Myanmar: The art of doing business in a country in transition

- Published

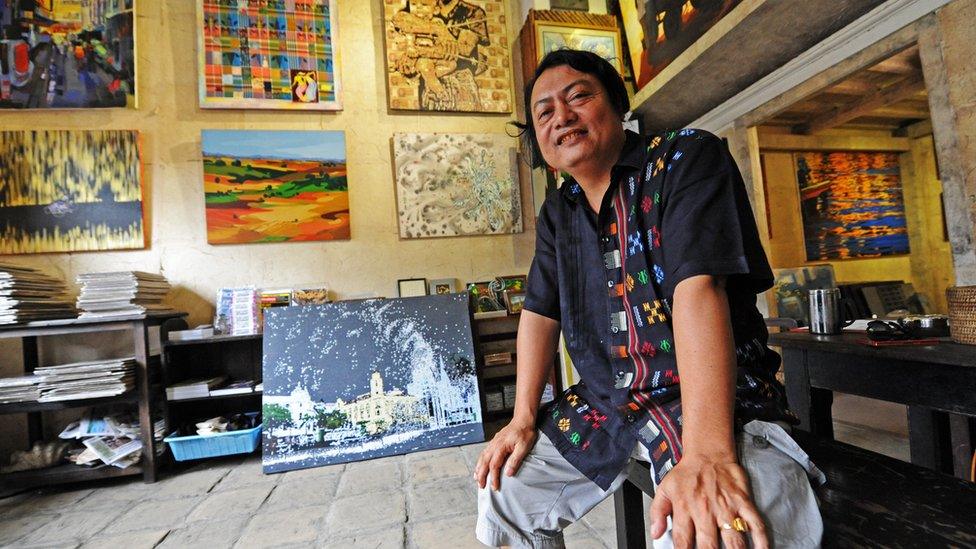

Demand for Burmese art from tourists and locals has pushed up prices

Leaving a half empty cup of tea on the table of his popular art studio in downtown Yangon, Aung Soe Min manoeuvres around a group of chatty local artists to greet a foreign couple, interested in purchasing paintings by local artists.

His Pansodan Gallery, which opened in 2008, is on one of the Yangon's busiest streets and as well as tourists, locals also flock there in ever greater numbers these days.

"This is the time for recovery from the stigma of the last 40 years of censorship," he says.

"For the artists, there is now more chance to earn an income, but it is also because they have more of a chance to be an artist."

Myanmar, also known as Burma, is approaching its first democratic election for 25 years, following decades of isolation. Over the last four years the government has relaxed rules on trade and investment and made it easier to do business. And the rapidly growing economy has given rise to a growing middle class.

Aung Soe Min points to several traditional landscapes and portraits as well as political works that were forbidden under six decades of harsh military rule. Prior to the reforms he says, exhibiting works depicting opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi could land you in jail, while a lack of clients led several struggling artists to other professions.

The cars on Yangon's streets are much newer models than they were a few years ago

And life is changing fast for Myanmar's middle classes

Now that the government has loosened restrictions on freedom of expression and tourism visas, both artists and gallery owners have huge potential to earn, he says. He is now preparing to open his third gallery.

Before, artists were earning less than $100 (£65) for a painting but are now getting five times more than that, as the number of buyers has soared. A few painters are now earning thousands for their work.

While much of Myanmar's economy remains dominated by the influence of the military and businesses with ties to the government, the growth of the country's middle class means new opportunities are opening up.

But Aung Soe Min says things remain quite chaotic.

"The artist cannot see that censorship is totally gone, and could still come back," he says.

Construction work is underway, transforming Myanmar's commercial capital, Yangon

Leaving Aung Soe Min's gallery and walking around the streets of central Yangon, it is clear that Myanmar's commercial capital is a city in transition.

Imported vehicles clutter the streets of colonial era downtown, driving beneath a mass of billboards, advertising luxury products and high-end real estate projects, bustling western-style restaurants and shops. Entrepreneurs, both local and foreign, are taking advantage of the new opportunities.

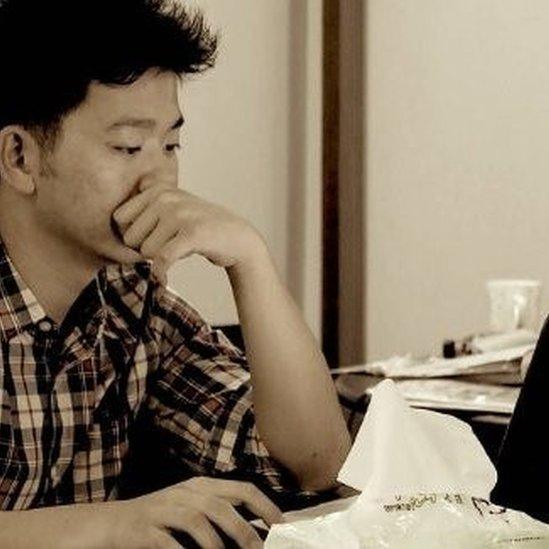

Khine Lin, a Burmese-American, was visiting Yangon, when he saw that the country's first hackathon was taking place - an event designed to encourage young Burmese to learn the basics of computer coding - not something any of them would learn in the country's still poorly funded education system.

