US rate rise: Why it matters

- Published

Lift off! For the first time in ten years the US Federal Reserve has raised interest rates.

As expected rates were increased by 0.25% to a range of 0.25% to 0.5%.

For almost a decade money has been cheap - some would argue too cheap. But today's rise in US interest rates could be the beginning of a new era, one in which the cost of borrowing rises - possibly for years.

So should we cancel Christmas, buy some tinned food and hide in the cellar, or shrug and return to our online shopping?

Let's take a look at what, and who, might be affected by the expected increase.

Why it matters for the US economy

A rate rise can be seen as a vote of confidence by the Federal Reserve in the US economy.

US unemployment has fallen to 5% - the lowest level in seven and a half years and the annual growth rate is running at a robust 2.1%.

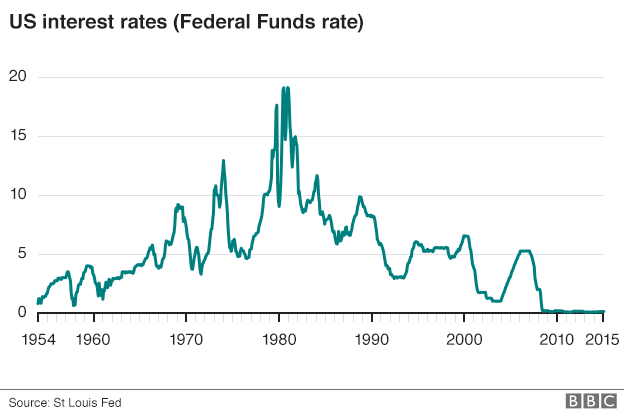

But despite those healthy indicators, interest rates are at emergency levels. Between September 2007 and December 2008, external the benchmark Federal Funds rates fell from 5.25% to between zero and 0.25% in an effort to stave off recession.

Economists argue it is high time rates started to head higher, to prevent excessive consumer borrowing and prevent bubbles emerging in the housing market and other types of assets.

There is some concern over companies that have borrowed too much. Rising interest rates could make it more expensive or impossible for them to refinance their debts.

In particular fracking firms, which produce oil and gas, have been under scrutiny by investors. Not only do they tend to borrow quite heavily, they are also exposed to the falling price of oil. Rising interest rates could see failure rates among such firms rise.

Why it matters for US consumers

The effect of the first rise in interest rates on US consumers is likely to be muted. There are a few reasons for this.

A 0.25% rise is fairly modest and in the short term the cost of borrowing will not rise by much.

Also American households are less in debt than before the financial crisis. According to the New York Federal Reserve overall household debt remains 5% below its peak in 2008.

And US home owners are less sensitive to moves in interest rates as mortgage rates are usually fixed over 30 years.

Nevertheless the extended period of low interest rates has fuelled rising house prices, record car sales and expansion in credit card debt.

Rising interest rates should cool conditions in those hotter markets.

Why it matters in emerging markets

There are a number of circuits in the global economy which link what happens at the US Federal Reserve building in Washington, with countries that have developing economies like China and Brazil.

An era of rising US interest rates is likely to strengthen the dollar. That could cause pain for companies and countries that have raised debt in dollars. If they earn much of their income in a local currency, then servicing a debt in dollars will become more expensive as the dollar rises.

Rising US interest rates affects how investors view risk. If they can earn a more attractive return on investments in the US, they might shun investments in far-flung and riskier nations.

So companies and governments in the emerging world could find it harder to attract investment, or refinance existing debts.

Finally, higher interest rates also come at a bad time for many emerging economies, particularly those that rely on exporting commodities. The price of oil, metals and agricultural commodities have fallen dramatically.

So companies and governments could face higher borrowing costs at a time when earnings from mining and agriculture are falling.

The view from Africa: Matthew Davies, Africa Business Report

The rise in US interest rates is another cloud in what is rapidly becoming a perfect storm for many African economies.

Though widely anticipated, the increase in the Federal Funds rate triggered yet another fall in value of Africa's most widely traded currency, the South African rand.

In an effort to mitigate the inflationary effects of their falling currencies, Africa's central banks have been raising interest rates, which in itself can limit economic growth.

But the Fed's move really means a reversal of the flow of cheap money. Over the past few years, so-called "hot money" has been looking for decent rates of return and billions flowed into Africa.

Now many African governments are lumbered with large dollar debts and a reduced capability to service them.

The past year has also seen big falls in commodity prices as demand from China has slumped.

The persistently low oil price has been hampering the national budget's of Nigeria and Angola.

If this perfect storm gets much worse, it could be a bleak 2016 for several African economies.

Why it matters for the currency markets

The currency markets are extremely sensitive to moves in interest rates. The US dollar has already been rising in anticipation of higher interest rates.

Against a basket of other currencies the dollar is up almost 4% since October, when the chair of the US Federal Reserve Janet Yellen indicated that rates could head higher in December.

Economists are not sure how much further the dollar will strengthen and much depends on the Fed's actions over the coming months.

The effects of the stronger dollar can already be seen in the earnings reports of US companies. Many have blamed weaker profits on the strength of the dollar, which erodes the value of sales made overseas. It also makes their exports less competitive on the international markets.

Why it matters for the UK

The Bank of England denies that its own decisions on interest rates track those of the US Federal Reserve.

However, economists say that now the Fed has moved higher, it will make it easier for the Bank of England and its chief Mark Carney to raise rates as well.

The UK economy is arguably in even better condition than its US counterpart and many economists say that a rate rise is long overdue.

If the Bank of England follows the Fed, then the pound could rise too, particularly against the euro. That would be painful for many British exporters, as the European Union is the biggest market for British goods.

- Published24 November 2015

- Published4 December 2015