Is the world's art market cooling down?

- Published

The Lock by John Constable didn't fetch the price Sotheby's had hoped for

It is a rainy December evening in London and Sotheby's is holding one of its last major auctions of 2015 - a sale of works by Old Masters from the Renaissance era and works by British artists such as John Constable and Joseph Wright of Derby.

The bidding is slow and stuttering. "All that wait for nothing," mutters the auctioneer as a telephone bidder thinks long and hard about a making a higher offer before changing his mind.

Most works sell at the low end of their estimated price range. Constable's The Lock, for instance, fetches $13.5m (£9.1m) when it was estimated to sell for as much as $17.8m.

It is an oddly subdued end to the year, because the headlines in the media were suggesting that in 2015 the art market caught fire.

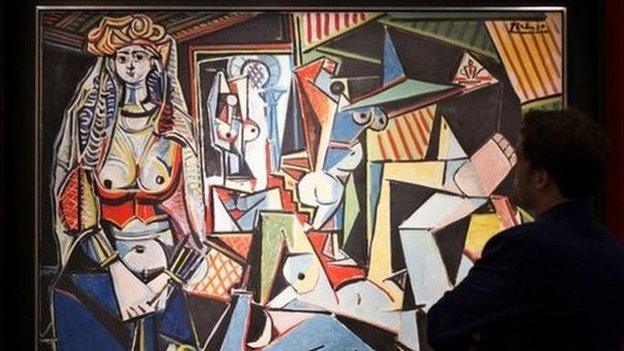

In May, Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger, Version O, sold at Christie's in New York for $179.3m (£120.6m). Bidders in the auction room erupted in applause: it is the highest price ever paid for a work at auction.

