Companies still bending finance rules, Enron boss warns

- Published

Enron's collapse in 2001 was the biggest in US corporate history

The convicted former finance chief of Enron, the failed US energy giant, has sounded a warning about corporate fraud, saying companies now have even more scope to bend the rules than when he was at the firm.

Andrew Fastow said the tools that companies used to manipulate their financial reports were even "more potent" today.

He pleaded guilty to two counts of securities fraud in 2004 and was sentenced to six years in jail for his role in Enron's collapse. Its bankruptcy in 2001 was the largest in US history.

Enron went from being the seventh-biggest company in the US to folding in the space of just four months, putting 21,000 people out of work and sparking a landmark crackdown on corporate accounting.

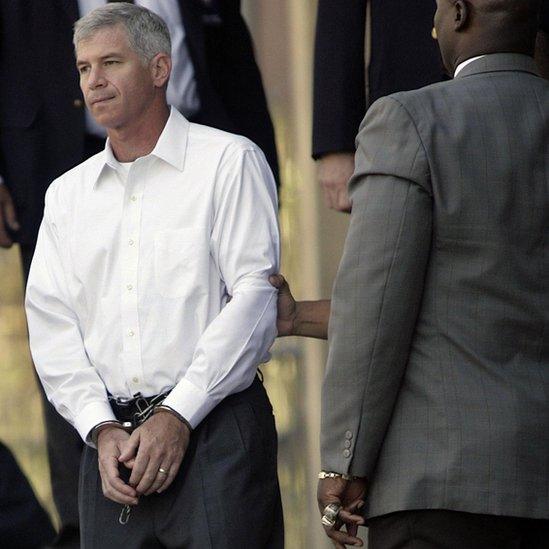

Andrew Festow arrives at court in 2006 for sentencing for his role in the Enron collapse

Mr Fastow admits to creating the structured finance transactions that kept debts off of Enron's balance sheets, and made the company appear to be in better financial health than it really was.

"It is easy to find examples of companies causing misrepresentations while following the rules, and they're using those tools to do it," he told the BBC after speaking at a conference organised by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) in Singapore this week.

"Most companies do not do it to the extent that I did it at Enron, so they don't suffer the consequences like we suffered, but companies do it to varying degrees."

Mr Fastow's 10-year prison sentence was reduced after he testified against former Enron chief executives Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling, who were also convicted for their roles in the firm's demise.

He was released in 2011 and now works at a law firm in Houston advising clients on potentially damaging accounting and financial issues.

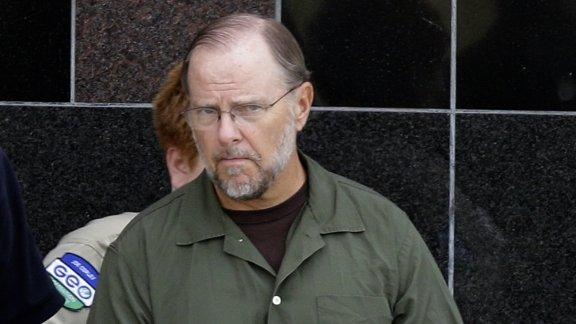

Former Enron boss Jeffery Skilling (left) was sentenced to 24 years in prison

'Grey area' of accounting

Mr Fastow said unclear accounting rules allowed companies to abide by the rules but also misrepresent the financial state of their business at the same time.

"Accounting isn't straightforward - 10% is black and white and 90% is in the grey area," he said. "When you're in the business world, being ethical is a lot harder than you think."

By pointing out the loopholes used by other firms, Mr Fastow stressed that he was not trying to excuse his actions at Enron.

"What I did was wrong and it was illegal and for that I'm very sorry, very remorseful - I wish I could undo it," he said. "But I'm trying to explain how someone who didn't necessarily set out to commit fraud or do harm, could come to do that and on such a grand scale."

Calling himself the "chief loophole officer", Mr Fastow said that every deal he did at Enron was approved by its board of directors.

"You can follow all the rules and still commit fraud and that's what I did at Enron," he said. "Follow the rules - but undermine the principle of the rule by finding the loophole."

The transactions Mr Fastow used to conceal costs from Enron's financial statements, known as "operating leases", remains the most common form of structured finance in the US.

"There are over $1tn (£658bn) off-the-balance-sheet operating leases in the US," he claimed.

Andrew Fastow after being sentenced for his role in the collapse of Enron

'Loophole industry'

Despite laws being passed and greater scrutiny of corporate balance sheets since Enron collapsed and the financial crisis struck, Mr Fastow said he did not believe that companies were becoming more honest.

"There's an industry of accountants, attorneys, consultants, and bankers that do nothing except figure out ways to get around the rules, to find loopholes," he said.

"By the time a new rule or regulation is codified, the bankers, accountants, attorneys and consultants have figured out ways to structure around those rules."

Hedge funds and private equity firms still called him for advice on what loopholes different companies were using, along with short-sellers who wanted to capitalise on firms that might have hidden troubles.

Executives now need to consider the ethical implications of deals and the risks they might pose for the company - something Mr Fastow said he never considered at Enron.

"My mistake was that the only filter I used to make my decisions was whether or not I was following the rules," he said. "The filter I should have been using once I learned that I'm following the rules, was whether it is ethical and whether or not the decisions are presenting an acceptable amount of risk to the company."

Employees with their belongings after Enron collapsed in December 2001

'Questions that need asking'

If he had his time at Enron over, Mr Fastow said he would not do deals he knew were 'wrong'.

"I was doing deals that were intentionally misleading, that didn't have an economic benefit and there's no other way to say it, but that's criminal," he said. "I didn't think of it as criminal at that time, but it is criminal."

Since being released from prison four years ago, Mr Fastow has also been teaching courses at the University of Colorado and giving speeches to students, business and auditor groups.

His motive is to make people ask more questions, he explained. "I don't give answers, but what I hope people take away is that there's questions that we need to be asking that we're not asking - the type of questions I didn't ask myself."

- Published21 June 2013

- Published2 February 2014

- Published19 October 2015