Unstoppable force? The earning power of Star Wars

- Published

A LOT of things get blown up in any Star Wars film, and The Force Awakens is no exception. But of all the things that get smashed, the box office has been as wrecked as any poor Imperial tie-fighter.

The list of records being set by this film is dizzying. The biggest opening weekend in American history, the biggest four-day total and the record time to gross $300m (£202m). Jurassic World had reached that mark in eight days; The Force Awakens got there in five.

Here in the UK, it took £9.68m on its first day and a smidgeon under £40m over its first five days on release. And yes, both of those are records, along with a plethora of other figures from all over the world. This is a film that is earning money at a remarkable pace.

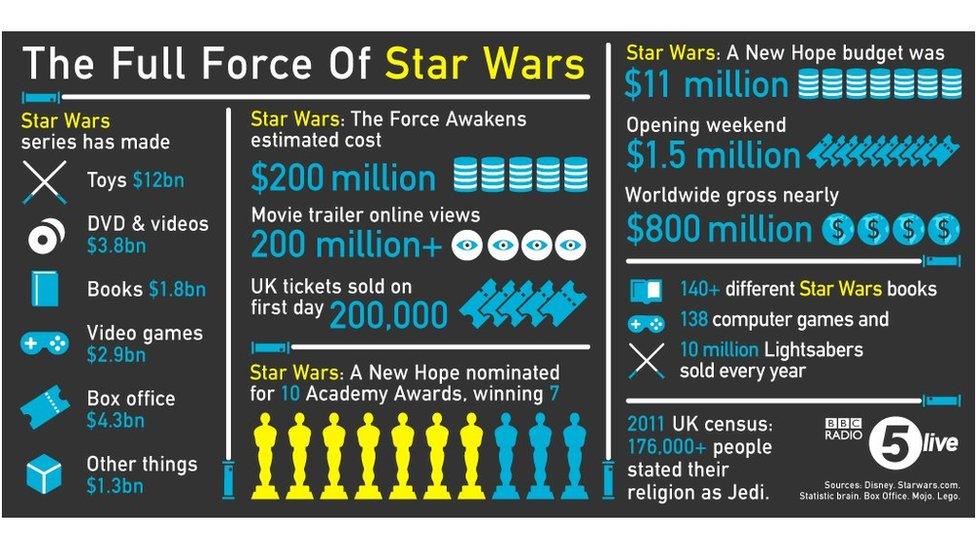

And are we surprised? Of course not. This might be the first Star Wars film for a decade, but the Star Wars machine has never stopped working - bolstered by toys, games, cartoons, books, theme-park rides and bundles of merchandise. Since the first film came out, this franchise has generated more than $30bn in revenue, making it the most lucrative entertainment franchise in the world, but only a third of that has come from the films. The rest has all been down to merchandising. And that's how Star Wars changed the world.

There are shelves of merchandise in toy shops

At this point, let me make an admission. I'm a Star Wars fan, and I have been since I was a boy. I was seven years old when the first film came out and fascinated me; three years later I saw the Empire Strikes Back, with which I became almost instantly besotted. And after that, Even the Phantom Menace didn't spoil my enthusiasm.

Now I have a 10-year-old son of my own, who's watched these movies with me. But he's also played the computer game and built endless Lego Star Wars models, so with the Force Awakens coming to our screens, it seemed a good time to make a programme about the business of Star Wars.

It all started with George Lucas, of course, coming up with a story called The Adventures of Luke Starkiller, as taken from "The Journal of the Whills". Starkiller became Skywalker, the "Journal of the Whills" was dropped from the film and so the title became simply Star Wars. But neither Universal nor United Artists wanted to make the film, and even 20th Century Fox were a bit unsure. So Lucas did a deal to ensure his film got made - he'd get paid a much smaller director's fee, but would get the film's commercial rights instead.

Elstree: The stage set for Star Wars

Fox weren't worried - film merchandise had rarely sold well, and the studio still had a warehouse full of Doctor Doolittle trinkets that nobody wanted. So Lucas got to make his film, hoping to make back the budget of $11m.

But along the way, a man called Bernard Loomis heard about Star Wars. He worked for Kenner Toys, notable for their Six Million Dollar Man action figure. When the film came out, he signed licensing deals with both Fox and Lucas, and discovered an incredible demand for toys from the film. Action figures sold out almost immediately, leading the company to sell empty boxes that just contained a gift token promising the bearer a figure when they came out again. And the empty boxes sold out, too.

The original Star Wars toys from the 1980s are still sold at auction and are sought-after by collectors

Kenner became part of Hasbro, and I spent a while chatting to the company vice-president Jerry Perez.

Star Wars, he says, is still the ultimate toy franchise - appealing to people all over the world, male and female, young and, er, less young. The light saber, says Perez, is "the ultimate toy".

And then there's Lego, a company that was on its knees a while ago. Then it started producing Star Wars Lego, and the finances were reversed so spectacularly that Lego is now, by some measures, the biggest toy company in the world. For my programme, I spoke to the man who first thought of Star Wars Lego, and is still designing it to this day. It's so important to the franchise that he gets to visit the set, discuss the design of top-secret X-wings and Star Destroyers, and then decide which actors to turn into mini-figures.

Then, of course, there are the film studios. Star Wars was filmed at Pinewood; Harry Potter was made up the road at Leavesden. The British film industry, once in the doldrums, finds itself in such rude health that Lucas's Industrial Light and Magic company now has a base in London. We have movie technicians to rival the best in the world, and we also have a tax regime that helps filmmakers.

Hallowed ground: the George Lucas stage in Elstree

And so, 40 years after Lucas made that gamble with his fee from 20th Century Fox, we can safely say it's paid off. He sold his company to Disney for just over $4bn a couple of years ago, but few doubt that Disney will make its money back.

Two more Star Wars sequels are in the pipeline, as well as three other spin-off films. And while Avatar's all-time box office record of $2.7bn is still a long way off, few would bet against The Force Awakens getting there in the end. But that's only part of the story - remember the Lego, the toy light sabers, the duvet covers, DVDs and books. The Star Wars business empire sprawls a long, long way.

You can hear Adam's documentary on Radio 5 live here.

- Published23 December 2015

- Published22 December 2015

- Published16 December 2015