Why the boss of Lush likes to get up people's noses

- Published

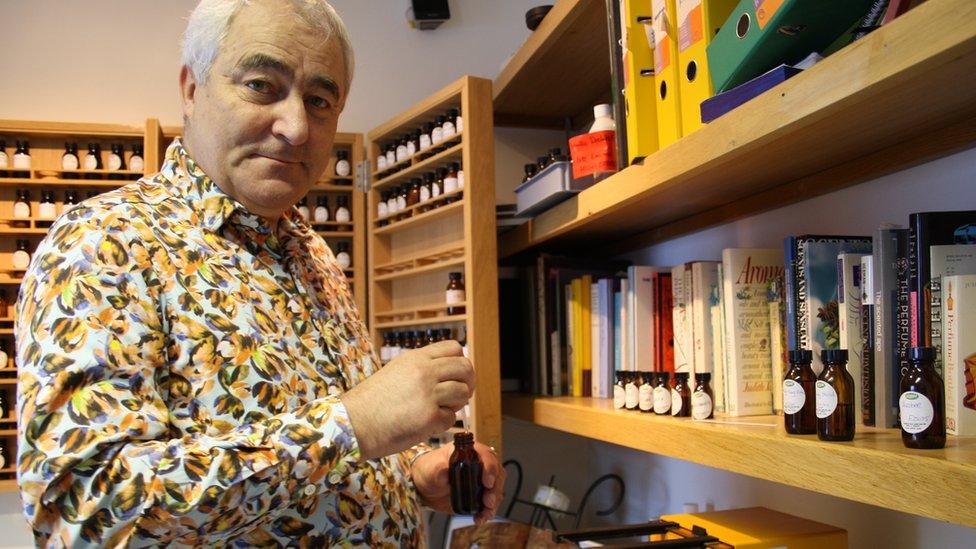

Mark Constantine breaks off from experimenting with his bottles of perfume ingredients - it turns out that orange and lime smell a bit too much like urine.

But he's found a more serendipitous combination of lavender and sandalwood.

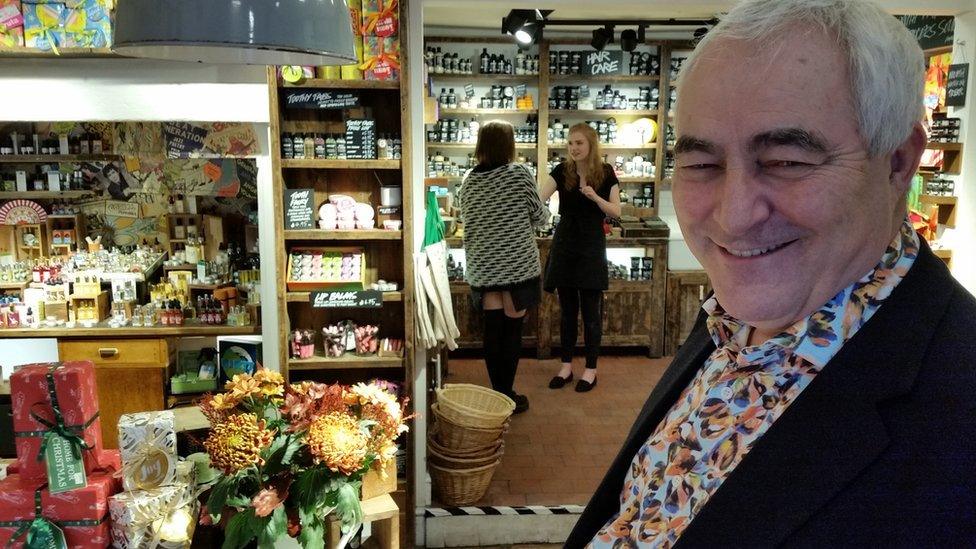

The 63-year-old is the founder and chief executive of the notoriously heavily-scented UK toiletries and cosmetics firm Lush.

He's pausing to consider a plan that he hopes will rock a few boats. A couple of colleagues have brought him a prototype cinnamon-scented soap, each piece of which has a cardboard tab attached to it with the message #BeCrueltyFree in both English and Mandarin.

Lush doesn't sell soap, or anything else, in China, but that doesn't mean it hasn't got something to say to the Chinese, where the debate over cosmetics testing on animals is continuing.

Put Santa in the bath and he smells of jasmine

There's quite a demand for Lush products imported on the grey market there, so the company is exploring how it might use this illicit trade to raise awareness of the issue.

Lush, vendor of bicarbonate-based bathbombs and soap that looks likes psychedelic wedges of cheese, is known for two things - pungent, fruity-floral odours that are not universally appealing, and its provocative campaigns against everything from fox hunting, to fracking and international trade deals.

