Why is hi-tech Japan using cassette tapes and faxes?

- Published

Japan loves its robots but still uses faxes in the office

Japan has a reputation for being fascinated by robots and hi-tech gadgets - a nation at the forefront of manufacturing innovation.

But the technological reality in many offices is strikingly different.

This is a country that uses people to do the work of traffic lights and where big-name companies running 10-year-old software is the norm.

There are even tape cassettes for sale in the ubiquitous convenience stores for office use, along with fax machines - remember them? Even tech visionaries like Sony still use a fax.

"Japanese companies generally lag foreign companies by roughly five-to-10 years in adoption of modern IT practices, particularly those specific to the software industry," says Patrick McKenzie, boss of Starfighter, a software company with operations in Tokyo and Chicago.

"The pace of development is glacial."

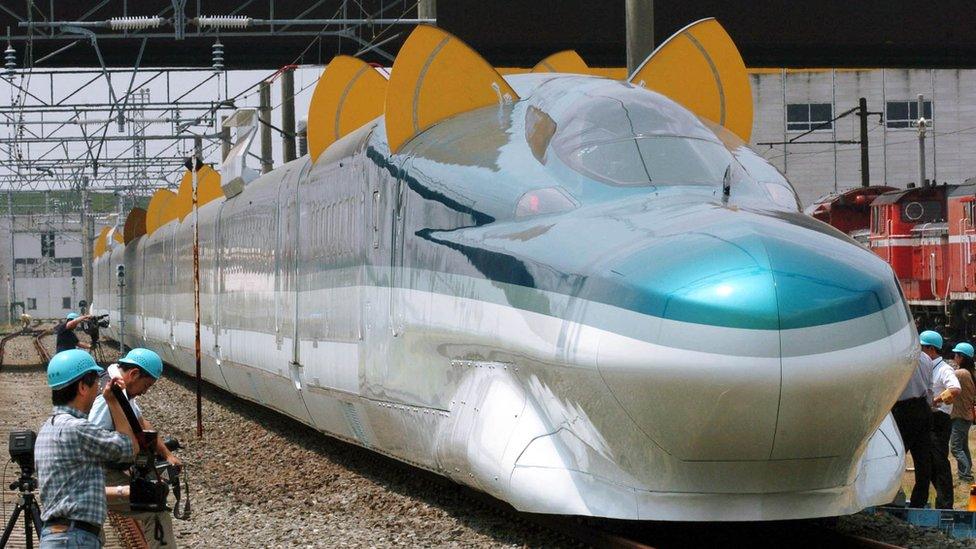

Japan invented the high-speed bullet train but still uses human traffic lights

It's a curiosity for any observer of a country that developed the world's first contactless payments system; the Bullet train; and the Sony Walkman.

You can pay for things with your phone in Japan, but nobody really uses their e-wallets here; ditto for Skype in the office, or other now-ubiquitous cloud storage tools, such as Dropbox.

Yet Japan has some of the best internet infrastructure in the world.

Hand-written faxes

Yoji Otokozawa, president of Tokyo-based IT consultants Interarrows, says Japan Inc. is poor in digital literacy because small businesses, not multinationals, rule the country.

"You have to understand how SMEs [small and medium-sized enterprises] dominate the Japanese business landscape," he says.

SMEs account for 99.7% of Japan's 4.2 million companies, according to Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. So the world's third biggest economy is driven by minor establishments, not the giants everybody knows outside of Japan.

Yamaha is developing a robot that can ride a racing motorcycle

These SMEs are often conservative, if not downright Luddite, says Mr Otokozawa.

"They usually use postal mail, or fax for their communications. We sometimes receive a fax, written by hand which means such firms don't even use word processing software like Word."

Bureaucratic

But even some bigger, modern global firms seem mired in digital backwardness, although finding people willing to go on the record about the phenomenon is difficult in a culture where devotion to one's employer is the norm.

"Eventually you accept that a company whose pride is its cutting-edge tech image makes employees use an email service that looks circa 1997," goes a recent anonymous tweet from an employee of a well-known blue chip Japanese technology firm.

Mariko Oi reports on Japan's quest to rediscover the Walkman ethos

Speaking to the BBC on grounds of anonymity the tweeter - Twitter handle The Hopeful Monster - revealed more about his company's paradoxical attitude towards office technology.

"For email and internal communication we used Cyboz, which was text-only, and we were allowed a minuscule amount of server space, so deleting and/or transferring old emails because your allotted space was full was a near-monthly activity."

The vast majority of firms in Japan are small enterprises, not tech giants

Burning data onto discs and delivering them through the post, accompanied by a data submission form "filled out by hand," was encouraged by managers.

And when software updates or the adoption of collaborative tools like Basecamp and Dropbox were suggested, management spurned them, he maintains.

An "overzealous approach to problem prevention was typically to forbid new software from being installed," he adds.

'Remorselessly conservative'

If such alleged behaviour is typical, it could explain Japanese firms' productivity crisis, says Rochelle Kopp, founder of Japan Intercultural Consulting, an international training and consulting firm focused on Japanese business.

With one foot in Tokyo and another in Silicon Valley, she says: "US workers are much more productive because they have access to the best technology - the US is at the technological frontier."

Cassette tapes, obsolete technology in many countries, are still sold in Japanese shops...

Japan's failure to ditch its analogue habits and go digital means its "companies are losing out on productivity boosters," says Ms Kopp, who used to work in a large Japanese firm for several years.

"Japanese IT departments are remorselessly conservative and hate to connect their computers to the outside world. They fear data theft and hacking, which also makes them fear abroad."

One female office worker in a global logistics company in Tokyo - again speaking on condition of anonymity - says: "Japanese hesitate to use anything new in the office."

...and human traffic lights still regulate the roads

She says the attitude tends to be "vincible ignorance" - what Aldous Huxley described as "not knowing because we don't want to".

Consequently, Japan's non-manufacturing productivity, despite the long hours worked, is the worst in the OECD countries and roughly half that of the US.

Humans not robots

As Martin Ford, author of Rise of the Robots points out, the more advanced your IT, the more likely it is to replace you.

So despite the tech-loving public image, much of corporate Japan seems intent on circling the wagons against automation and using people rather than machines wherever possible. After all, those faxes don't pick up themselves.

Serial start-up businessman William Saito is on a mission to make Japan more entrepreneurial

Such overstaffing may help keep the country's unemployment rate down at 3.4%, but it also keeps productivity down, too - not to mention entrepreneurialism.

Whether such an approach can stave off the rise of artificial intelligence, robots and automation in a world moving from a commodity-based economy to one based on intellectual capital, seems unlikely.

But corporate Japan seems intent on trying.