How to sell movies in the land of piracy

- Published

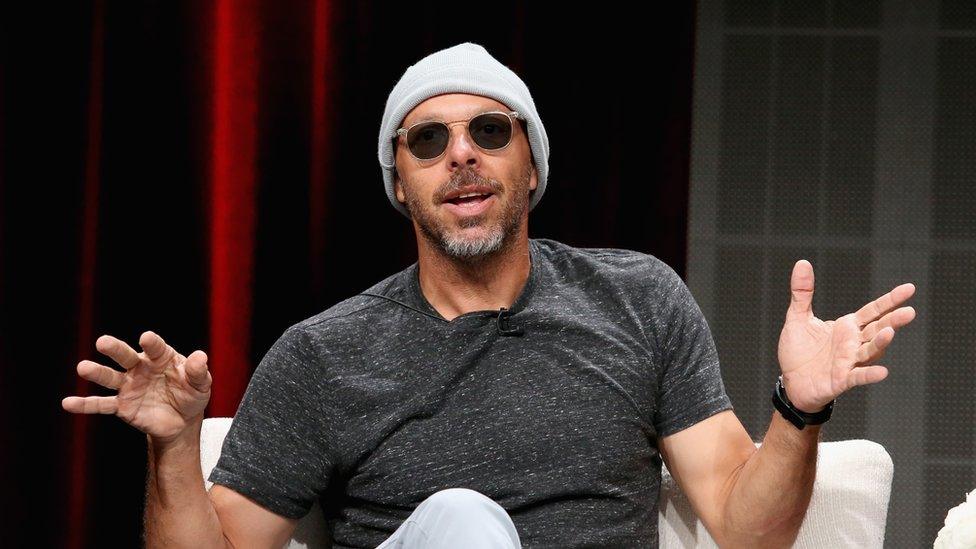

Film director Jose Padilha was not very happy with the former Brazilian culture minister

In 2007, the acclaimed Brazilian movie director Jose Padilha pulled a daring stunt on the country's then Culture Minister, Gilberto Gil.

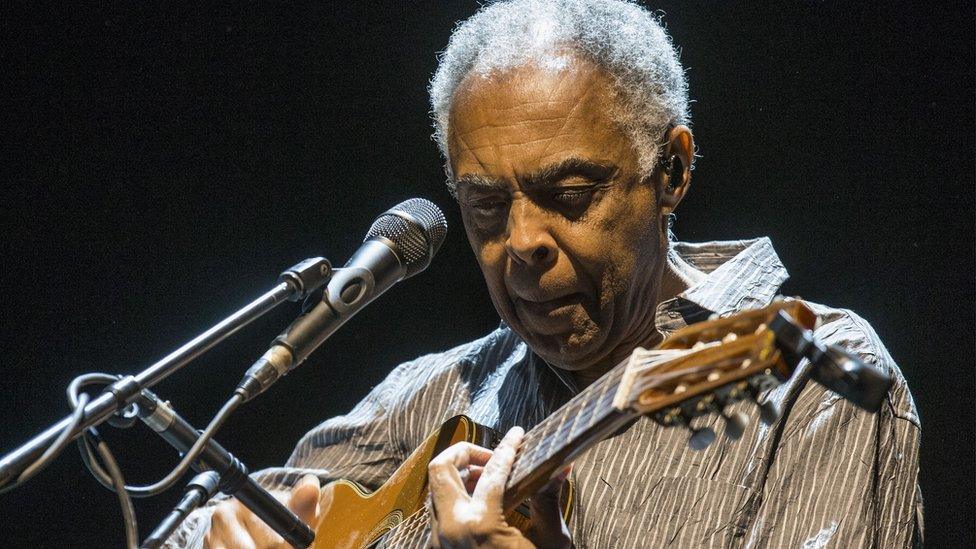

The filmmaker got word that Gil - also a famous musician - was hosting a prestigious viewing session of Padilha's first feature film "Elite Squad" at his house.

Padilha was furious, as his movie had just been released in cinemas. But a copy of the film leaked during post-production, and hit file sharing websites four months before its official release.

It became a piracy "super-hit" in Brazil. Some analysts estimated that more than a million people watched illegal copies of "Elite Squad" before the movie ever hit the big screens.

When Padilha heard that the culture minister was about to be part of that statistic, with an illegal copy of his movie, he evaded security and knocked on Gil's door demanding the pirate DVD be handed to him - which was promptly done by an embarrassed servant.

'Rocket-ship'

Brazil has long been a haven for movie piracy.

A government study found that 41% of Brazilian internet users have downloaded content illegally from the internet.

Gilberto Gil was said to be planning to watch hit film Elite Squad illegally

Piracy is also prevalent on the streets - with DVDs being openly sold in most commercial places and roads, and even outside movie theatres.

So Brazil is an unlikely place for movie subscription service Netflix to be successful.

Yet, since it was launched in Brazil in 2011, Netflix subscriptions have soared in the country.

The company does not release country-specific numbers, but two independent studies suggest Brazil has over the years become the fourth-largest market for Netflix - after US, Canada and the United Kingdom. The company has 69 million users worldwide.

Analysts agree that Netlix is helped in Brazil by its low prices

Netflix's chief executive Reed Hastings - who usually refrains from commenting on countries - says Brazil is a "rocket ship" for its company.

When Netflix's Brazil and Latin Americas service started in September 2011 it was the firm's first venture outside of North America.

