Can making seawater drinkable quench the world's thirst?

- Published

The UN predicts that 1.9 billion people will live in "water-scarce" areas in 10 years

Producing fresh drinking water from the sea - desalination - has always seemed to be the most obvious answer to water shortages.

Our oceans cover more than 70% of the earth's surface and contain 97% of its water.

But the energy needed to achieve this seemingly simple process has been costly.

Now, thanks to new technologies, costs have been halved and huge desalination plants are opening around the world.

Big, bigger, biggest

The largest seawater desalination plant ever, Israel's Sorek plant near Tel Aviv, just ramped up to full production.

It will make 624 million litres of drinkable water daily, and sell 1,000 litres - equivalent to a Brit's weekly consumption - for 45p.

Nearby in Saudi Arabia, the Ras al-Khair plant reaches full production in December.

San Diego's Carlsbad desalination plant will be the largest in the US

Based in the peninsula's Eastern Province, it will be even bigger and will speed a billion litres a day to Riyadh, whose population is growing fast. A linked power plant will yield 2.4 million watts of electricity.

Then over in the US, San Diego's Carlsbad desalination plant - the country's largest - will be operational from November.

Clever membranes

The traditional way to extract drinking water from sea or brackish water is to boil it then collect the evaporated water as a pure distillate.

This uses a great deal of energy, but works well if combined with industrial plants that produce heat as a by-product.

Saudi Arabia's new desalination plant pairs with a power plant for this reason.

But reverse osmosis - a technology that has been around since the 1960s - uses less energy and has been given a new lease of life in recent years.

Saudi Arabia's Ras al-Khair plant will produce a billion litres of drinking water a day

This involves pushing salt water at high pressure through a polymer membrane containing holes about a fifth of a nanometre in size. A nanometre is a billionth of a metre. The holes are small enough to block the salt molecules but big enough to allow the water molecules through.

"This membrane strips all the salts and minerals completely from the water," explains Professor Nidal Hilal at Swansea University, editor-in-chief of the journal, Desalination.

"You have clean water coming down as permeate, the concentrate on the other side is brine, with high salt content."

But these membranes could get easily clogged and lose performance.

Now, better materials technology and pre-treatment techniques keep them working more efficiently for longer.

Israel's Sorek plant uses double-sized pressure vessels to process more water with less energy

And in Israel, Sorek's designers saved energy by using double-sized pressure vessels.

"You then need fewer pressure vessels to generate the water, meaning fewer pipes and fewer connections," says Dr Jack Gilron, head of Desalination and Water Treatment at Ben Gurion University.

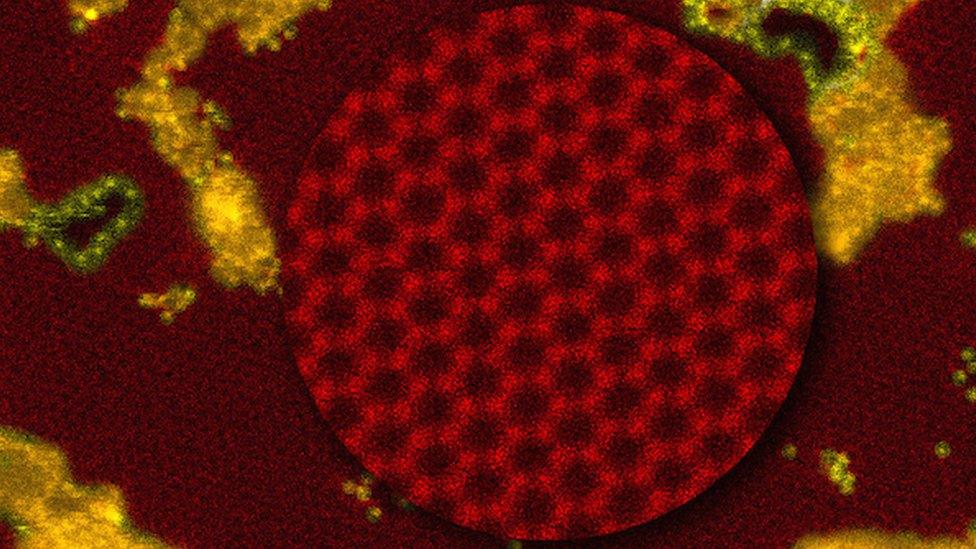

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US have even experimented with semi-permeable membranes made from atom-thick graphene.

These should need a lot less pressure to work, thereby saving energy, although the technology is not ready for mass production yet.

Alternative tech

Forward osmosis, according to Professor Nick Hankins, chemical engineer at the University of Oxford, is an alternative way to remove the salt from seawater.

Rather than pushing the fresh water through the membrane, a highly concentrated solution is used to draw it through, effectively sucking it from the sea water.

Afterwards you remove the diluted solutes, yielding pure water.

"If you design your draw solution in a very clever way, it can be possible to separate water out with very little energy," he says.

Researchers at MIT are experimenting with atom-thick graphene membranes (in red)

Another potential method is capacitive deionisation - essentially a magnet for salt.

Dr Michael Stadermann of California's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, believes "we should be able to do brackish water desalination at between half and a fifth of the energy of reverse osmosis".

That's if the technology makes it out of the laboratory.

Over salted?

One issue with desalination is what to do with the leftover salt.

Water in the Persian Gulf historically was 35,000 parts per million (ppm) salt. But according to the United Arab Emirates' Ministry of Environment and Water, some areas nearest desalination plants now measure 50,000ppm.

"You have to make sure the very salty water is pushed away far enough into the sea that you don't have recirculation of the water, because otherwise it will be getting saltier and saltier," says Floris van Straaten of Finnish engineering company Poyry, the firm overseeing construction of the Ras al-Khair project.

If water becomes too salty, as in the Dead Sea, few living things can survive

Jessica Jones from Poseidon Water, the firm building California's Carlsbad Desalination Plant, says: "Our plant is co-located with a power plant which uses sea water for cooling. Our discharge gets blended in, so by the time it goes into the ocean, the salt has been dispersed."

But US environmental groups have fought construction of new desalination plants in the courts, saying the consequences of reintroducing brine to the ocean have not been adequately studied.

"And when water is being drawn from the ocean, it brings fish and other organisms into the machinery - and that has an environmental and economic impact," says Wenonah Hauter, head of Food and Water Watch in Washington DC.

Pricey water

Desalination may be getting cheaper but it is still prohibitively expensive for poorer countries, many of whom also suffer from water scarcity.

More than two-fifths of Africa's 800 million people live in "water-stressed" areas, defined as providing less than 1,700 cubic metres of water per person, taking the needs of industry and agriculture into account as well.

Transporting fresh water from coasts to arid inland areas is another challenge

And the United Nations predicts that in 10 years 1.9 billion people will live in water-scarce areas - struggling on less than 1,000 cubic metres of water each.

What water-stressed regions most need is a desalination device than can supply 100 to 200 people - the size of a village.

Capacitive desalination is one potential solution, as is solar-powered desalination, with costs reducing threefold in 15 years.

So while desalination has gone big in wealthier countries, it also needs to go small to benefit those unlucky enough to be poor in both money and water.