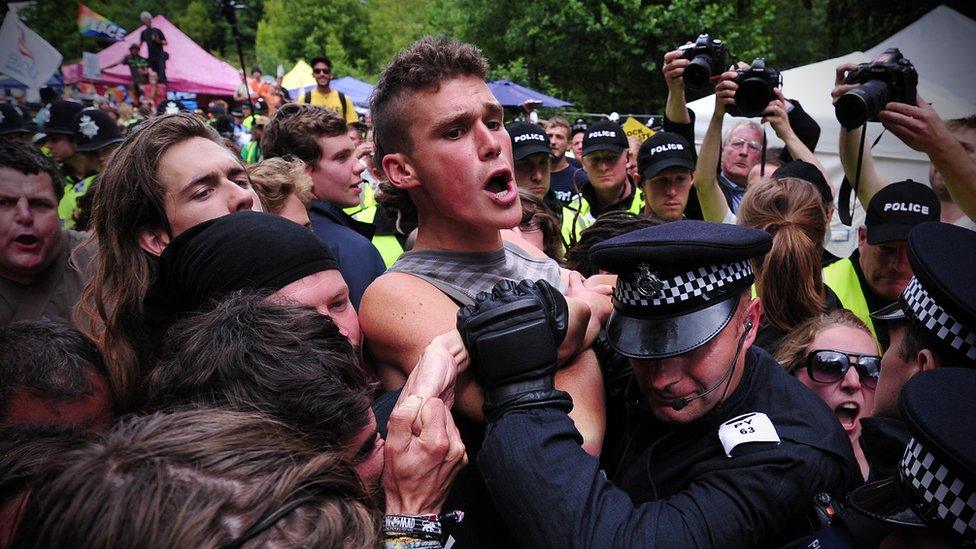

Police were called in to deal with protesters against fracking outside the village of Balcombe

We had a taster when protesters tried to stop Cuadrilla drilling a test site in the West Sussex village of Balcombe in 2013.

But we could be in for far worse, according to Prof Stevens, who argues that any government decision to over-rule local authorities would be "an absolute gift to the anti-shale lobby.

"It would make Balcombe look like a Sunday picnic. We could see serious civil disorder and unrest with troops [on the streets]. We're not talking Orgreave incident [levels], but not far off.

"The vehemence felt is so strong it would be virtually impossible to carry out sensible operations."

The ensuing chaos would, he argues, force other gas companies to question whether to proceed, meaning "to all intents and purposes, the shale gas revolution is dead".

Miners clashed with police at a Yorkshire coking plant at the Battle of Orgreave

The battle, during the miners' strike of 1984, was one of the bloodiest in UK industrial relations history

And he is not alone - the wider gas industry itself has said there will be no US-style revolution in Europe.

Perhaps most tellingly, some energy consultancies are no longer keeping a close eye on fracking.

"There is no interest in market forecasting as so many believe it is not going to happen," says John Williams at Poyry Management Consulting. The company's last report on fracking was in 2013.

"We could easily see no fracking at all in the UK."

So despite the best efforts of both the government and shale gas companies themselves, including the multitude of new licences being issued, fracking in the UK is far from a foregone conclusion.