The region was chosen for three primary reasons - broadband penetration was considered big enough as a market, incomes at the time were rising rapidly, and there was an appetite for Hollywood content.

Netflix's chief communications officer Jonathan Friedland says there was another important reason that facilitated their entry.

"In Europe you have to buy individual content licences for every movie or TV show in each country, such as France, Germany or Spain," he says.

"In Latin America, you only need to two licenses - one for all Spanish-speaking countries and another one for Brazil."

Pricing

Netflix's strategy against piracy was put to the test in Brazil, a country where users and sellers are rarely brought to justice for that crime.

The company decided to beat piracy by being competitive.

Netflix has been operating in Brazil for four years

"If you offer good content at low prices and rapidly - releasing series in the same moment in Brazil as people are getting them in the US - that makes piracy less enticing," says Mr Friedland.

One of the key elements in its strategy is pricing. Netflix subscriptions in Brazil vary from 19.90 to 29.90 reais ($5 to $7.50; £3 to £4.60) a month. One movie ticket alone in Sao Paulo costs 30 reais ($7.50).

For that same amount of money you can buy about 10 illegal DVDs in the streets, but the quality is not always reliable.

And while many Brazilians illegally download films and TV shows, others are either not technologically savvy enough to do so, or are too concerned about computer viruses and malware.

For commentator Sergio Branco, director at the academic think tank Instituto de Tecnologia e Sociedade do Rio de Janeiro, Netflix's low prices is a key factor behind its success, making it more attractive to users than online piracy.

Netflix's boss Reed Hastings says Brazil is a "rocket ship" for the firm

He also praises the firm's subscription-based model, which is mirrored at music streaming service Spotify, and online book provider Oyster Books.

Mr Branco says: "Instead of charging for a movie or a song or a book, these services charge a monthly fee for people to have access to a vast archive of cultural services."

Mr Friedland adds that when Netflix enters a country, the rates of internet file sharing drop.

"Most people don't want to steal," he says. "They don't want viruses in their computers, they don't want the hassle of it."

In addition to getting its pricing right, Netflix also had to work hard to adapt to local consumer habits, such as issuing pre-paid cards, and getting partnerships with local banks to allow payment for users who do not have credit cards.

Brazil's often low-quality internet connections also tested the company's adaptive streaming technology - that adjusts the quality of video transmission according to available bandwidth.

Crisis 'helps'

According to Netflix, Brazil's current economic woes is not hampering business there, as its product is seen by consumers as a cheaper alternative to going out.

Netflix chief executive Reed Hastings said earlier this month, in a presentation of the firm's latest results, that its base in Brazil is still growing, despite the economic contraction.

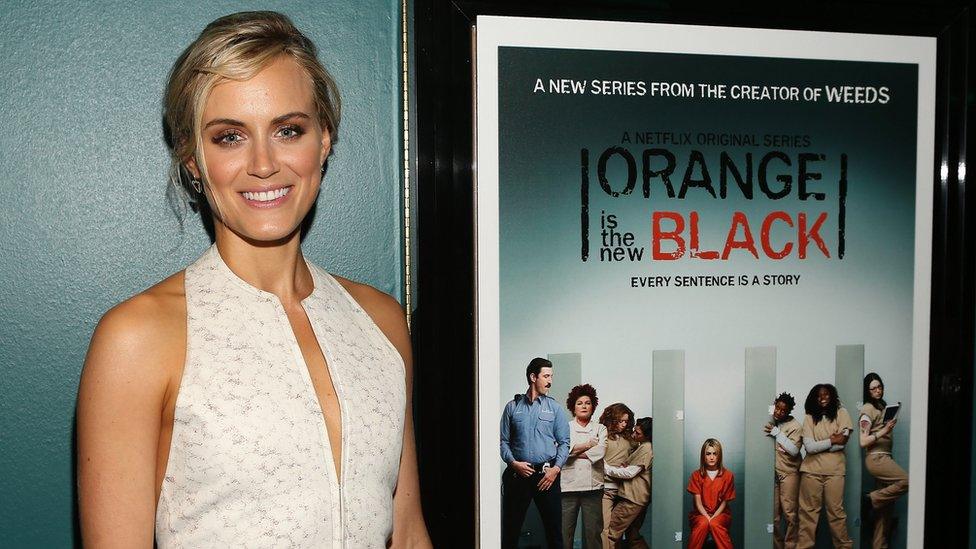

Netflix has grown strongly in popularity around the world in recent years

He said: "In Brazil, a value-based product that is very inexpensive is appreciated. Even though there are tight economic times currently, that has not held back our growth."

But what does hit Netflix is currency fluctuation. This year's appreciation of the dollar has made some international markets less profitable for shareholders in dollar-terms - particularly in Brazil, where the currency has lost 30% in value.

According to Mr Friedland, Netflix is still in "rocket ship" mode in Brazil, and now attracting content producers in the country.

Four years ago the company was approached by Jose Padilha - the same piracy-aggrieved movie director - who proposed a series about the history of cocaine in Latin America.

The Netflix original "Narcos" - based on the life of Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar - premiered in August and was an international success.

In Brazil, it went down particularly well, with national star Wagner Moura in the main role, and music by popular singer Rodrigo Amarante.

Now Netflix wants to draw content out of countries like Brazil and launch it globally.

The company recently had a contest for young Brazilian filmmakers and gave global distribution to the winner's production. Next year it will launch "3%", a science-fiction series set and produced in Brazil and spoken in Portuguese.