'Childish'

Mr Constantine appears to relish the way the brand divides opinion, delighting in what he calls his "mischief".

A case in point was his 2014 legal spat with Amazon, over the way the internet giant used the adjective "lush" to sell non-Lush products. His chosen strategy was to trademark the name of Amazon's UK boss and threaten to launch a product range using it.

Lush's first shop is in Poole, Dorset and still houses some of the company's development work

Lush staff experiment with natural ingredients from fresh flowers to seaweed

"You have to get people to realise what it's like when they use someone else's brand," says Mr Constantine, who admits that it wasn't the most grown up approach to resolving the problem.

"Childish and vindictive could be words to describe me. I have heard them used before," he chuckles.

In fact, he appears as interested in causing a stir as he is in making profits. Some years ago a piece of performance art took place in a Lush shop window, which showed a young woman being treated like an animal undergoing testing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it provoked strong criticism, not least from women who had been victims of violence, and Lush was accused of sensationalism. But Mr Constantine doesn't think it went too far.

"There will be times we've made mistakes, but not in that instance," he says.

"It upset me - I don't like the thought of animals being treated that way, I certainly don't like the thought of people being treated in that way. But it doesn't hurt to be reminded."

Mr Constantine says he is happy to take any criticism

Mr Constantine's campaigning has also, it appears, caught the attention of US authorities.

The last time he tried to go to the US - four years ago, shortly after a Lush campaign against the detentions at Guantanamo Bay, which used the strap-line "Fair Trial My Arse" - Mr Constantine was taken aside at immigration.

"I could see them smiling when they read my file," he says.

"I just sat with my head down, kept my mouth shut. After a period of time they called me to the desk and said I was free to go."

And this year Lush was accused of cashing in on the 2011 London riots, with the release of a perfume called the Lavender Hill Mob.

Named after an area of south London affected by the disturbances, the label featured a drawing of a burning building.

Mr Constantine insists that Lush was celebrating the groundswell of community sprit in the face of the violence and destruction, not glorifying the riots themselves.

'Showing off'

Far from resenting all the criticism he gets, Mr Constantine seems to relish the fight. Perhaps because it hasn't been plain sailing to get to this point.

As a child, a difficult family life left him, aged 16, homeless and dependent on friends and charities.

A different kind of attention: Mr Constantine and his wife were awarded OBEs in 2011

A few years later, whilst working as a hairdresser in the late 1970s, he wrote to Anita Roddick, founder of an exciting new ethical brand - The Body Shop, to tell her about his natural haircare products.

Mr Constantine's then business - Constantine and Weir - eventually became The Body Shop's main supplier, until the Roddicks bought all the rights to its products in 1992 for £9m.

With the windfall he and his wife Mo set up a mail order company, Cosmetics to Go, but in less than 18 months it was clear it wasn't going to work.

"It was uncontrolled creativity, £9m and untrammelled creativity."

He says the money from the sale to the Body Shop meant they could all indulge their interests, but gave little incentive for discipline.

Lush staff test new bath bomb combinations in a large basin

"I was showing off," admits Mr Constantine.

There was a period then when he felt overwhelmed with shame at Cosmetics to Go's failure.

"After that my colleagues fished me out and dusted me off, and said 'we're going to do something else'."

Which was when Lush was launched in 1995, out of the same warren of little rooms in Poole, Dorset, where Cosmetics to Go had operated. But this time it was with next to no capital.

Lush by numbers

7 factories in UK, Croatia, Australia, Canada, Japan and Brazil

933 shops around the world

£454m turnover in year to July 2014

Once the company was established, Mr Constantine even offered to buy The Body Shop, which the Roddicks had decided to sell, due to Anita's terminal illness.

They turned him down, selling instead to corporate giant L'Oreal in 2006, something which still upsets him. Lush represents just a tiny fraction of the enormous global cosmetics industry, but Mr Constantine says he wouldn't ever sell his own company to a big player.

Mr Constantine likes to dabble with perfume blending alongside running the company

Angry with the Roddicks at the time, he put up banners at Lush stores saying "Are you fed up with the BS?"

"I might be slightly ashamed of that now," says Mr Constantine. He hadn't realised how ill Anita was.

But for the most part he's prepared to take whatever reaction he gets for his belligerent approach.

"If you're going to shove your head above the parapet, you are going to be sniped at," he says.

And while these campaigns certainly rile some people, Lush has avoided the most obvious pitfall of a company that takes an ethical stance on so many issues.

"So far, Lush has managed to avoid heavy criticism for being deceptive, or misleading, in its claims in terms of product," says Anusha Couttigane at retail analysis firm Conlumino.

"While you can question its methods when it comes to public debate, it hasn't been called out for hypocrisy."