Could gifting free money boost the economy?

- Published

Imagine waking up one morning to the sound of a helicopter overhead. You look out and see packages dropping in front of every home on your street.

Inside each package is $10,000 (£6,700) in new bills, a gift of freshly-printed money from your government with no strings attached. What would you do?

Economists hope you and your neighbours would go shopping, and that your spending would help kick start stagnating post-industrial economies.

Four experts talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme about whether so-called "helicopter money" - more likely to be delivered electronically - could be the answer.

Adair Turner: Take the medicine, but beware overdosing

Adair Turner became chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority five days after Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008. He is the author of Between Debt and the Devil: Money, Credit and Fixing Global Finance.

"It was an extraordinary period. A financial system collapsed entirely, and I did not know that the recovery would be so deep. I certainly did not know in 2008 that in 2015 I would be making the case for overt money finance [central banks printing money to give directly to people].

Lehman Brothers was once the fourth largest investment bank in the US

"When Milton Friedman talked about this strategy [in the 1960s], he used the analogy of 'helicopter money': filling a helicopter with dollar bills and simply scattering them. Remember, the economists who talked most about this in the past are not crazy left-wing inflation-loving socialists. We have been left with so much debt we can't just grow our way out of it - we should consider a radical option.

"Suppose the Federal Reserve agreed a total level of stimulus, agreed that the easiest way to do it was a tax rebate, and let's use the figure of $10,000 (£6,700): you literally send them a cheque.

"There's a good argument for doing it as an equal amount for everybody because that would give more of the money to middle-income and poor people, who are most likely to spend it.

"That will then tend to produce an increase in employment and activity, as people spend more money on cars or washing machines or clothes or restaurant meals or whatever they choose to spend money on.

"The danger is the political danger. You break a taboo. People say 'Oh, well, if that's possible, I'd like to do it all of the time, and in inappropriately large amounts, and just coming up to an election I want to win'. So that's why it is a dangerous proposal, and needs to be tightly constrained.

"In the early 1990s, I was involved in advising the Central Bank of Romania at a time when they had 300% inflation, because the central bank was essentially financing the public deficit.

"It's like a medicine which, taken in small quantities and in appropriate circumstances can be beneficial, but taken in overdose is fatal. You've got to decide whether you're so terrified that you'll take the overdose that you throw it away, and refuse to use it in all circumstance, but that will have a disadvantageous effect."

Richard Koo: Helicopter money undermines trust

Richard Koo is chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute, and an economic adviser to successive governments in Japan, which has struggled to grow for decades.

"I don't think [helicopter money] is a very good idea because the trust people have in their national currencies is the most important economic infrastructure of any country, and if you start giving money just like that to households, then people will begin to wonder whether this money is going to be worth anything tomorrow.

"If you get a big cheque in your mailbox from the government you'd be very happy, but then you realise that everybody else got the same cheque at the same time then you begin to worry.

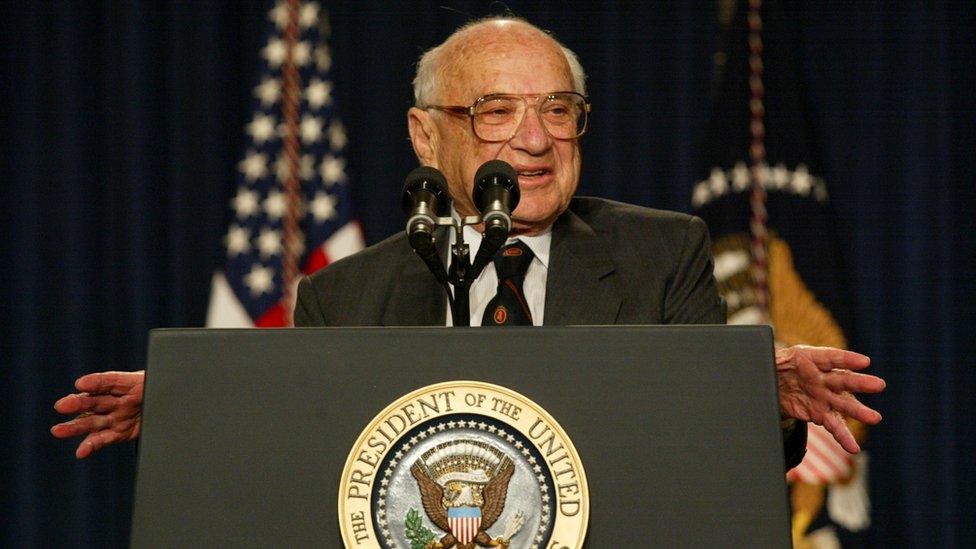

Economist Milton Friedman first proposed the notion of "helicopter money" in the 1960s

"As a buyer you rush to the shops and get your stuff. But if you're the seller of the goods, and you realise the government is printing money left and right, and you will never know when this will actually stop, then I'm sure quite a few of those would just shut down their shops or demand foreign currencies or gold.

