What's going on in UK manufacturing?

- Published

Manufacturing accounts for about 10% of the output of the UK economy

It's been a tough few weeks for the UK manufacturing sector.

SSI Steel has closed its blast furnace and coke ovens in Redcar, while Tata Steel has cut jobs at its sites in Scunthorpe and Lanarkshire.

Thousands of jobs are likely to go.

So what happened to the new dawn of foreign investment and the promised rebalancing of the UK economy towards manufacturing?

What state is UK manufacturing in?

The latest official figures on the manufacturing sector suggested, external that it had contracted 0.8% in August compared with the same month the previous year, although it had been slightly ahead of July 2015.

The CIPS Markit UK Manufacturing PMI, external survey suggested that September had also been a weak month for the sector.

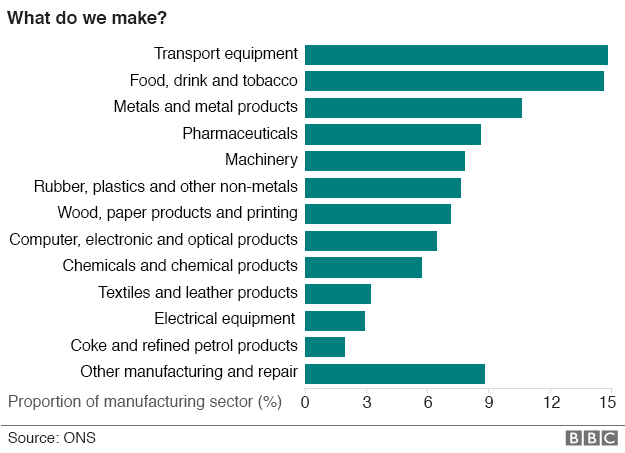

Manufacturing accounts for about 10% of the output of the UK economy.

The rest of the production industries: mining, quarrying, gas, electricity, water and sewage account for another 5%.

The service sector accounts for 79%, with construction making up the final 6%.

In the last decade, manufacturing grew gradually from 2005 to 2008, at which point it took a dive in the financial crisis in common with the rest of the economy.

It recovered from 2010 until the start of 2012 and has been pretty volatile since then.

The sector is still below its pre-crisis peaks, unlike the service sector, which is well above its pre-crisis level.

There was a line-up of British-built cars ahead of this year's Frankfurt Motor Show

Why have so many foreign companies invested in the UK?

Foreign investment plays a big role in UK manufacturing. There are lots of things about the UK that make it an attractive destination for foreign companies looking to acquire other businesses or expand overseas.

The UK is very open to other countries wanting to buy into it. It's within the European Union, which is attractive to US and Asian businesses wanting to reach European customers.

It has relatively low corporation tax and a flexible labour market, which makes it easier to expand and contract a business as is necessary.

Big holdings include Cadbury in the food and drink sector, which was bought by the US company Kraft. In the car industry, Nissan has factories in Sunderland. In the pharmaceutical industry, Pfizer has operations in the UK.

But in recent years there has been a big problem for foreign investors: the strength of sterling. A strong pound makes investing in the UK more expensive for foreign companies and it makes their products more expensive to export once they have been made.

What's been going wrong in the past few months?

There have been depressing headlines in the past few months about job losses and closures in UK manufacturing.

Rob Dobson, senior economist from Markit, which compiles a well-regarded survey of UK manufacturing, said the sector had been "stunned by a triple combination of a sharp slowdown in consumer spending, weak business investment and stagnating export order inflows".

But most of the big headlines have been about one sector: steel, with Thailand's SSI closing down in Redcar and India's Tata shedding jobs.

The industry in the UK blames this on relatively high electricity prices in the UK for such energy-intensive businesses, compounded by the extra cost of climate change policies.

It says that the government's policies to compensate steel companies for such extra costs have been coming in too slowly.

There are allegations that the Chinese steel industry has been selling steel in the UK at unrealistically low prices.

Also, the European Union is unusually strict about state aid to iron and steel companies. So it is a particularly difficult time for the UK steel sector, which is having an even harder time that manufacturing as a whole.

Is the manufacturing base fundamentally broken?

Many parts of the UK manufacturing sector have struggled to compete with lower-cost economies in Asia.

Most of the big headlines about job losses have been about one sector - steel

There is not much bulk production of toys in the UK, for example.

When big manufacturers shed jobs, many tend to go at once, often in parts of the country with relatively few alternative employers, which is why they make big headlines.

Industry bosses and unions say that the UK manufacturing sector could be stronger if the government was as much of a friend to industry as the governments of other EU members such as Germany and France.

"It is important that manufacturing exporters, in particular, get the support they need as they face significant challenges," says David Kern, chief economist at the British Chambers of Commerce.

"Additional efforts are needed on the part of the government to strengthen the manufacturing sector, particularly in key areas such as exports, access to finance and skills."

But there was one piece of good news for the sector in recent trade figures, which suggested an unexpectedly strong improvement in exports of goods and services, despite the strong pound.

"The cheering implication is that there has been more of a revival in the competitiveness of British manufacturing than other official statistics would indicate," BBC economics editor Robert Peston wrote.