He decided to sign up himself.

"I saw many other young people who are working on their own start-ups, contributing to the tech sector in Myanmar," he said. "I got really inspired. So, I decided to stay in Myanmar for good to get involved."

Lin started an online restaurant directory called MyLann that allows local restaurants to promote themselves to the country's growing base of restaurant-goers who are also online. The site now has more than 300,000 page views per month.

"Many new and diverse types of restaurants popped up," he says. "Internet speed has gotten significantly faster, including mobile internet and landlines. People, meanwhile, are getting more and more familiar with mobile technologies, apps and websites."

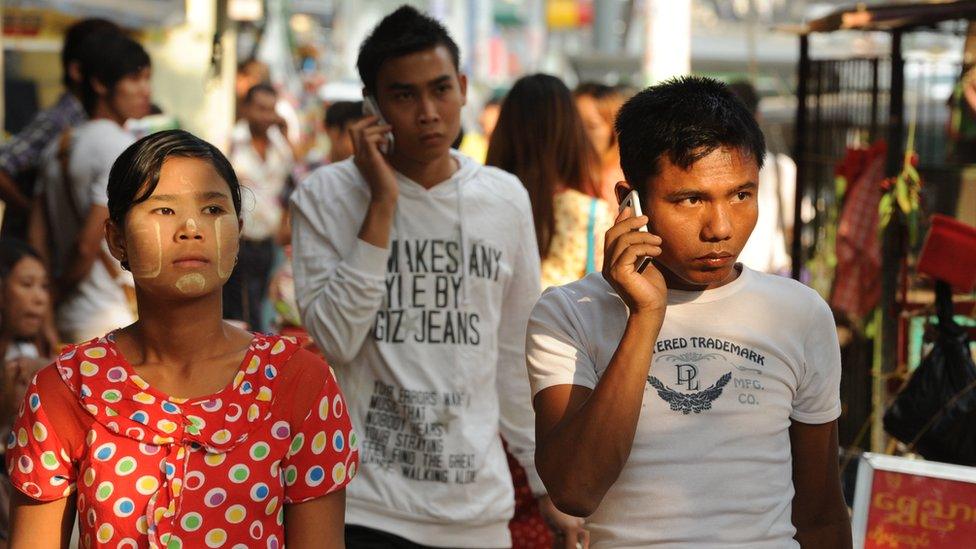

Six years ago mobile phone Sim cards cost hundreds of dollars, even up to $2,000 each. Now the price is just $1.50 and mobile phone penetration has spread like wildfire.

Khine Lin returned to Myanmar in 2014 to set up his own business

But the new opportunities notwithstanding, there are still challenges to doing business.

According to the World Bank, Myanmar is the 177th most difficult country in the world to do business in and the most difficult country in the world to start a business in.

Land and property are very expensive, and there's the issue of "tea money", the financial lubrication required to get official transactions completed on time.

But one key reform that has happened is last year's landmark issuance of nine banking licenses to foreign banks - making them the first foreign-owned banks allowed to operate in Myanmar.

For businessman, Thura Ko Ko, another returnee, reforming the financial sector is key to helping businesses run more smoothly and encouraging consumption.

He advises an American investment fund and has set up a chain of phone shops. He has just insisted on switching to pay his 80 employees by bank transfer instead of cash.

"There was a lot of resistance," he says. "Because they don't trust the banks yet."

"Now on payday they just take out their entire pay."

Debit and credit cards are still rare, people still pay for even large purchases like property and cars with cash, and bank services remain primitive.

In order to put a $20,000 cheque in his bank account recently Thura Ko Ko had to go to the issuing bank and withdraw the money in cash.

"We needed two pairs of hands to carry it. We had to wait half an hour for clerk to count it.

"Now my bank is closed I have to wait until Monday with this pile of cash in my house."

When the banks reopen he will have to go and physically pay the cash in, after it has been counted once again.

While reforms are beginning to be felt, particularly in Yangon and other big cities, the majority of the population is still rural. In many areas it's the boost to tourism that is bringing change.

Oliver E Soe Thet owns a small resort on Rakhine State's idyllic palm-lined Ngapali Beach.

Even though this is in a region troubled by ethnic conflict between Muslims and Buddhists, he says the number of restaurants on the beach front is set to triple to more than 150 next year.

But Mr Soe Thet says that while reforms have boosted local businesses, so has corruption - suggesting that developers have been known to pay off officials to acquire construction licenses for their hotel projects.

"There are no standards in construction and the existence of some buildings is highly illegal," he says.

But on balance he feels positive about the prospects for doing business.

"Many obstacles are gone," he says, especially the psychological barrier that stopped people travelling there. Now, he says: "Tourists and business people feel good about going to Myanmar."