How much inequality is too much?

- Published

The richest 10% of Americans earn half of all of income. In Britain, the top 10% hold 40% of all the income.

Inequality isn't just an issue for rich countries: a billion people have been lifted out of poverty since 1990, but inequality has also been rising in many countries too.

Four experts talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme about the effect inequality has on growth and prosperity.

Deirdre McCloskey: Capitalism is not the enemy

Deirdre McCloskey is Distinguished Professor of Economics, History, English, and Communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The daughter of a Harvard Professor, her brother became a university cleaner.

"You can't force people to take advantages that are placed in front of their nose, and that's my brother's case. No amount of income redistribution or socialist schemes to give my brother more opportunities would have made any difference at all to his life.

Occupy protesters have highlighted the gap between the wealthiest 1% and the other 99%

"If people strive, some of them succeed and get rich, at least momentarily until other people strive and compete with them. This striving turns out to be good for all of us.

"The percentage of people in the world living on $2 (£1.30) a day - an appalling level of income - has halved in the last 30 years. That's not by foreign aid or redistribution. It's by letting the economy function in a more innovative way.

"The wrong way to cure inequality is to attack the people who are taller, or have better parents, or live in richer countries. The way to do it is to uplift the poor. I approve of being taxed to help the very poor. But I don't want to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs. Capitalism is not the problem, it's the solution.

"The growth in the last couple of centuries has been astounding. It's a factor of 30 - about 3,000% per head for the average English or American person. Explosive, unprecedented growth. Meanwhile, inequality has gone up and down a little bit.

"If you were to make a rule that the chief executive could only earn 50 times the shop floor employee, that would not reduce inequality substantially.

"I'm very relaxed about [inequality] as long as it's not force or fraud that caused it."

Jared Bernstein: Inequality impedes growth

Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington DC, and a former economic advisor to President Obama.

"I was a member of the President's economics team during the worst recession we've had since the Great Depression. The responsibility to try to turn that around was huge.

"This wedge of inequality between growth and the income of working families undermines the basic incentive that hard work will be rewarded.

"I call it the shampoo cycle - bubble, bust, repeat. And because middle and low income families lack the income growth they used to see, they borrow to make the difference. That creates large leverage bubbles which explode and hurt growth.

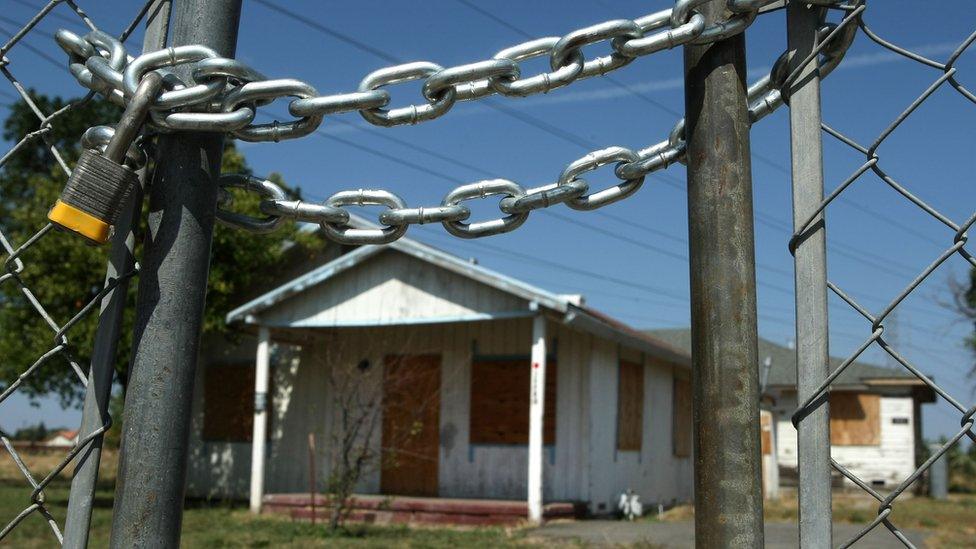

"Once wage inequality gets too high, and you have lots of low income people stuck in tough neighbourhoods that are segregated by income and race, and they have fewer libraries and a more difficult learning environment, you begin to see this connection between high levels of inequality and barriers to opportunity.

