Is there an economic case for tackling climate change?

- Published

A coal mound in Kentucky: coal is the largest domestically produced source of energy in America

What is the economic case for tackling climate change? And if that case can be made, what's the best way of going about it?

And, yes, this is all based on the assumptions that policy makers are taking with them to the Paris conference: that the climate is warming due at least partly to human activity and it is possible to slow or halt that process.

Economists have been wrestling with the question since at least the early 1980s.

The approach most often adopted is to treat the problem rather like an investment appraisal, to do a cost-benefit analysis - though this method has its critics even among economists, external.

A gas engine plant in South Africa: developing countries are also under pressure to cut emissions

The investment side of it is shifting the world to an economic system that produces much less by way of climate changing gas emissions, or even none at all.

You then compare the cost of doing that with the benefits, in the shape of climate-related harm avoided.

It sounds straightforward. But of course it isn't.

Measuring both elements -the costs and the benefits - is fraught with difficulty.

So is a third factor: how you compare costs in the near future with more distant benefits. More on that later.

'Greatest market failure'

There's another way of looking at it.

One of the basic ideas in economics is that you tend to get the best results if people or businesses that take decisions have to take account of all the benefits and costs.

Pollution is the text book example of a situation where that may not happen. The polluter has no incentive to consider the impact of the pollution.

It is what economics textbooks call an externality, which in turn is one example of what they call "market failures".

The standard economic analysis of climate change sees in those terms.

There are externalities: emissions produced by a person or business lead to costs - and sometimes benefits - for others which the emitter has no incentive to consider.

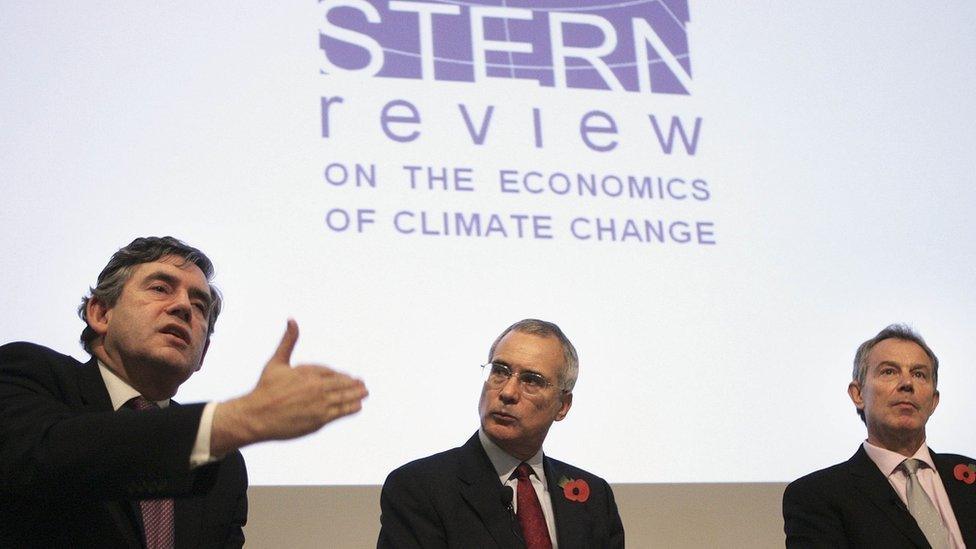

The Labour government presented Sir Nicholas Stern's review in October 2006

Lord Stern, formerly the chief economist to the British government wrote in a major - and controversial - economic review, external : "Climate change is the greatest market failure the world has ever seen."

Taxes

What do you do about it if you accept that view? The mainstream economic view of how to deal with an undesirable externality is that you tax it.

It's called a Pigouvian tax after the British economist Arthur Pigou who set out the case in a 1920 book.

In this case it is greenhouse gas emissions that would be taxed. This approach is generally known as a carbon tax or sometimes as a carbon price.

There are alternatives, notably emissions caps with tradable permits.

The idea is that the curbs in emissions would be made by those businesses that could do it at the lowest cost.

There have been experiments with this approach, notably in the European Union.

If implemented effectively the approach does have much in common with a carbon tax.

Emitters have to pay and in doing so are in effect forced to take account of the externality.

The other main approach has been to use regulation or subsidies to promote particular low emissions technologies, especially in electricity generation.

This method is less appealing to the mainstream of economics.

Markets are generally seen as more effective than governments, although needing a bit of a nudge in cases of market failure, such as climate change.

The carbon tax approach sits more squarely in this tradition. It could also be simpler to run.

Professor Richard Tol of Sussex University suggests that running a carbon tax in the UK would just need ten or so civil servants in the Treasury, external.

If we had such a tax, how much should it be? It should be equal to the damage that would be done by an additional unit of emissions.

Campaigners protesting about uncapped shipping emissions

But what on earth is that damage? There are several layers of uncertainty. How sensitive is the climate to emissions? How much damage would be done by any specific amount of warming?

Moderate warming might actually be beneficial at least for some, with reduced heating costs and cold weather related health problems, and increased crop yields in some places.

But how rapidly does the impact deteriorate at higher temperatures?

And how should we factor in the possibility of damage that is seen as unlikely but very detrimental if it were to happen - what are sometimes called catastrophe or tail risks?

Discounting the future

Then there's the fact that much of the damage there might be from unabated emissions will be in the future, decades, even centuries ahead.

The usual practice in economics and in any investment appraisal is to "discount" future costs and benefits to give what's called the present value.

That's to say you take that future cost, apply a discount rate to it and you get a lower value present value.

Suppose you are looking at $1bn worth of damage in 100 years.

Spending the same amount today to avoid it would be a poor investment.

If you invest a lot less in something else that's profitable it could yield $1bn in 100 years to provide compensation for all the damage.

Another argument for discounting is that people will, it is generally assumed, be richer than we are now, perhaps a lot richer when we are thinking in terms of decades and centuries ahead.

They can afford the hit to their standard of living better than we can.

There is also the idea that people are impatient - that given the choice between a bundle of goods today and in the future, they'd only accept the future date if there was more on offer.

There are some difficult ethical judgments here.

It's all very well to "discount" your own future income or spending.

But is it right to do that for people who haven't even been born?

The result is you get different views about the right discount rate to use, external.

The choice makes a huge difference to how much it makes sense to pay to avoid climate damage in the future.

If you take the annual discount rate used in the Stern review, 1.3%, which is about as low as any, then to avoid $100 of damage in a hundred years from now, it would make sense to pay $25 today.

If you go for a higher rate of, for example, 5% you get 76 cents.

A low discount rate supports the case for a very high carbon tax now.

A higher rate suggests a more moderate tax now rising over time.

Professor Martin Weitzman of Harvard suggests another approach.

He wants to put more emphasis on the possibility of catastrophic climate change, external - scenarios with probabilities that he suggests are low but not negligible.

"The primary reason for keeping greenhouse gas levels down is to insure against catastrophic high temperature climate risks."

There's an old joke about economists (attributed to George Bernard Shaw): if you laid them all end to end they still wouldn't reach a conclusion.

Well it will be politicians in charge in Paris not economists, so maybe they will.