Jobless in Germany: Migrants' next challenge

- Published

Chikezie says he is proud of the products his firm makes: "It's light, it's strong and it's quality!,"

A quick glance at the street names in Ottobrunn - Willy Messerschmitt Strasse, Hugo Junkers Strasse - is enough to identify the Bavarian suburb as the home of aeronautical engineering in Germany.

Aviation giants from across the globe occupy grey, heavily-guarded industrial estates, with smaller, specialised firms dotted around the edges.

Nestled among them is Munich Composites, a fast-growing, typical middle-sized "Mittelstand" company, producing carbon-fibre components for anything from gym equipment to racing bikes.

Most of the company's employees are highly-trained graduates of local universities, but the sophisticated machinery still requires manual operation and supervision, and filling these roles has proven rather difficult.

"In the Munich region we almost have full employment," says commercial director Martin Stoppel, "it's not that easy to find people".

Formidable hurdles

Which is why Mr Stoppel was delighted to be approached by jobs4refugees.org, an initiative run by a couple of local volunteers, with the aim of matching some of the many thousands of migrants housed in nearby camps with employers.

Soon afterwards, after wading through quite a bit of paperwork, Chikezie, a Nigerian asylum-seeker who used to work as a car mechanic, became Munich Composites' newest employee.

"I was very very happy because it's not easy [to get a job]," he says. "A lot of people say I am very lucky because I do not belong here, I got a job easily, and the way I work with them, everybody here is so good and kind to me, so it's a kind of joy... I'm happy."

Germany's housing deficit

800,000

New homes needed, largely due to mass migration

260,000

Homes currently built in Germany every year

-

€280bn Cost of building 800,000 homes

Unfortunately, this happy union is rather rare.

Of the million migrants to have arrived in Germany in 2015, the vast majority are aged between 18 and 35, and most are eager to work in their newly-adopted country.

But besides the obvious language barrier, they face formidable hurdles.

"We don't allow refugees to work in Germany," says Prof Gabriel Felbermayr, the director of Munich's Ifo Centre for International Economics.

"We put them into a system where the state has to care for them entirely."

Asylum seekers in Germany are prevented from working during their first three months, and even once they are given a permit, the law gives preference to German or European Union applicants.

After 15 months, this rule expires, but various municipalities impose further bureaucratic obstacles - all of which scare some employees off.

However Robert Barr, who runs jobs4refugees.org, says the biggest challenges for jobseekers are cultural.

Germany's new workers

330,000*

Migrants entering labour market in 2016

660,000*

Migrants entering labour market in 2017

-

130,000* Jobless migrants in 2016

-

200,000* Jobless migrants in 2017

"The problems that arise for the refugees in finding work might seem very small to someone who grew up in a western European country," he says.

Understanding what to expect in a German job interview, for example.

"Basic things like being on time and a firm handshake, which might seem trivial, are quite important to some employers."

Housing challenge

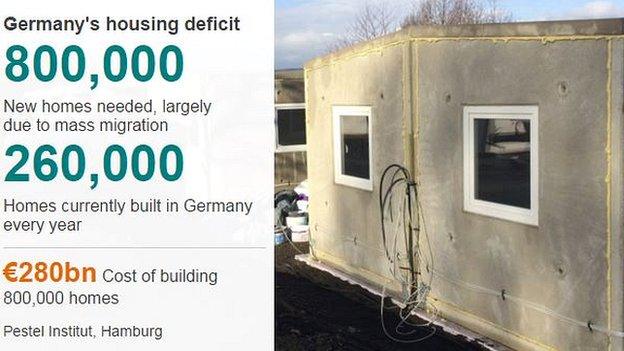

Another hurdle is housing. Even before the influx of migrants in the latter half of 2015, Germany was lagging behind in home building - lacking 260,000 houses.

Now, according to the Pestel Institut in Hamburg, some 800,000 extra homes need to be built. Even suppliers of temporary containers have run out of stock.

"In the Munich region we almost have full employment," says commercial director Martin Stoppel

More importantly, the housing crisis is most acute around major cities like Berlin, Munich and Hamburg - which is also where many of the jobs are.

Despite such pressures, Prof Herbert Bruecker, of the Institut for Arbeitsmarkt in Nuremberg, is cautiously optimistic about the fate of migrants arriving in Germany, and the country's economy.

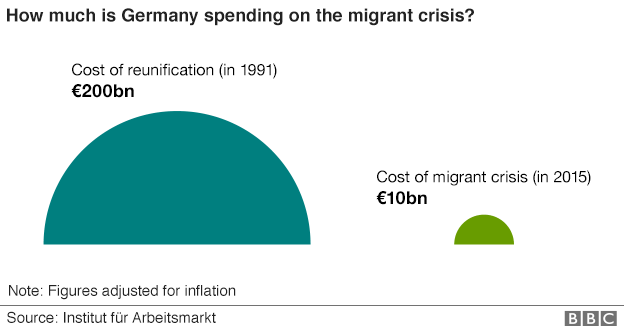

For a start, he points out that the entire cost of the migrant crisis to the public purse in 2015 - estimated between €10-21bn (£7.2-15.2bn; $10.8-22.6bn) - is still a fraction of the €200bn the country spent on re-unification in 1991 alone.

What's more, Germany's overall unemployment rate "will further decline or remain stable at the current level" in the coming few years due to the overall health of the labour market - despite the number of unemployed refugees, he argues.

The urgency, therefore, should be directed towards providing migrants with vital skills, such as learning the language.

"The German labour market is relatively closed, and without German proficiency your labour market prospects are extremely poor," says Prof Bruecker.

Indeed, his boss, the well-known German economist Joachim Moeller, recently warned that "every euro not invested in integration and education" would in the end cost the country several times more, due to social costs and long-term unemployment.

Integration

One particularly successful model can be found just a few hundred metres away from the grounds of Munich's Oktoberfest.

Learning how to say it in German; A language class at Munich's adult education centre

Here a dozen or so women are sitting in a classroom and chanting the German words for everyday ailments: Kopfschmerz, a common headache; Durchfall, dreaded diarrhoea.

When one participant has to resort to miming a stomach condition, having forgotten how to say it "auf Deutsch", her classmates erupt in sympathetic laughter.

All have recently migrated to Germany, and are taking part in what is officially known as an "integration course".

It's a state-subsidised initiative designed to equip those planning to settle in the country with language skills, and much more besides.

"I had a letter from my daughter's school and I didn't understand it," says Anna, who has come from Romania, "and the teacher helped me read through it and respond".

Others students - who hail from a total of sixteen different countries - talk of the help they have received in navigating Munich's increasingly inaccessible housing market, getting medical insurance and job hunting.

"In Germany, it's very common to have to fill in forms for everything you apply for," explains Heidemarie Schmeller, who has been teaching the course for 14 years.

"We try to inform them about as many practical things as possible. They can always ask about anything, and I try and give as much information as I can about living here, about the ways of Germans."

Ms Schmeller is one of 120 German teachers at the Munich's adult education centre, which she says is the biggest of its kind in Europe.

But the teacher, whose only concession to didacticism is in instructing her students to share her love of the Bayern Munich football team, admits she is worried about pressures on the centre as demand for courses increases.

"Our classes are full now. We need teachers now, and we have special qualifications, not only in academic study, but a special three month preparation course for integration classes"

"Where can we get teachers, and rooms, and equipment - that's one of my worries".