"You don't necessarily see that in today's economy because that's a cumulative process, but it's very possible that we'll see that in economies 20 years from now when these children come into the job market.

"If you go back to the period where productivity and incomes for middle class families were growing together - in the US that would be back to the mid 1970s - you'll see that the top 1% held about 10% of all income.

"Now it's 20 times that. That's too much. I'm not saying we necessarily have to get back to the late 1970s level, but I do think that a good metric here would be that the income of middle income families would grow closer to the rate of productivity growth, and that's something that we haven't seen for a while."

Jonathan Ostry: Opportunity more important than inequality

Jonathan Ostry is deputy director of the Research Department of the International Monetary Fund.

"We don't have a threshold level for how much inequality is too much. We don't have a magic number. Sometimes a rise in inequality is perfectly compatible with healthy growth and prosperity, and in other cases the rise has gone way too far.

"When China opened up, it not only took off in terms of economic growth, but there was a marked and quite significant increase in income inequality. I'd be prepared to venture that was a good increase in inequality. Sometimes you need to have a little bit more inequality in order to get growth going as part of deregulating of your economy.

The Bolsa Familia programme to tackle poverty was a centrepiece of former Brazilian President Lula's social policy

"Think of the very high levels of inequality that prevailed in Brazil when President Lula came to office, and the steps he took with the Bolsa Familia conditional cash transfer programmes. His policies were successful without jeopardising economic growth.

"I would want to be sure that in a country with a lot of inequality those at the bottom still had opportunities to be well-educated, to have adequate nutrition, and were not shut out from credit and banks. Likewise if there was a fair degree of equality, but nevertheless those at the bottom didn't have adequate opportunities, I'd be concerned.

"So for me it would be more a question of whether there were adequate opportunities for the less well-off in society. Provided that was the case I wouldn't be overly concerned that a given level of inequality was causing great harm.

"[However] it turns out that income equality is an important factor in separating countries that have been successful at sustaining growth for long periods, versus those that have enjoyed spurts of growth which have fizzled out rather quickly. Too much inequality can undercut the ability to sustain growth.

"In more equal societies, those that are more socially cohesive, governments are able to take measures that have buy-in from the population at large. Therefore they can right their economies more quickly.

"In more unequal, less socially cohesive societies, people don't buy the notion that if the economic ship is righted, everyone will benefit. They're more likely to oppose the painful short-term measures that governments need to take to right the economic ship. And so righting that ship becomes much more difficult in less equal societies."

Branko Milanovic: Beware rising inequality within countries

Professor Branko Milanovic has spent his career studying inequality, and is now a visiting professor at the City University of New York.

"We need inequality. Perfect equality, everybody having the same income, doesn't exist anywhere, nor has it. Obviously some countries - maybe China during the cultural revolution - came relatively close, but some inequality has always existed.

"Without inequality you lack incentives to do practically anything - to work, to invent new things or to invest. Nobody is going to do things for nothing and we know that monetary rewards are really crucial, so this is the good part of inequality. We should not forget that inequality is indispensible for the development of a society.

"Globalisation has been very good for the middle classes in the emerging markets - China in particular, parts of India, Thailand, Indonesia. They are still not level in terms of income with the middle class in the rich world, but it's improving, On the other hand, we have essentially a stagnation of middle class incomes in rich countries, a very interesting and a potentially politically destabilising development.

The economic disparity between the wealthiest and poorest in China is stark

"If the gaps keep on increasing as they've increased in the last 20 years, you would end up with two types of societies within a single country. If there is no sufficient middle class and if the poor really are very far from the rich, then you really cannot speak of a single society.

"We could end up with a kind of a global plutocracy, this global one per cent or even half a per cent that are very similar among themselves, but really belong to different nations.

"We might have a situation that most of global inequality is due to inequalities within nations which was more or less the situation 200 years ago. So we may be really going back to the situation that existed before the industrial revolution."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published21 May 2015

- Published14 May 2015

- Published19 January 2015

- Published19 January 2015