Is India's airline sector set to take off?

- Published

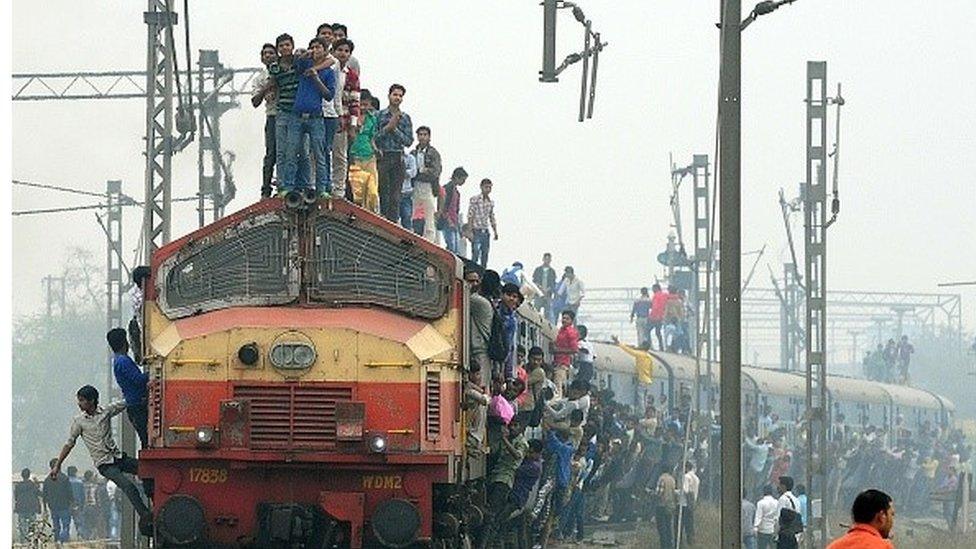

Trains are India's lifeblood - some 23 million people use the country's railways every day

To understand the potential of the aviation sector in India, you just have to make a trip to the New Delhi Railway station.

One of the busiest railway stations in the country, passengers line up in the hot sun for hours.

On platform number 14 the train arrives two hours before its scheduled departure, but that does not stop the mad clamour among passengers for a seat to get to their hometown.

People like 35-year-old Ravi Shanker Thakur say that taking a train is the only affordable way to see their relatives. Mr Thakur's family live faraway in Muzzafarpur, in the eastern state of Bihar.

By working in a Delhi factory, he saves 1,000 rupees (£9.90; $15) to make his annual trip home.

"I can't afford a flight ticket - I can barely afford a train ticket," he says.

"I wish I could travel in air conditioned comfort [on a plane], with a seat to sit on, but tickets are so expensive - I'll have to spend many months' salary to buy one."

Airport expansion

While the state-run rail network subsidises tickets to keep train travel affordable, many still aspire to fly.

But it is not just price that holds passengers back, it is also convenience. India's railway network reaches every state and territory across this vast country - there are 8,000 stations in total.

The Indian government plans to substantially increase the country's number of airports

Compare that with just over 100 civilian airports, and you can see that the geographical coverage of air travel is still fairly limited if you want to go further than a big town or city.

The government plans to change this though, aiming to build 200 more airports in the next 20 years.

And recent statistics show that the demand for air travel is growing strongly in the country.

Between April and June of this year, more than 20 million passengers flew within India, according to industry figures. That's up 19% from the same time a year ago.

Trains are the only way most people in India can afford to travel

Dinesh Keskar, senior vice-president of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, says that for the current financial year overall he expects 75 million passengers to fly in India.

And predicting that the number of Indian air passengers will only continue to grow, US-based Boeing expects a demand for 1,740 planes in India over the next 20 years, with an estimated total price tag of $240bn (£157bn).

Yet problems still remain in the aviation sector, such as the fact that many current airports are not always utilised after they were built in the wrong location - remote areas of the country where they struggle to secure enough passengers.

More than $50m has in fact been spent by the government in recent years on eight such airports that do not receive scheduled flights, and many more lie underused.

One such facility is Jaisalmer Airport, in India's north western state of Rajasthan. It cost $17m to build, yet has never opened.

And for India's airlines, most continue to lose money, blaming high operating costs - from airport charges to fuel bills.

Since 2009, Indian carriers including the state-owned Air India, and the now-grounded Kingfisher Airlines, have lost more than $10bn after years of below-cost ticket pricing and overambitious expansion. Kingfisher had its flying licence removed in 2013 after was hit by repeated strikes by staff who had not been paid.

According to the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation, airline debt stands at around $11.3bn, and rises to close to $14bn if liabilities to vendors are included. At an industry level, airline debt is now equivalent to more than 100% of airline revenue.

Falling fuel costs

However, the rising demand for air travel, combined with falling fuel prices, has started to make a positive difference.

Jet fuel prices have dropped by 41% in the past year, and with fuel accounting for a substantial portion of an airline's costs, most carriers have benefitted.

Indian airline Spicejet has staged a comeback after benefiting from a fall in jet fuel prices.

For the three months to the end of June airlines SpiceJet and Jet Airways posted an operating profit as against a loss in the year-ago quarter.

The big comeback story has been that of Spicejet. An airline that was perilously close to collapse at the end of last year.

It cancelled thousands of flights and was being denied fuel because of unpaid bills. Then its founder Ajay Singh - who had sold the company - came back to the business - promising to invest more than $200m and becoming the boss once more.

Mr Singh says India needs to change its mindset about aviation.

"In the past aviation was thought to be something that only the rich did," he says. "And because it was something for the rich, it was taxed much as colour television used to be in the old days, or like computers was taxed.

"Aviation is now something that is very much for the middle classes of India. If we can bring the cost down, you can help airlines bring down fares, you can stimulate the economy."

For now, everyone is betting on growing demand. Income levels are rising for many in the country, which might help turn around the fortunes of the industry here.

- Published21 September 2015

- Published8 April 2015

- Published26 February 2015