Will digital tech tear up the paper concert ticket?

- Published

Can our phones beat the ticket tout?

You can check in at the airport and the cinema using a smartphone these days, but live music gigs have stubbornly clung on to the paper ticket.

More than 140 million tickets to live music events are sold each year, according to music listings site Pollstar, in an industry worth more than $10bn (£6.5bn).

And the vast majority of these will be physical print-outs, even if they are bought online.

But two UK start-ups are hoping to bring gigs screaming and kicking into the paperless age.

Mobile music

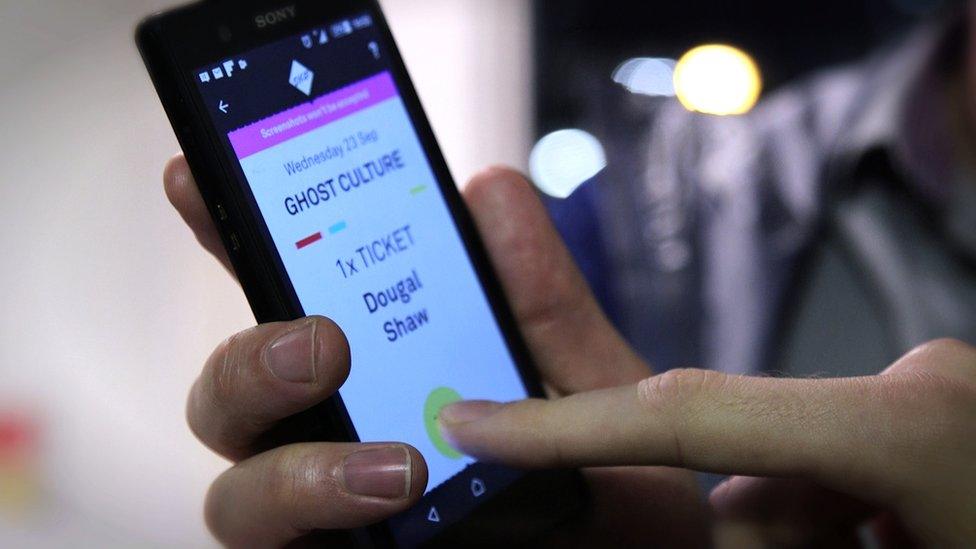

One of them, Dice, has developed a free app that allows users to browse upcoming gigs from a curated list. When you buy a ticket it is stored in a virtual wallet on your phone.

For smaller gigs, your name on an animated strip is enough to gain entrance. For larger gigs, you'll get a unique QR (Quick Response) code that can be scanned quickly by a reader.

Dice sends its own representatives with a bespoke app for reading the QR codes - and emergency phone chargers.

An animated stripe on the digital ticket stops counterfeiters using a screengrab image

"If I was going to see the Rolling Stones at Hyde Park then maybe I'd want to keep the ticket, but not tonight," confides one dedicated live music fan before a Ghost Culture gig.

He got into the Corsica Studios venue in south London by simply flashing an app on his phone to the man on the door.

"Young people don't have printers, they don't have email addresses, to print a ticket is a huge hassle for them," shouts Jen Long, music editor at Dice, as the support act warms up behind her.

"Everyone just does everything on their phone."

That's the ticket

Una, another music ticket start-up, is taking a different approach.

It provides users with a plastic membership card with embedded chips, to be scanned at venues. The card works in conjunction with a user's online account and can also be used for cashless payments.

Una offers members a plastic card to use instead of paper tickets

"If you are selling tickets for a major event like Glastonbury or Wembley you can't expect everyone to have Android or iOS," says Amar Chauhan of Una Tickets, which will launch in November.

Una members pay a small membership charge, then a standard booking fee per ticket in return for the convenience of paperless, hassle-free gig-going.

Members can transfer tickets to other members, but only at their face value.

Dice is trying to win market share by selling tickets at face value with no booking fee on top. It hopes to make money from merchandising and "added value" services.

Tackling the touts

Dice and Una believe their digital ticketing systems can defeat the endemic - and perfectly legal - practice of ticket touting.

Traditionally this involves men with booming voices outside gigs offering to buy or sell tickets at more than their face value. Often, these tickets are fake.

There's also a thriving secondary market online, with sites like Stubhub (owned by eBay); Viagogo; Seatwave and GetMeIn (both owned by Ticketmaster), dominating the scene.

There are even software bots that "scrape" ticketing sites, snapping up tickets as soon as they are released.

This means many places at concerts are left unfilled - with true fans priced out.

The government is currently reviewing the secondary ticketing market, external, following this year's Consumer Rights Act.

Not coming in

These start-ups may have developed innovative technology, but can they get it past the door?

There is a huge obstacle in their way, and it's called Ticketmaster, the largest ticket seller in the world. It is owned by Live Nation, one of the world's biggest music concert and festival operators.

