Can tax credit cuts be made less painful?

- Published

- comments

When Gordon Brown and his then adviser Ed Balls embarked on their reshaping of the British welfare state by massively increasing benefits delivered to lower-paid, working people through the tax credit system, one of their aims was cynically political.

The more people who received these credits, and the more generous they became, the more frightened those on average or lower incomes would be of voting Tory.

Or, as they told me, so Brown and Balls hoped.

Well in the end the bribe didn't work.

In fact, Labour lost office in 2010 at a time when tax credits were costing the public sector far more than they had ever done - because incomes were so flattened by the 2008 financial and economic crisis that the top-up from tax credits rose very significantly.

So, according to the Treasury, when the modern system of tax credits began properly in 2001-2, they were costing the Exchequer the equivalent of just over 0.8% of GDP or national income.

But by 2010, the real cost of this system of subsidising work had more than doubled, to over 1.8% of GDP.

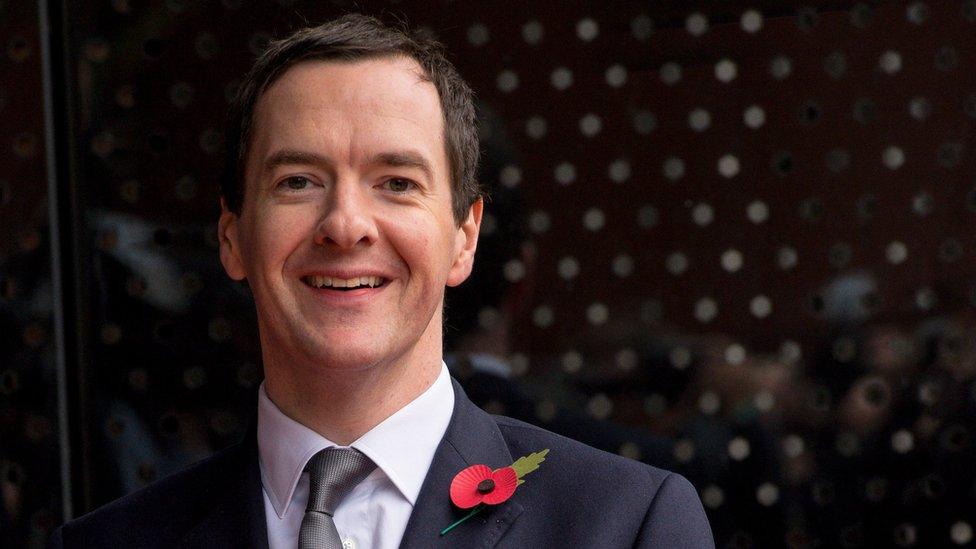

No surprise therefore that a Conservative Chancellor, George Osborne - for all his commitment to encouraging work - should view this state subsidy as excessive.

But it is quite important to note that, for all the outrage of his planned cuts to tax credits, they will still cost the government 1.2% of GDP by the end of this parliament - or a full 50% more in real terms than when they were properly launched by Brown and Balls.

So why all the fuss - especially at a time when even the Labour Party concedes that the government continues to borrow too much?

Work instead of benefits

Well there is one big reason.

To state the obvious, George Osborne is taking quite a lot of money almost immediately (well next year) from a lot of poor people, most of whom are doing what would be widely seen as the right thing by working rather than choosing to live on benefits.

The available numbers on this are by no means scientifically precise.

But the House of Commons Library says that for 3.28 million in-work families, of which 2.7 million have children, the average loss will be £1,300 (and the Institute for Fiscal Studies would broadly corroborate).

Now, the vast majority of these earn less than £20,000, so the sudden loss of spending power for this group is very significant indeed. A 10% loss of real earnings would not be untypical.

Taper rate

There are a number of other points of significance here.

One is that, of the four elements of tax credit changes, the second biggest short-term contributor to savings for the government - yielding £1.5bn next years - is an increase from 41% to 48% in the so-called "taper" rate at which the tax credits are taken away after a recipient's income reaches a particular threshold.

In a way, that can be seen as a marginal rate of tax on additional income earned by those on low incomes: for every additional pound earned, 48p less of tax credits is received.

What is striking is that 48% is higher than the top 45% rate of tax for those earning more than £150,000.

And to many, including Tories, who worry about worsening inequalities, the symbolism of a taper rate for the poor higher than the top rate of tax looks unnecessarily inflammatory.

Taking money away

What is also striking is that George Osborne is doing something that chancellors only rarely do, which is that he is actually taking money away from people, rather than reforming the system so that it only affects new claimants.

Or to be more precise, the two biggest elements of the reforms - reducing the thresholds so that maximum payments are withdrawn at a lower income level, and increasing the taper rate - affect all claimants (the removal of the family element in tax credits and limiting the child top-up to two children bite only for new claimants).

He would argue that, for many, the loss of earnings will be offset by the way he is forcing employers to pay their staff more, by pushing up the minimum wage - renamed as the living wage - well above its past trend, and also by boosting the zero income-tax threshold.

But this compensation will be only gradual and - as the IFS has calculated - will not provide 100% restitution to all.

Also, even if he were to cut national insurance payments for those on low earnings - as he is said to be considering - he could not be confident that there would not still be big losses for significant numbers of poor workers.

New claimants

All of which points to the biggest oddity of the reforms.

George Osborne could have made them much less contentious if all four elements applied only to new claimants.

Of course, the yield to the Exchequer would have been significantly less for two or three years.

But, because the earnings of many of today's claimants will in time rise above the maximum threshold, the long-term savings would have been almost identical to the current proposal.

Or to put it another way, the government's deficit would be reduced at a slower rate; there would have been £3bn or £4bn less of a reduction for the next couple of years, but thereafter the pace of deficit squeeze would have accelerated.

Here are the questions that presumably are whizzing round George Osborne's brain.

Is the political embarrassment for him of a slower rate of deficit erosion worth the opprobrium being flung at him, even by some on his own side, for cutting the earnings of what his party like to call lower-paid "strivers"?

And, at a time when the Labour Party has moved to the left, is it politically astute or cack-handed of him, as a contender to succeed David Cameron as Tory leader and prime minister, to be positioning himself on the hard-nosed right in this manifestation of his approach to reforming the welfare state?

George Osborne is certainly as political a chancellor as Gordon Brown was when he invented the modern system of tax credits. He will therefore be deeply concerned that he is self-harming in his remaking of that system.

Would it be political shame or glory for him to recast the reform by inserting the word "new" before "claimant" for all elements of the tax-credit reconstruction?