Brazilian farmers wake up to their own specialist coffee

- Published

Brazil is the world's largest producer of coffee beans

As soon as the sun rises in the Caparao Mountains in southeast Brazil, Tarcisio Lacerda takes me on a tour of his property.

We drive up the hills in his pickup truck to see farmers harvest the coffee beans in the vast valley around us.

Coffee has been the economic backbone of this region - on the border between the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais and Espirito Santo - for more than a century.

But after years of a commodity-fuelled boom, economies like Brazil are having a hard time adjusting to slower global demand and lower prices.

Over the decades, the Lacerda family has known fortune and poverty, with their wealth always oscillating around coffee. Droughts, government policies, global consumption, currency problems - these were blessings and curses that determined the fate of the Lacerdas.

But in the past five years, farmers in this region are finding new ways to make their own fortunes, trying to move away from producing cheap commodity beans and instead invest in top quality production.

Tarcisio drives me to the top of the hill and lets me in on their secret.

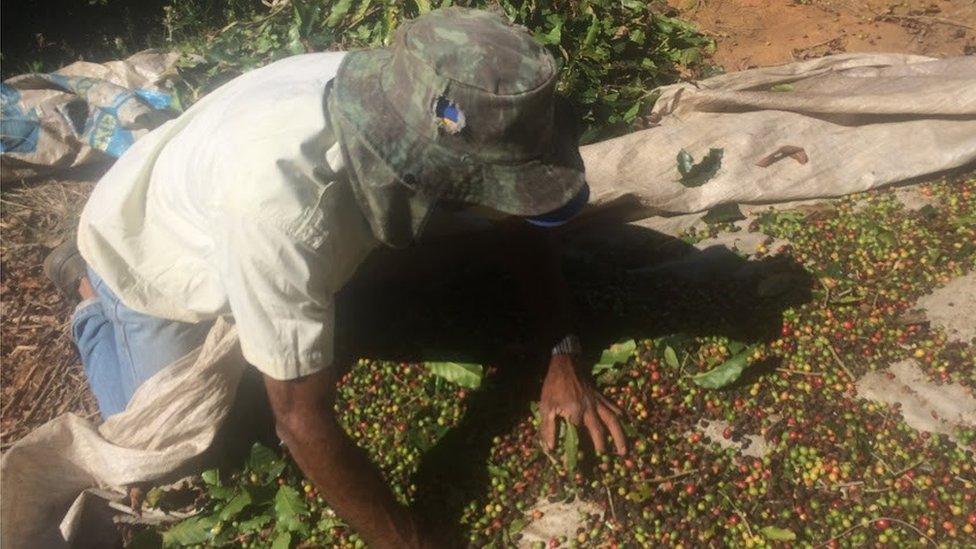

A worker collects coffee beans on the Lacerdas' farm

Specialty

The valley is filled with coffee trees - but not all of it produces particularly good coffee. In the past, farmers would collect all beans, put them in bags and ship them abroad, getting whatever prices were listed in the commodity markets.

Now Tarcisio and his family are separating the best beans - most of which are from trees 1,500 metres above sea level - and producing their own specialty brands. The rest is sold to the market as cheaper, unprocessed green beans.

Coffee farmer Jhone Lacerda advises regional coffee-makers on pricing and quality

"Usually you double your price - going from commodity to specialty," he says.

"A bag of commodity coffee is now worth 450 reais ($110; £72) - but we can sell specialty at around 900 or 1000 reais ($220 or $240)," he says.

Tarcisio takes me to his neighbour's farm - Forquilha do Rio - which has been winning some of Brazil's top awards for coffee.

Their quality has to do with the favourable local conditions - mild temperatures, good sun exposure and high altitude.

"We knew our coffee was good, but we had no idea it was this good," says Afonso de Abreu Lacerda (no relation to Tarcisio), in front of a cabinet packed with trophies.

"It wasn't until we started competing in awards, about five years ago, that we learned just how valuable it was," he adds.

In 2012, when Forquilha do Rio won one of Brazil's top awards, they were able to sell one of their lots for $950 - more than six times the commodity price at the time. They are now exporting their finished brand to China and Japan.

Young farmers' revolution

The "specialty revolution" is partly the brainchild of Tarcisio's son, 26-year-old Jhone.

When he was just 15, Jhone dropped out of school and moved into the family property, determined to learn everything about the coffee trade.

Brazil's premium coffee beans are attracting tourists to farm cafes

With each harvest, father and son experimented with different ways of harvesting, drying up and roasting their product.

Jhone designed, built and patented a new coffee drying equipment - which is one of the crucial elements of turning commodity beans into gourmet food.

He also became a licensed Q-Grader - a special category of coffee tasters.

They started developing their own brand - Fazenda Santa Rita - after buying roasters, and now have their own packages.

Market imposition

"This change in direction is something that the markets imposed on us," says Jhone Lacerda.

"We used to depend on the price of commodities - on things like how much coffee other countries are drinking, or whether they are in crisis or not," he tells me.

A growing number of Brazilian coffee growers are trying to take their crop upmarket

"We want to be in a smaller market, but that does not depend just on demand. In the specialty market, it is not the global demand that drives prices. It is the quality of the product that you put out."

Jhone uses his Q-Grader skills to advise all producers in the region on what price to charge for their harvests.

Together with two other families, he created the Montanhas do Caparao, a blend of some of the region's best coffees that has also won a top prize in Brazil.

Jhone is now back in school, studying coffee production at Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo college.

Going premium

Jhone's father tells me it took centuries for Brazil to finally wake up and smell its own specialty coffee. His parents had never thought of it before.

Brazil is the world's top producer and exporter of coffee by a large margin. It makes about a third of the world's coffee - but virtually all of it is green beans of very low aggregate value.

Brazilians don't export all their coffee

In the commodity market, the price for green coffee beans depends on factors such as climate and global consumption.

But other types of commodities - like soybeans and iron ore - are now suffering from the slowdown of the Chinese economy.

As Brazil and Latin America rely heavily on commodities and Chinese consumption, the whole region is slowing down to the tune of those markets. Brazil's economy is expected to contract more than 2% this year.

The head of the foreign relations department in Brazil's Ministry of Agriculture, Alberto Coelho Fonseca, says producers in many different areas are now trying to add value to food by exporting refined products, which is a way to compensate for lower international prices.

"A specialty coffee can be sold at 300% more value than a non-specialty coffee," he says.

"Even if they have a very small share in exports, the techniques of producing good specialty coffee can spread value through the chain."

Now some government officials want to help these premium brands take off abroad.

In next year's Rio Olympics, Brazil will serve its specialty coffee in tourism lounges in all venues.

Mr Fronseca adds: "About 70% of the coffee brewed by coffeehouses like Starbuck, Cafe Nero or Costa is likely to be from Brazil. We need to showcases our products better."

Tourism

Back in the Caparao Mountains, local producers found another way to add value to their product - tourism.

Local farms opened up special cafes and hostels, where visitors are taken on coffee-tasting tours, modelled on California's wine-producing Napa valley.

This is still in its infancy, but it helps consolidate the region's reputation for quality blends.

Now, say Jhone and Tarcisio Lacerda, half of the beans in their farms are already being used to produce their specialty roast, and they have big plans.

Jhone says: "We want to produce the best coffee in the world.

"We want the Caparao region to become well-known across the world."

- Published13 August 2015

- Published23 July 2015

- Published29 May 2015