Hong Kong minorities 'marginalised' in school

- Published

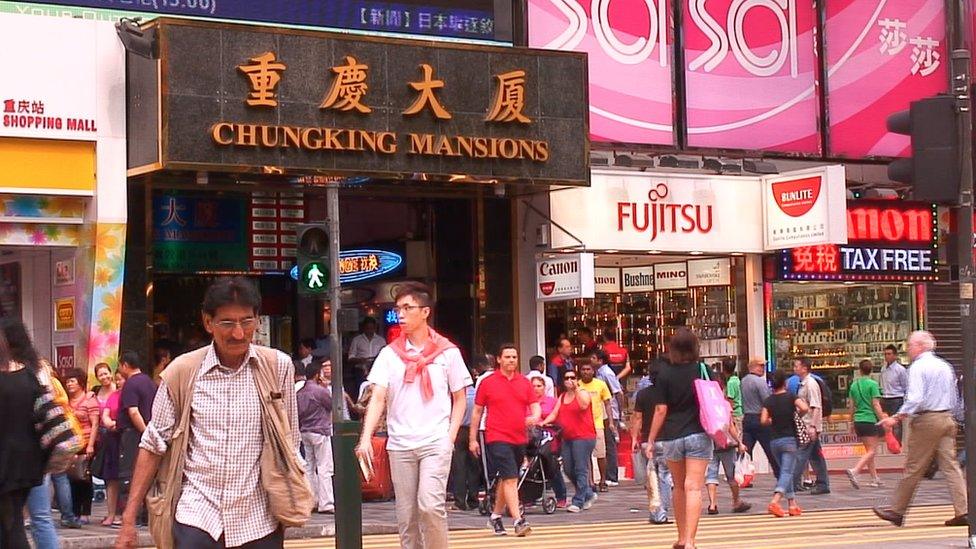

Hong Kong has many migrant communities - but do they get a fair chance in education?

Ethnic minorities in Hong Kong are "marginalised" by the education system, says a university study.

It found children of minority families do not get enough support to learn Cantonese - putting them behind in school and causing long-term problems in the jobs market.

"One of the main barriers to equal access has been a de facto racial segregation of ethnic minority students from Chinese students in the public school system," says University of Hong Kong law professor, Puja Kapai, who carried out the study.

The practice of communities studying separately has also meant that children grow up without interacting with other cultures.

Hong Kong is home to 365,000 ethnic minority people, making up 6% of its total population. Communities of Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalese and Filipinos have lived in Hong Kong for generations.

Hong Kong parents queuing to buy text books for the new school term

But the city still lacks a curriculum for children speaking Chinese as a second language, which would enable them to learn Cantonese, a requirement for many jobs and university places.

"The language requirement that forms a barrier for ethnic minorities to receive equal access in education and the labour market, can be seen as an indirect form of discrimination," says Raymond Ho, a senior member of the Equal Opportunities Commission in Hong Kong.

But he is confident that since the government made it unlawful to discriminate on the grounds of race in 2009, there is more public awareness of the needs of ethnic minorities.

More stories from the BBC's Knowledge economy series, external looking at education from a global perspective and how to get in touch

In the past there have been claims that Chinese locals are "less accepting" of people with darker skin. That was the claim of a report in 2008 from Unison, a group that campaigns for the rights of ethnic minorities.

This acceptance level was found to be lowest in the education sector.

Language barrier

Language is a major barrier for ethnic minorities to access education.

The best place to start learning Chinese and meeting people of other backgrounds is in kindergarten, says Holing Yip from Unison.

Language can be a major barrier to minorities in Hong Kong

But Unison's study Kindergarten Support Report 2015 showed that 62% of kindergartens used Cantonese exclusively as the interview language.

It also found that privately-run kindergartens were reluctant to give application forms to non-Chinese parents, and many ask children to have Chinese speaking skills by age three.

As a result, there is a concentration of ethnic minorities in a small number of kindergartens.

Mr Ho says the Equal Opportunities Commission has been "encouraging kindergartens to be open to ethnic minorities. But also not to use language ability as a selection criteria".

Divided schools

There has been a pattern of Chinese students enrolling in mainstream primary and secondary schools, where classes are taught in Cantonese.

Ethnic minorities would enrol in English-medium "designated schools".

Report author Puja Kapai says there has been segregation in schools

But the designated schools equipped students with such a low level of Cantonese that they would find it hard to enter university or employment.

As such some parents choose to send their children to Cantonese-medium schools.

"Having struggled themselves, many ethnic minority parents want their children to learn Cantonese so they don't go through what they did," says Ms Yip.

But getting information about how to apply to Chinese-medium schools is often only available in Chinese. Some have discouraged ethnic minority parents from applying.

Those who get places can struggle, as all classes are in Cantonese with no extra support in class and parents are unable to help at home.

Many parents are forced to seek extra tuition to help children with homework.

"There are situations where if a tutor can't come one day, their children won't be able to hand in their homework and will be penalised. It's also a huge financial burden," says Ms Yip.

Learning gap

Chinese University of Hong Kong student Deepen Nebhwani attended both types of schools.

"I learnt more Chinese in the mainstream school where all my friends were Chinese, just by practising it outside of class, than I did at the designated school where I studied Cantonese as a language class."

The pattern of separate schools for minorities put them at a long-term disadvantage, says study

After pressure from local non-governmental organisations and the United Nations, the Hong Kong government disbanded designated schools in 2013.

But the tendency to send ethnic minority children to particular schools continues.

"Ultimately, parents are faced with the decision of whether their children should suffer now in a Chinese-medium school, or later in the labour market. And that's not a fair choice for a parent to have to make," says Ms Yip.

Extra support

In September 2014, the Hong Kong government took a step forward by introducing a "learning framework" aimed at supporting ethnic minority students in learning Cantonese.

There have been migrant communities in Hong Kong for generations

Depending on the number of ethnic minority students enrolled, schools can receive from HK$800,000 (£68,000) to HK$1,500,000 to help them.

But Prof Kapai is sceptical about its effectiveness.

"It has simply broken the curriculum down into steps, but nothing has actually changed. There needs to be a Chinese as a second language curriculum to teach non-native speakers how to learn Cantonese properly," she says.

"Ethnic minorities may still be struggling with subjects such as maths as a result of the class and material being in Chinese," says Unison's Ms Yip

Limited options

Prof Kapai's report emphasises interlinked problems for minority groups.

A lack of Cantonese language skills will present barriers in employment, leading to an increase in poverty, and difficulty accessing healthcare.

The first day of term for pupils in Hong Kong

Cantonese language proficiency is a core requirement for some jobs, such as the civil service.

Typical occupations taken up by ethnic minorities are in the catering, construction and manual labour industries.

The Hong Kong Council of Social Welfare says that many Pakistani, Indonesian and Thai households are below the city's poverty rate.

"I identify as a Hongkonger," says Mr Nebhwani. But he is excluded from many jobs because of the limitations of his language skills.

"If I were to try and completely integrate, it would be hard because of my level of Cantonese."

"The government is committed to encouraging and supporting non-Chinese speaking students' integration into the community, including facilitating their early adaptation to the school education system and mastery of the Chinese language," said a spokesperson for Hong Kong's education bureau.