Is China a brake on Africa's progress?

- Published

Chinese traders have opened up businesses across Africa

China's economy is slowing down - but are there any other economic casualties?

The short answer is: "Yes." Africa has been adversely affected, although not so much as to snuff out the real improvement over the past two decades.

Economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa is, according to IMF projections, slowing to 3.8% this year, external, the slowest since 1999. Slower, in other words than during the global financial crisis.

That projection, released in October, is also down from the 4.4% the IMF published just three months earlier.

It is still, however, faster than the increase in population. So economic activity per person, which is a rough, if flawed indicator of average living standards, is still rising.

In all but 10 of the 45 individual African countries, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is likely to rise this year.

And next year, the IMF forecasts, Africa will regain a bit more momentum, with growth of 4.3%.

The state-run China Daily launched an African edition in 2012, highlighting China's growing presence in Africa

In the 11 years after the turn of the century, the economy of sub-Saharan Africa doubled in size.

In 1993, GDP per person was about the same as in 1970. By 2010, it was 50% higher.

China was an important factor, though it can't claim all the credit. There were real improvements in political stability and economic policy in Africa, although some analysis, external suggests progress in this area may have stalled since the financial crisis.

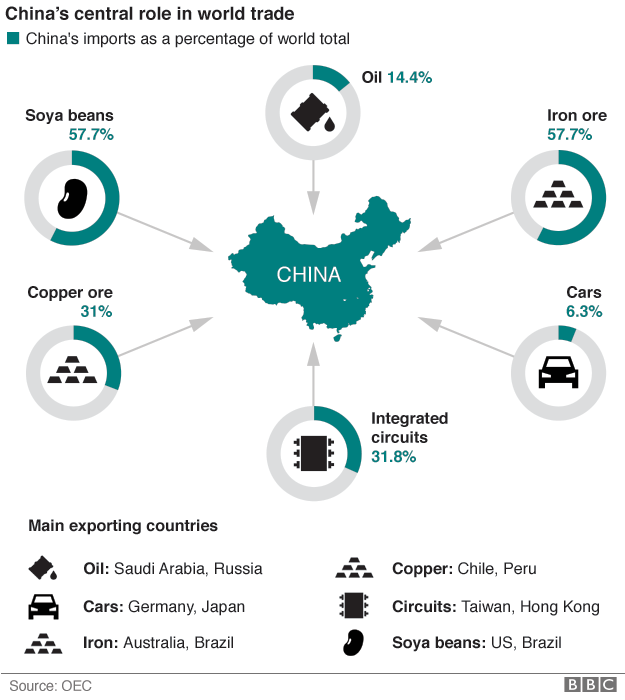

And China emerged as a major source of finance for investment in new commodity extraction and helped boost the international market price for African exports.

The consultants McKinsey estimated, external a quarter of Africa's economic growth between 2002 and 2007 came from energy, metals and other natural resources. There was a further indirect contribution in the shape of government spending financed by revenue from taxes on resource industries.

More on China in Africa:

The BBC is running a series of pieces about China's role in Africa ahead of the China-Africa summit on 4-5 December in South Africa.

In the first decade of the century, base metal and energy prices gained by more than 160%, according to the World Bank. For precious metals, the rise was above 300%, and for agricultural commodities over 100%. Chinese demand for commodities was a key force behind these rising prices.

New projects with high costs or in inaccessible locations were made more profitable.

Demand from China was a boon for African commodities, but Chinese growth is now slowing

But now, the commodity price boom is over. Oil, copper, and aluminium have all fallen by about half from the peaks they reached in the past few years. Iron ore has fallen even more. And these are all important exports for a number of African countries.

To take one example, the international commodities producer and trader Glencore has decided to suspend production at copper mines in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

And China's slowing growth and its shift towards service industries is a central part of the explanation.

The IMF says oil exporters are facing a formidable adverse shock, external. The big ones are Nigeria and Angola, and they generally get half of government revenues from oil-related activities.

The lower oil price will probably lead to investment in new oil production capacity being postponed. The IMF suggests this is especially likely in East Africa.

Angola is one of the continent's biggest oil producers

Africa's biggest oil producers are indeed seeing slower growth this year - Nigeria 4% after 6.3% last year, and Angola 3.5% compared with 4.8% in 2014.

Strong supply from oil cartel Opec countries and from North American shale oil is perhaps the key force driving prices down. But cooling demand for oil from China is probably also involved.

Exporters of other commodities account for 40% of population and economic activity of sub-Saharan Africa. They too will be affected by the decline in prices, but the IMF says the impact will be less than on the oil exporters and they will also get some benefit from cheaper oil.

It will enable them to reduce spending on fuel subsidies - or if the lower price is passed on to users, there should be a boost to consumer spending.

All the same, the World Bank is concerned about the impact, external. It said earlier this year: "Revenue dependence on the commodity sector remains high."

And if governments scaled back on social services and infrastructure, "gains in poverty reduction could be lost and prospects for future growth could be damaged by growing infrastructure deficiencies and bottlenecks".

Thousands of Zambians rallied to pray against the country's economic woes last month

Zambia's central bank raised interest rates sharply a couple of weeks ago, up to 15.5%, to curb the inflation that had resulted from a weakening currency, which was in turn down to the decline in the price of the country's copper exports.

The economic growth expected in Africa in the next few years is perhaps a bit of a disappointment after the first decade of the century. Faster growth would do more to ease the continent's persistent poverty problem.

But even so, it is a very different and brighter prospect than what Africa went through in the 1980s.

- Published27 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published24 July 2015

- Published24 July 2015