Why is it so hard to decide on major building projects?

- Published

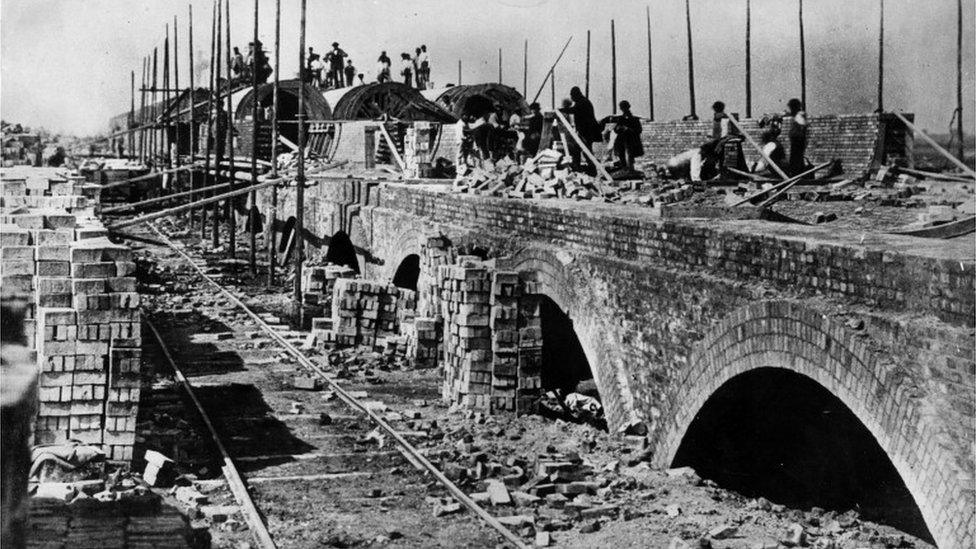

The building of Britain's sewer system was seen as a triumph of political will

Prime Minister David Cameron could not have been clearer about the impact of delaying major UK infrastructure projects.

"The costs of delay are felt in businesses going bust, jobs being lost, livelihoods being destroyed," he told the CBI employers' group. That was in 2012.

Winning approval for major infrastructure investments has long been fraught with politicking and protest.

Airport expansion is just the latest in a long list of problem projects.

The bill for upgrading the West Coast Main Line from London Euston to Glasgow and Edinburgh cost six times more than expected at £14.5bn.

The Channel Tunnel rail link, running through Kent into St Pancras station, was criticised by the National Audit Office for its "hugely optimistic assumptions" about passenger numbers and costs.

Deciding whether to build new nuclear power stations took years - and then hit a problem of who would pay for them.

Then there is the HS2 high-speed rail project. After years of consultation, HS2 looks to be going ahead. However, the precise details have not been finalised, and the bill for the first stage has yet to go through parliament.

Now, a decision on whether to build a new runway at either Heathrow or Gatwick airport has been postponed for another six months. Still, after several decades of wrangling, what's another six months?

Construction of the Mersey Gateway bridge is due to be completed in 2017

Rhian Kelly, business environment director at the CBI, says that once a project gets the green light, Britain tends to move very fast. It's arriving at a decision that is the tortuous part.

"By the time a decision is made, our competitors have often caught up or moved ahead," she says.

'Not generous'

Not all projects get mired in a political cul-de-sac.

Richard Threlfall, UK head of infrastructure at the business advisory group KPMG, points to major successes, including the Mersey Gateway bridge, the Manchester Ship Canal, and Crossrail, the first complete new London underground line in more than 30 years.

Both look likely to come in on time and on budget, he says.

The UK planning process, which used to be much slower than in other countries, has been significantly improved, Mr Threlfall argues. And some projects can be fast-tracked to an early decision.

A decision to build the Thames Tideway - a sewer running up to 20 miles from west to east London - benefited from this new streamlined process.

Yet, these examples seem to be the exception, not the rule.

One impediment to smooth decision-making is the relatively small size of the UK. Its dense population makes it harder to secure the space and necessary approval for big projects.

Improving the UK's "particularly ungenerous" compensation scheme would help, Mr Threlfall says.

Homeowners displaced by, say, the HS2 project, could be compensated up to the value of their home before the project was announced. But is that enough for someone whose life will be turned upside down?

More generous compensation would mean less opposition, and the extra financial outlay would be a drop in the ocean compared with a £50bn project, for example.

Mr Threlfall says the current compensation system "ignores the fact that the whole of the UK will benefit. So why should that cost be borne by just the people on the route?"

London Airport, at Heathrow, began commercial operations in 1946

Critics often accuse governments of short-termism. Infrastructure is a long-term issue, and governments can be reluctant to commit vast sums of money to projects that will take years to return benefits.

But Tony Travers, director of LSE London - a research centre at the London School of Economics - says the apparent reluctance to make decisions is usually due to politics, not resources.

"It is the government's sense of danger to itself that stops it making the decision. In west London [where Heathrow is located] the government has a lot of marginal constituencies and cabinet ministers who have seats in the area," he says.

Key test

It is hoped that the creation this year of a National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) - an independent body to oversee £100bn of spending on infrastructure projects - will help ease political indecision.

The commission will produce a report at the beginning of each Parliament and take a more strategic review, helping to take politics out of decision-making.

The NIC was recommended by Sir John Armitt, former chairman of the UK's Olympic Delivery Authority and head of a 2013 review of infrastructure planning.

He says its success will be a key test of whether the UK is prepared to change its ways.

Sir John says: "The Airports Commission was incredibly thorough. If [government] cannot make a decision after all its work, then you have to ask how it's going to be for the NIC."

Politics cannot be taken out of infrastructure, and nor should it be, he says. "But the role of politicians is to make decisions, even if they are unpopular ones."

The state of infrastructure planning is often compared unfavourably with Victorian times, when bigger sums of money in relative terms were spent on railways, bridges and sewers that are still used today.

Big picture

Sir John points out that many of these projects were controversial and loss-making.

But the Victorians had a vision, self-confidence and industrial drive that forced projects through.

Proponents were better able to garner a broader consensus that developments were in the national interest. In other words, there was more emphasis on the "big picture".

Sir John believes that the focus today is too narrow, with too much emphasis on rigid cost-benefit analysis.

The costs of a project are added up, along with the benefits. And, hey presto, the financial pros and cons stretching over a couple of decades are deduced.

There needs to be much more socio-economic analysis, says Sir John. "We look at some projects today [the Channel Tunnel or London's Jubilee tube line, for example] and ask: how did we ever survive without them?" And yet both projects struggled to get off the ground.

Professor Diane Coyle says infrastructure projects are particularly inappropriate for standard cost-benefit analysis. The multiple variables make such an approach "simple in principle, but extremely difficult in practice", she wrote in the Financial Times earlier this year.

"In the UK, we seem particularly prone to short-termism… I think it is because we pay too much attention to the conventional economic approach to assessing projects.

"We have forgotten how to take the imaginative leap that inspired some of the most vital infrastructure of the Victorian age," she says.

- Published7 December 2015

- Published30 November 2015

- Published30 October 2015

- Published30 June 2015