Canada's maple syrup 'rebels'

- Published

Quebec is the world's largest producer of maple syrup

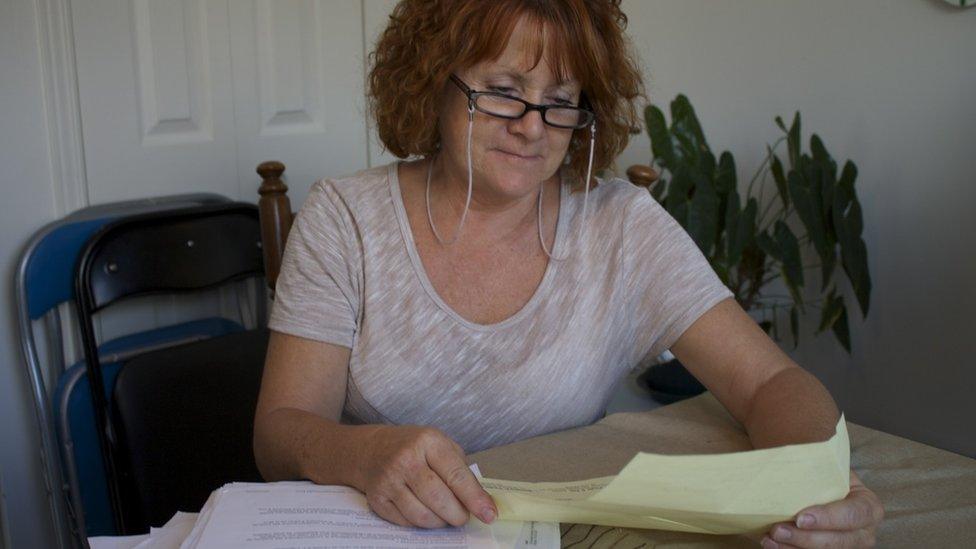

Redheaded grandmother Angele Grenier doesn't look much like a criminal, but she is one of Canada's most wanted women.

And as such, she faces the likelihood of lengthy jail time, and fines of about 500,000 Canadian dollars ($368,000; £245,000).

Her crime? She's a self-confessed smuggler and illegal dealer, someone who sells contraband across province lines.

But what exactly is she selling that has so incensed the Canadian authorities, and seen the police search her property? Drugs? Guns?

Nope, maple syrup - the lovely, sweet stuff that you pour on your breakfast pancakes, or add to your biscuit recipes.

Welcome to the world of maple syrup production in Quebec, Canada's largest province.

'Mafia'

Mrs Grenier and her husband have been producing maple syrup at their farm in the village of Sainte-Clotilde-de-Beauce, 100km (60 miles) south of Quebec City, for decades.

Every spring they bore holes in their maple trees, and drain off the sweet sap. The sap is then boiled down to make the syrup. Nothing is added - it is a completely natural product.

Angele Grenier could be facing a jail sentence

It is a practice that is replicated across Quebec, whose 7,300 maple syrup producers - mostly family-run farms - produce 70% of the world's supply, worth more than 600m Canadian dollars.

The joke is that Quebec is the Saudi Arabia of maple syrup production, such is its dominance of the global market.

The problem for Mrs Grenier, and Quebec's other so-called "maple syrup rebels", is that they cannot freely sell their syrup.

Instead, since 1990 they have been legally required to hand over the bulk of what they produce to the Federation of Quebec Maple Syrup Producers (which in French-speaking Quebec is abbreviated to FPAQ).

Backed by the Canadian civil courts, the federation has the monopoly for selling Quebecois maple syrup on the wholesale market, and for exporting it outside the province.

Producers are only allowed to sell independently cans of less than five litres or 5kg to visitors to their farm. According to the FPAQ, those sales represent 10% of the total sale of maple syrup in Quebec.. Producers can also sell to their local supermarkets, but then they have to pay a 12 cents per pound commission to the FPAQ.

For many Canadians and Americans, maple syrup is essential with their breakfast pancakes

"We don't own our syrup any more," says Mrs Grenier, who calls the federation the "mafia".

Unwilling to put up with this state of affairs, Mrs Grenier and her husband have in recent years been selling their maple syrup across the border in the neighbouring Canadian province of New Brunswick.

In scenes that could come from a Hollywood drugs movie, they load barrels of syrup on to a truck as quickly as possible, and then race it over the border line under the cover of darkness.

The couple are breaking the law, but say they are fighting for the right to sell their syrup for a price - and to customers - of their own choosing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the FPAQ has taken a very dim view.

Making maple syrup in "sugar shacks" such as this one, is a long-standing tradition in Quebec

FPAQ security staff and police officers have paid her a number of visits, and Mrs Grenier is facing prison if she continues to refuse to turn over her syrup.

The federation has also hit her with a 500,000 Canadian dollars fine, which she is now contesting, as she says she won't back down.

"We want our freedom back," says Mrs Grenier.

'North Korea'

Paul Roullard, the FPAQ's deputy director, defends the federation's actions.

He says: "People who say that our practices are totalitarian should go see what happens in China, North Korea, or Africa."

The federation has put tamperproof seals on Mrs Grenier's barrels of maple syrup

Mr Roullard is also quick to point out that the FPAQ didn't unilaterally award itself its powers, rather that they were agreed by "100% of the delegates who represent Quebec's producers, when we voted them [in]".

Back in 1990 when the federation got the first of its far-reaching powers, Quebec's maple syrup producers supported the move because then prices were low, at roughly $1 per pound.

In return the FPAQ promised to market the syrup better, and set prices with authorised buyers. And in this it succeeded, with demand and prices starting to rise to today's 2.85 Canadian dollars per pound levels.

In 2004 the federation again stepped in to help members when a boom in production meant there was a big surplus of unsold syrup.

Mrs Grenier has been fighting a long legal battle

To solve the problem, members backed its decision to impose production quotas on producers, which continue to this day. Any syrup produced above a farm's quota is put in the federation's reserves, where it is kept back to maintain supplies in years when there is a poor season.

At present about 15% of a producer's annual syrup goes into the reserves, with payment not made until it is sold a few years down the line.

The FPAQ says the majority of its members continue to back its policies, such as Raymond Gagne, whose family has been producing syrup for generations.

The 75-year-old says: "The federation is an excellent system, thanks to which we know how much our production is worth before the harvest. Prices are stable and increase every year."

'Communist'

Yet the rebels continue to complain about what they see as the federation's heavy-handed tactics, such as Daniel Gaudreau, a producer from Scotstown in southern Quebec.

He says that in 2014 the FPAQ accused him of selling more than his allotted quota, and so seized his entire production. This year, he says, the federation even posted private guards on his property, and is now suing him for more than 225,000 Canadian dollars.

Quebec produces more than 600m Canadian dollars worth of maple syrup per year

Mr Gaudreau says: "The situation is completely ridiculous. Only a few of us dare to fight the federation because it built a system based on fear, and it has much bigger financial resources than us."

Benoit Girouard, president of Quebecois farming union Union Paysanne, says the FPAQ needs to loosen its rules and methods.

"The federation doesn't have to be as coercive as it is now," he says. "Its system is totalitarian and communist. Producers don't have space to work, that is why most of them cheat."