Harvard students take pledge not to cheat

- Published

Harvard, with a motto "veritas", meaning truth, is making its students take a pledge of honesty

Students at Harvard this term have been doing something for the first time in the university's long history.

Promising not to cheat.

Or more specifically, to sign up to an honour code - or "honor code" in the US spelling - in which they pledge to uphold values of academic integrity.

It means students at the prestigious US university have to commit themselves not to cheat in exams, make up figures or dishonestly claim other people's work as their own.

It's not just a one-off promise.

Students will reaffirm the honour code before taking exams

Brett Flehinger, Harvard's associate dean of academic integrity and student conduct, says students now write their own "personal response" to the pledge before starting term, reaffirm their commitment when registering and then again before taking exams.

Cultural change

The message is about "changing the culture", says Dr Flehinger, with a more overt assertion of the principles of academic honesty, rather than just chasing grades.

"Students are under a lot of pressure, not all of it healthy," he says. And the honour code is meant to re-balance this.

"What we're trying to say to students is that accuracy and honesty are the foundation of all academic work and knowledge, scientific, humanities and social sciences," says Dr Flehinger.

The Harvard College Honor Code

Members of the Harvard College community commit themselves to producing academic work of integrity - that is, work that adheres to the scholarly and intellectual standards of accurate attribution of sources, appropriate collection and use of data, and transparent acknowledgement of the contribution of others to their ideas, discoveries, interpretations, and conclusions.

Cheating on exams or problem sets, plagiarising or misrepresenting the ideas or language of someone else as one's own, falsifying data, or any other instance of academic dishonesty violates the standards of our community, as well as the standards of the wider world of learning and affairs.

Harvard's adoption of an honour code follows a high-profile cheating scandal in 2012. On one exam paper, more than a hundred students were investigated and about 70 subsequently faced sanctions.

What really rocked this institution was the scale. For a university used to coming top of global rankings, which had taught eight US presidents, it was a deeply uncomfortable question mark over its reputation.

The adoption of an honour code, already used by many other US universities, sends a message to new arrivals that the whole ethos of attending Harvard should be about honest endeavour.

More stories from the BBC's Knowledge economy series, external looking at education from a global perspective and how to get in touch

But what are the beliefs of Harvard's students?

In terms of moral, political and sexual attitudes, there must be more known about Harvard's annual intake than any other university's.

An annual survey by the student newspaper, the Harvard Crimson, goes into remarkably granular detail:

almost two-thirds of students start Harvard as virgins

more than a third have not drunk alcohol

about a quarter have tried cannabis, a much higher proportion than smoke tobacco

nearly two-thirds have a religious belief

most consider themselves politically liberal

almost one in five have had mental health counselling

80% arrive on campus with an iPhone

Cheating arts

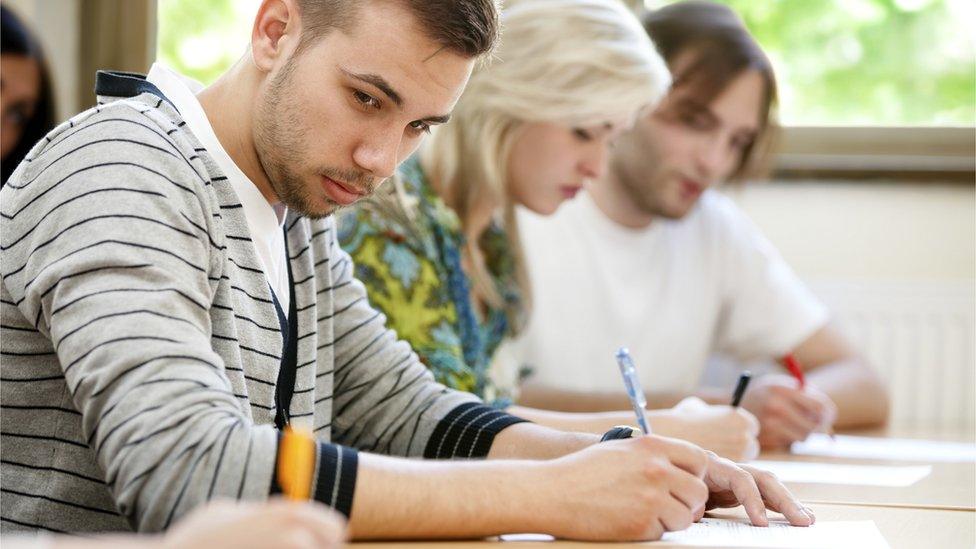

But the survey, based on a sample of more than 70% of new students, also asked about cheating.

It found 9% admitted to having cheated in an exam, a figure consistent with previous years. There were others who had cheated on homework, assignments and other types of assessed work.

Randomising the seating arrangements for exams reduced cheating, say researchers

The survey found 23% of the students admitted to cheating in academic work before starting at Harvard.

So will students be deterred from cheating by a promise?

A study published in October by the US National Bureau of Economic Research suggests a persistent underlying level of cheating.

Ming-Jen Lin, from the National Taiwan University, and Stephen D Levitt, from the University of Chicago (and co-author of the best-selling Freakanomics), looked at science exams taken at an undisclosed "top American university".

This found "compelling evidence" of cheating from at least 10% of students. The type of evidence included candidates sitting near each other handing in exactly the same wrong answer.

This 10% level of cheating is consistent with other wider surveys, say the researchers.

"It is not surprising that students cheat - they have strong incentives to do so, and the likelihood of getting caught is low," concluded the study.

"What is perhaps more surprising, is that so little effort is devoted to catching cheating students."

Moving the chairs

Prof Levitt's study suggests cheats were often sharing information with someone else at the next desk.

And the researchers were able to experiment with a very low-tech response.

Sir Cary Cooper says he doubts an honour code will stop cheating

At short notice, they randomised the exam room seating to stop people knowing whom they would be near, and as a result "almost all evidence of cheating disappears".

Would an honour code make a difference?

Sir Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology and health at Manchester Business School, says: "I don't think it actually stops the cheating that much.

"A university will have it because it gives explicit ethical and moral guidance about what is inappropriate behaviour."

If anything goes wrong, and there is a cheating scandal, he says, it means universities can say they provided clear evidence about the rules.

It limits reputational damage - and the risk of law cases from students - rather than creates an "institutional value system", says Sir Cary.

But he also says that cheating has changed - with the internet opening up new uncertainties about copying and sharing - and that students themselves might not recognise their actions as dishonest.

This includes those high-flyers expecting to do "exceptionally well", he says. They will "rationalise" that "there's nothing wrong with it" that it is only what other students are doing.

"There are some people who are so motivated to do well, they will cross the line."