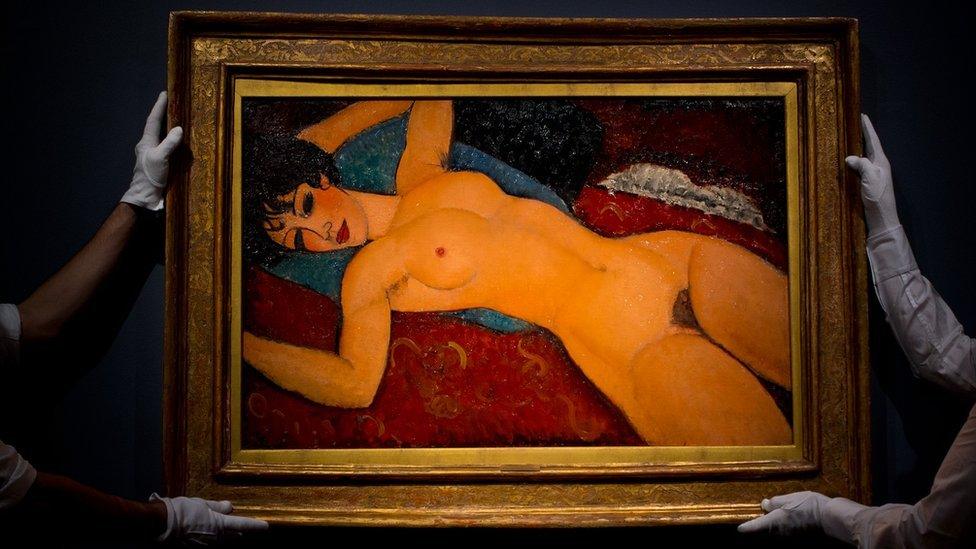

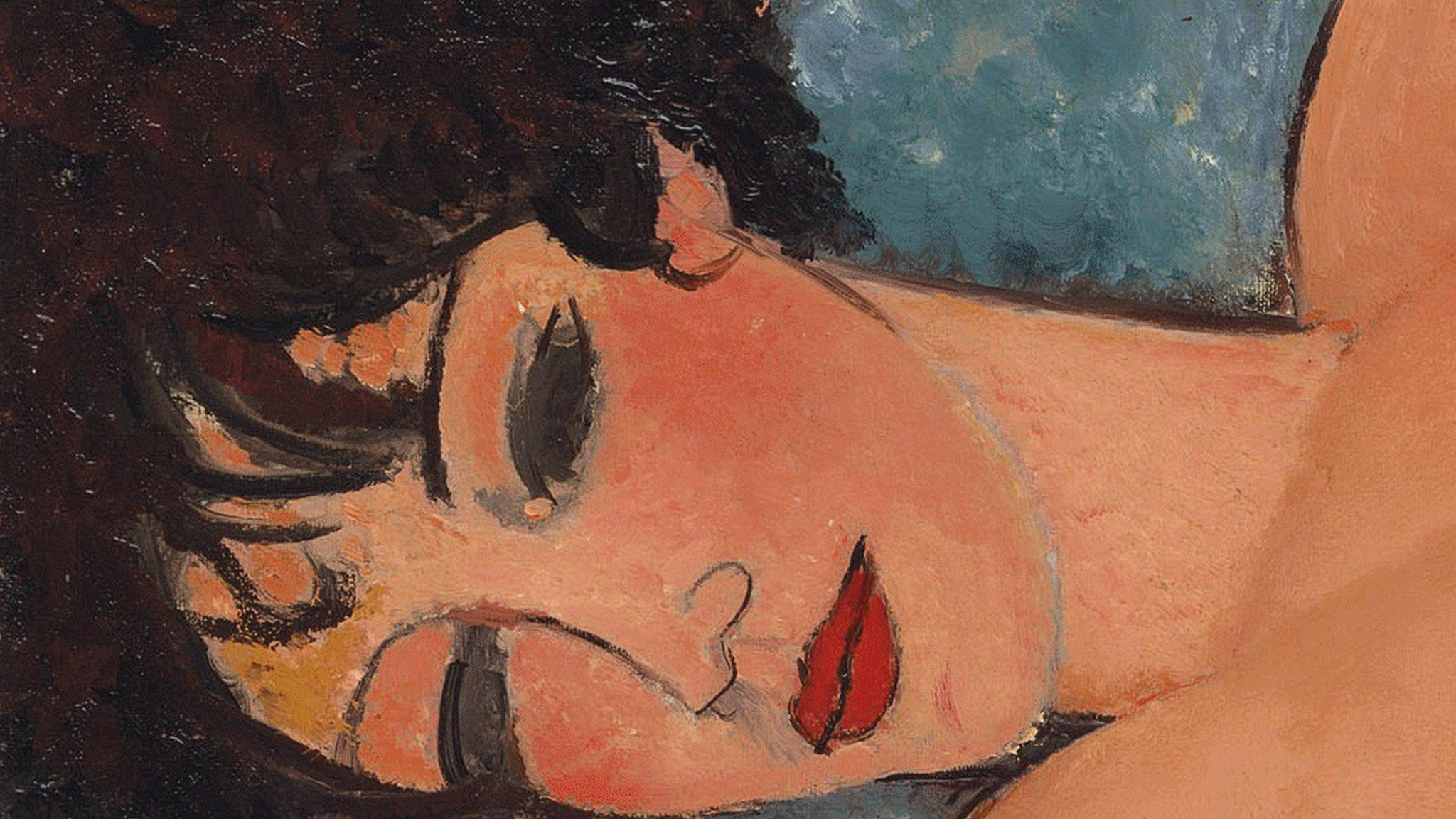

Then, in November, a Chinese businessman paid $170.4m for Modigliani's Nu Couche (Reclining Nude) - the second-highest price ever fetched at auction.

'What am I bid?' The auctioneer opens proceedings at the sale of Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger

The auction saw intense phone bidding

And the painting sold for a record breaking final price of $179.3m

However, 2015 also saw seen many auction flops. Claude Monet's Nympheas sold for $33.8m, well below its top estimate of $50m and Andy Warhol's Four Marilyns sold for $36m rather than the expected $40m.

It seems that many of the world's millionaires are now feeling worried about the future, and are opting to keep their wealth in cash.

This is particularly true of rich Chinese, who now make up a fifth of the world's buyers of art.

Turbulence on the Shanghai stock exchange in 2015, an economic slowdown and tough anti-corruption laws have persuaded many to stop splashing out on art.

"At the very, very top of the market - amongst billionaires who are really keen to get a great work by a really famous-name artist like Picasso - there is still a lot of competition", says Jane Morris, editor of The Art Newspaper, based in London.

"Once you go under that, where we're talking prices in the millions of dollars, people are feeling more squeezed.

"There's much less confidence in the Chinese market. The Russians are feeling much poorer. People in general are feeling poorer, and that has had an impact."

Modigliani's Nu Couche didn't disappoint, a Chinese businessman paid $170.4m for it

The biggest impact of all has been on the market for contemporary art, which had been booming for five years or more and where prices had been surging.

This autumn, Christie's made only $331.1m from its post-war and contemporary art sale. That is well below the $852.8m made from the same event in 2014.

And Christie's Asian 20th Century and contemporary auction, held in November in Hong Kong, made only $66m compared with $82m made at a similar event in 2014, and $121m in 2013.

People who buy art as an investment now appear to be switching away from contemporary art towards old masters and well-known painters from the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Works by "brand-name" artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Paul Gauguin and Gustave Courbet all fetched record prices at auctions in 2015.

Many Chinese buyers, such as Liu Yiquin - who bought Modigliani's Nu Couche - are now buying Western art at auctions in London and New York rather than contemporary art in Hong Kong.

Art Basel Miami is an event held in December where people in past years, have spent millions of dollars on contemporary artworks within a few hours of the galleries opening for trade.

This year, said the organisers, people were much more circumspect and buying was far less frenzied.

Buyers appear to be spurning newer artists and sticking with well-known names such as Roy Lichtenstein

Peter York, a London-based consultant on brands, fashion and the arts, says he is relieved that the market for contemporary art is now on the wane, because he thinks many artists have been oversold by art critics and commentators.

"People have been advised by curators: here's an upcoming person," he says. "They take the word of these curators that 'upcoming' means 'growing in value'.

"Once they stop believing in that, they follow their hearts. It's easier to see the joy in an old master, and you think: those are a solider asset class."

The biggest challenge of this cooling of the art market may be for the auction houses, such as Sotheby's, Christie's and Bonhams.

In the struggle to be the one which sells the most prestigious works, they often give the vendor a guaranteed price. If the bidders fail to reach that price, the auction house buys the work.

This has, arguably, artificially buoyed prices. However, if the art market continues to cool in 2016 and auction houses continue to underwrite the price of works, they may end up with a lot of unsold art in their vaults.

- Published10 November 2015

- Published12 May 2015

- Published22 July 2015