Training India's millions of unskilled workers

- Published

Mahendra says he has never received any training

On a Monday morning outside a suburban train station in Mumbai, Mahendra Singh Shekhawat is looking to get a job for the day.

He is one of hundreds of labourers who are waiting in small groups for contractors to come and give them jobs at construction sites. He works as a helper to a ceramic tile-setter, making just $6 (£4) a day.

"I have never received any training; there is no one to guide us. We just see and learn while we are on the job," he says.

"If I get some skills in civil construction, then I will start earning more, my work will be more stable and I will have a secure future - but we don't know who can help us.''

Mahendra is typical of millions of Indians who form more than 90% of the country's unskilled and semi-skilled workforce. Most of them have little or no formal training.

Outdated studies

To meet the challenge of helping Mahendra and those like him - and cut youth unemployment, which is currently 12.9% - Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government recently launched its Skill India Mission.

In the programme's first year, the government aims to provide skills to 2.4 million young people.

Student Pratima Jain is worried that what's she's being taught may be outdated

A few kilometres away from the workers is Pratima Jain, 22, who is studying pharmacy and management at the Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies (NMIMS) in Mumbai.

But even though she's in full-time education, she is concerned her curriculum may be outdated.

''Educational reforms and the upgrades have a pace much slower than the industry growth and change in technology," she told the BBC's Talking Business.

"In most colleges, there is a lack of communication between the students and professionals from their industry.

"As a student, it would help in making decisions of a career easier... [if] you are aware of exact pathways successful people in industry have followed."

'We are not doing enough'

Mumbai jobseeker: 'We were never made aware of getting training in our job'

Indian employers often complain about a lack of skilled workers, which means they have to invest time, money and effort in on-the-job training.

"There are a lot of people like us who want to hire workers, but we don't find the right candidates," says Vandan Shah, managing director of Sipra Engineers.

His firm has three plants in Maharashtra producing car parts and industrial components, employing more than 500 employees with a turnover of $18m.

"There a lot of people waiting to get jobs, but they are not skilled," he says.

''I don't think we as industry are doing enough to train our workforce - so that's a change that's got to develop.''

"What we find is that young graduates, especially engineers, want to get ahead fast without getting their hands blackened on the shop floor. This leads to them switching jobs quickly. It is very crucial for them to have the right attitude.''

He says India needs more vocational training centres, as well as investment from industry, government and academic institutions, to make higher education more market-oriented.

There is often a mismatch between firms' expectations and would-be recruits' talents, says Purvi Seth

Purvi Seth, the boss of Shilputsi, a Mumbai-based HR consultancy, says there is often a mismatch between what companies expect and the existing pool of talent in the labour market.

"And they both don't always meet," she says.

''It is the responsibility of companies as well as individuals to improve skills gap," she says.

"It is important for individuals to know where their skills will be redundant, and organisations need to do more cross-functional training and encourage job rotation.''

Unemployability or unemployment?

India faces several different labour market issues, says Ninad Karpe, chief executive of the IT training firm Aptech - unemployment, unemployability and the problem of too many people.

"All of it cannot be solved at the same time, but if we have to look at one of the three, then unemployability can be tackled first.''

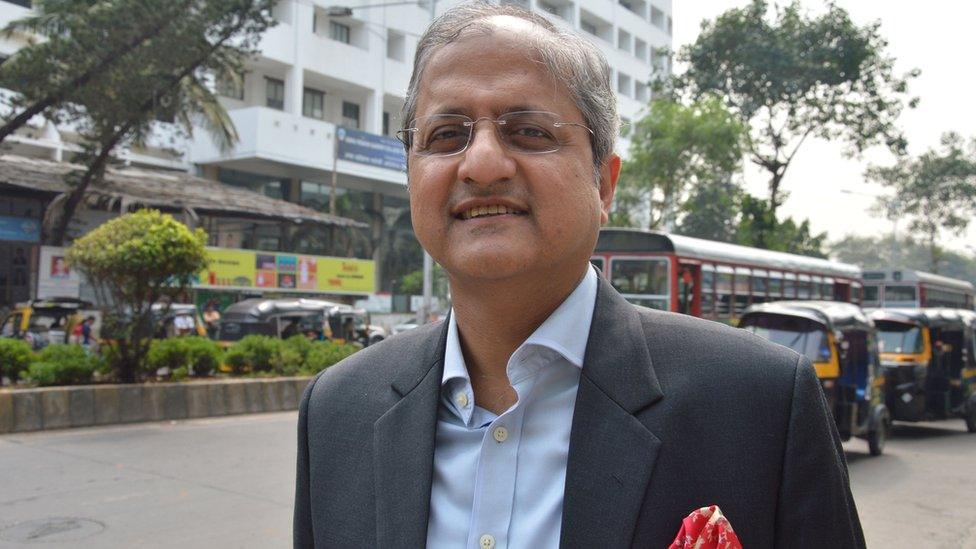

Indian businesses need to set up more internships, says Ninad Karpe

Mr Karpe's firm has trained more than seven million students worldwide. He agrees that one of the underlying causes of India's skills shortage is the quality of its educational system.

One solution, he says, is for industry to engage more with academic institutions and to set up more internships.

"In many countries, students do some level of vocational training and internships. The percentage of students doing this in India is in single digits.''

Wider risks

It is a big problem. According to government figures, fewer than 5% of India's 487 million workers have received any formal skills training. In other industrialised countries, that figure is closer to 60%.

With the launch of its Skill India Mission, the government says it aims to give people practical vocational skills and better qualifications, backed up with financial rewards for those who complete their training.

The government wants to equip more than 400 million Indians with practical skills by 2022

''The challenge is around implementation and quality of training. As long as there are measures to keep both at the highest levels, it will be an excellent source of well-trained talent," says Shilputsi's Ms Seth.

Despite the skills mismatch, many young Indians have high hopes of success after finishing further education and are becoming entrepreneurs, setting up their own tech companies. According to the Ministry of Finance, this is transforming India into the world's fourth-largest hub for start-ups,

Aptech's Ninad Karpe warns that the problems India faces could eventually threaten its economic performance.

''If we are unable to match the aspirations of young Indians, we will be failing in our duty," he says, meaning that India's firms "will not get the best talent".

"Companies should create an environment which bridges the gap between aspirations and reality.''

You can see more on this topic on this week's episode of Talking Business. The programme is broadcast on the BBC News Channel on Saturdays at 20:30 BST, and on BBC World on Fridays at 14:30 GMT, Saturdays at 00:30 GMT and on Sundays at 12:30 and 18:30 GMT.

- Published8 July 2015

- Published24 June 2015