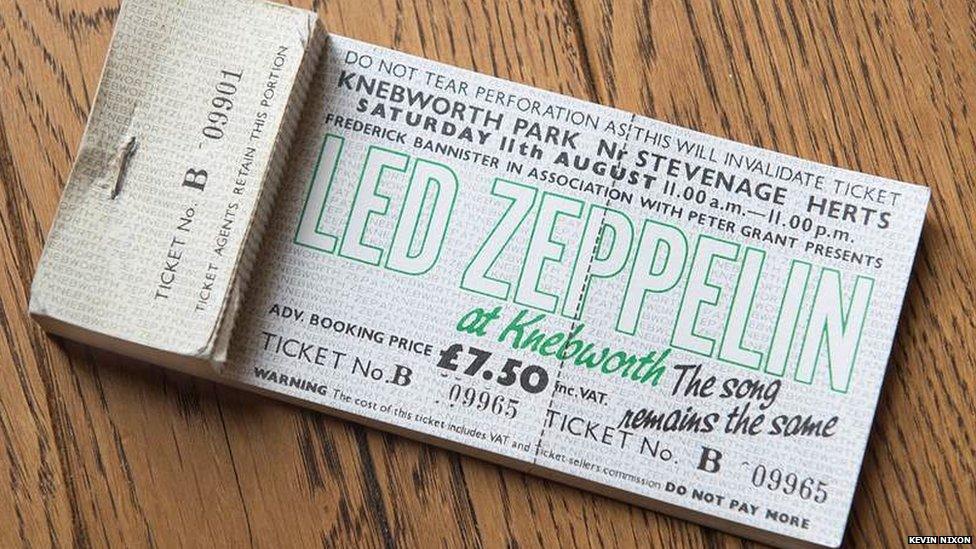

Rock concerts and paper tickets have always gone hand in hand

Many large venues have contracts with Ticketmaster, meaning they must sell an agreed allocation of tickets through the operator.

And these venues operate a barcode system owned by Ticketmaster.

Songkick - a successful digital start-up that began as an alert system for fans about upcoming gigs, but now sells tickets, too - works within the constraints of the Ticketmaster system.

Checking into a gig is not like checking into a flight, explains Songkick's co-founder, Ian Hogarth.

"I've worked on the door and it's a question of scale. You don't want people fiddling on their phones. When you've got thousands of people trying to get into a venue in the space of an hour, a paper ticket is crude but efficient.

"Any mobile technology needs to do at least as well."

Dice has to send a representative to work alongside the venue's usual ticket staff

There is an industry-standard technology for flight check-ins, he adds - something the live music industry lacks.

The BBC wanted to talk to Ticketmaster UK about its vision for smartphone ticketing, but the firm declined to contribute.

Striking it rich?

With such a powerful incumbent dominating the market, do Una and Dice really stand a chance?

Nearly 27 million tickets are sold annually for live music events in the UK, generating £1.3bn, according to the latest figures from UK Music and Oxford Economics.

So perhaps a tiny slice of a big pie is still worth having.

Will the song remain the same when it comes to the ticketing industry, or can it embrace mobile technology?

But some observers remain sceptical that mobile ticketing is about to sweep the industry. After all, just 28% of gig-goers used smartphones to purchase tickets last year, according to a poll by Mintel.

This might suggest relatively few of us are ready to switch to mobile-only tickets just yet.

"Nobody is brave enough to make mobile the only way to get into a gig so far," says Chris Cooke, business editor of industry newsletter, Complete Music Update.

"Companies like Dice and Una are primarily pitching to the grassroots and early adopters at the moment."

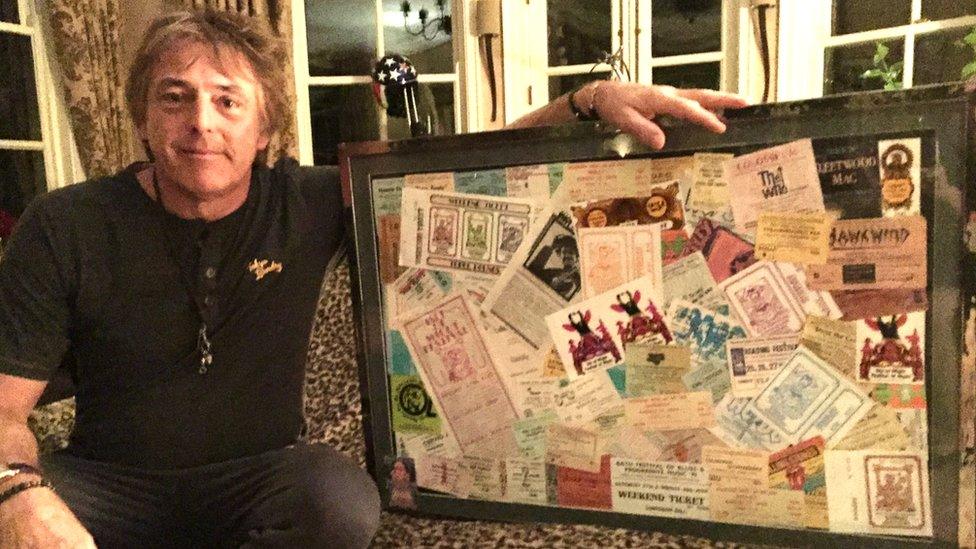

Collector Peter Ellis has over 600 paper concert tickets from his favoured 1966-74 period

The paper ticket, it seems, still has a powerful hold over us.

"There is nothing that can evoke such a sense of nostalgia as the feel, the touch and even the smell of an aged ticket with its creases, tears, stains and fading," says music memorabilia connoisseur, Peter Ellis, who has been collecting paper tickets for most of his adult life.

"It is a fond and permanent memento of a special, intimate and shared memory."

Providers of digital gig tickets have their work cut out.

Follow Dougal Shaw, external and Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall, external on Twitter.