"If people begin losing confidence in the value of their currencies, the economy actually shuts down instead of expanding like Milton Friedman said.

"I would argue that those economies, especially those in the eurozone, perhaps the UK as well, should understand that the private sector is not borrowing money, is actually minimising debt [despite] zero interest rates, which puts us completely outside conventional economics, because all the economics we learn is based on the assumption that the private sector maximises profits.

"So we're completely outside that world, and in that world and in that world only, the government must act as a borrower of last resort to get both the economy going and money supply from shrinking.

"This has to continue until the private sector balance sheets are repaired, and then once the private sector is willing to borrow money, then you reverse course, but the government has to be in there to make sure that the private sector balance sheets are repaired."

Mohamed El-Erian: Wider reform needed

Mohamed El-Erian is chairman of President Obama's Global Development Council.

"[Helicopter money] is not a first best policy response because it doesn't address what really ails the western economies.

"We have not invested in genuine growth engines. We haven't invested enough in infrastructure, we haven't reformed our corporate tax system, we haven't invested enough in retooling and retraining of people.

"In addition, we also have what's also called 'the debt overhang', excessive pockets of indebtedness that do two things. They cripple the over-indebted - think of what's happened to Greece - and they discourage new capital, new oxygen, from coming in.

"And we have an incomplete [economic] architecture, both at the regional level in Europe and at the global level.

Does the West need an "economic Sputnik moment" in echo of its political response to the Soviet satellite launch in 1957?

"So can helicopter money help? Yes. It can help by somehow increasing consumption and a little bit of investment, but it's not going to make a durable change, meanwhile there are unintended consequences.

"Firstly, it exposes central banks to political interference. 'Wait a minute, how can a central bank produce money and give it to people, a fiscal action, without parliamentary approval?' So suddenly the independence of central banks gets threatened.

"Secondly, this is not a genuine promoter of economic growth, this is an artificial promoter, and it tends to encourage artificial behaviours. And those can in turn undermine future growth. Finally we're not really addressing our growth potential, we're just trying to get some short-term stimulus.

"What we need is a political Sputnik moment. In the late 1950s when the US woke up one morning to the reality that the USSR had succeeded in launching and sustaining the Sputnik satellite, suddenly the US felt threatened and the political system came together.

"We need an economic Sputnik moment. A realisation that this quest for growth is critical not just for this generation but for the next generations as well, and that requires the political system responding."

Professor Barry Eichengreen: Look to technology to boost growth

Barry Eichengreen is professor of economics and political science at the University of California, Berkeley.

"In the current environment, I think people would go out and spend some of that [helicopter] money. We are in a situation now where firms are not spending, investment is not taking place, governments are not spending on infrastructure. So one way to boost the level of spending would be to give money directly to households. Whether that would be politically feasible, of course, is another matter.

"I don't think it's correct to argue that slow growth inevitably follows a deep recession and a financial crisis. People are worried about what we call 'secular stagnation' and the possibility that somehow the engines of innovation are no longer working as they have in the past. We have 200 years of history that runs counter to that pessimistic conclusion.

Could robotics provide the same kind of economic boost as the internal combusion engine?

"The very phrase secular stagnation dates from the 1930s when people were pessimistic as a result of the Great Depression, and then we had the jet engine, radar, television. We had a period of rapid growth based largely on technologies developed in the 1920s and 1930s and during World War II.

"[New technologies] often reduced productivity growth initially until we figured out how to reorganize the economy to take advantage of them. It took decades in the case of the steam engine, electricity, the internal combustion engine; and we could be living through a period of disruption and temporarily slower productivity growth similar to those earlier episodes right now.

"Artificial intelligence, robotics, biotechnology all have the potential to be as revolutionary for the economy, for living standards, for economic growth as the internal combustion engine or electricity before that."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.