Tonga facing up to rising sea levels

- Published

Climate conference: The view from Tonga

The vulnerability of the Kingdom of Tonga to any rise in sea level is starkly evident from the moment your plane begins its descent.

From the air, the flat, small island of Tongatapu doesn't look much like land at all, with the astonishingly blue Pacific Ocean dominating the view.

But it is home to Tonga's capital, Nuku'alofa, and to the majority of the country's population - 70,000 or so out of around 90,000.

And for Tongans, who have lived here since the 9th Century BC, when the first settlers arrived by boat, the issue of rising sea levels and climate change is not just one for discussion at an abstract level - it proves a threat to their very existence.

Tonga's economy is weak - based to a large extent on remittances from expatriates, and on foreign aid.

Agriculture is mainly at subsistence level, and fishing - which is done by traditional spear - has lost some popularity over the previous decades, as cheap imported off-cuts of meats have replaced much of the traditional diet.

Highly religious, and well educated, Tongans' attachment to their fragile land is something evident in their pride and discussion of traditions and culture.

'Fighting the inevitable'

Tourism is barely visible on Tongatapu, where most land is owned by the King and the nobility (33 families).

Foreign investment is not much in evidence either; though what is evident is that many people from Tonga's 150 outer islands, which scatter over hundreds of miles of sea, are relocating to the main island as their own fragile habitats face an uncertain future.

Most Tongans live on the coast

These are often in informal settlements, which can suffer from a lack of infrastructure, and some of which are in tsunami "red zones".

Yet at Fafa Island Resort, a tiny, picture-perfect island merely 20 minutes by boat from Nuku'alofa, tourists enjoy the luxury of sleeping in a traditional Polynesian hut - right by the beach. Or they do - for now.

Vincent Morrish, who manages the hotel with his wife, points out the erosion that will mean the huts will eventually have to be moved back into the centre of the island.

"We're already having to move the restaurant and bar area back," he says, pointing out at what was once the beach, but is now between 5-10m (16-32ft) out to sea.

"We're fighting the inevitable," he adds, as he walks around the makeshift defences the resort has put in place to hold back the increasingly fierce tides.

When asked if in 100 years the island will still exist, he replies: "Absolutely not". And the tourists? It's a question not answered.

Mr Morrish says the kitchen was rebuilt further back from the water a year ago, and they'll be shutting in February to relocate the restaurant and the decking - otherwise, their guests will be dining in the water before too long.

Coping mechanism

Living by the sea is a proud part of Tongan culture and identity, with 80% of Tongans living right on the coast.

Yet rising tides and increasingly unpredictable weather is making life difficult.

Many roads in Tonga are washed away by rising tides

Siale 'Ilolahia, the executive director of the Civil Society Forum of Tonga, a local non-government organisation, visits a road near the capital, where a coastal community with little infrastructure exists.

"This road was washed away by the rising tides," she says. "We rebuilt it but it's going again."

The road is a thin strip of land separating a small swamp where mangroves have been washed away - leaving the land unprotected from winter cyclones - and a lagoon leading to the vast Pacific.

It is a stunning spot. A short distance from the road is a tiny speck of an island - just one tree remains.

She looks troubled as she points it out: "People used to fish from there - they used it as a base. It was a [proper] island not long ago."

The families dotted along this coast have few sources of income - and many still fish for their food - with spears - as they have done for millennia.

Do they fear the rising seas? Not necessarily, she says.

"Many people just accept changes here - nature changes - it is just part of life and they don't really have much choice.

"There are cyclones, there is a rising sea - but for many of us, getting on with life as normal is a way of not accepting the problem - and just coping."

But a problem it is.

'Extinct culture'

Sione Fulivai is Tonga's senior climate finance analyst. He is in no doubt that the problem of small island economies vulnerable to changes in climate is urgent, and that the rest of the world is duty-bound to pay attention.

He is in Paris - along with many other pacific island states - at this week's UN climate change talks, where a legally binding agreement on carbon emissions is sought. What will he be asking?

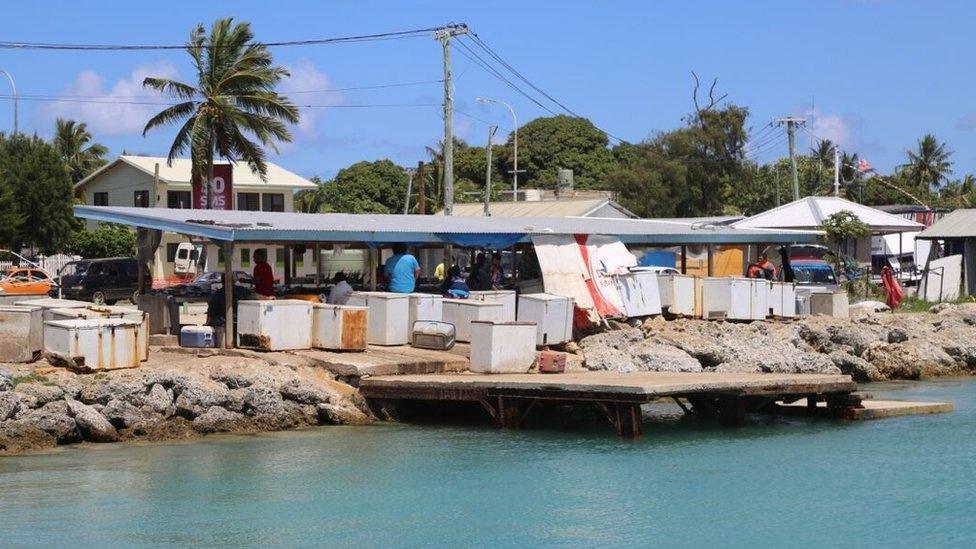

Sea defences are being built across the islands

"A lot of countries and governments are in Paris negotiating their economies - we're just asking for survival," he says.

"We don't want to become another extinct culture."

Does Mr Fulivai feel dwarfed by the size and might of other global economies on this issue?

"We're fighting against the dollar, against the pound… we are tiny - we haven't got the size or the money - but we are suffering the most."

What about relocation? Something often talked about with small island communities. Relocation has already taken place within Tonga across its string of small islands.

Mr Fulivai is firm - relocating Tonga is unthinkable, and besides, where would the whole population of over 90,000 relocate to?

The nearest land is Samoa, Fiji and New Zealand. He says none of these are viable options.

"Where would we go? We are tied to our land - to our culture," he says. "Without our lands who are we?"

- Published23 August 2023

- Published4 July 2015