How Prince Philip helped save British engineering

- Published

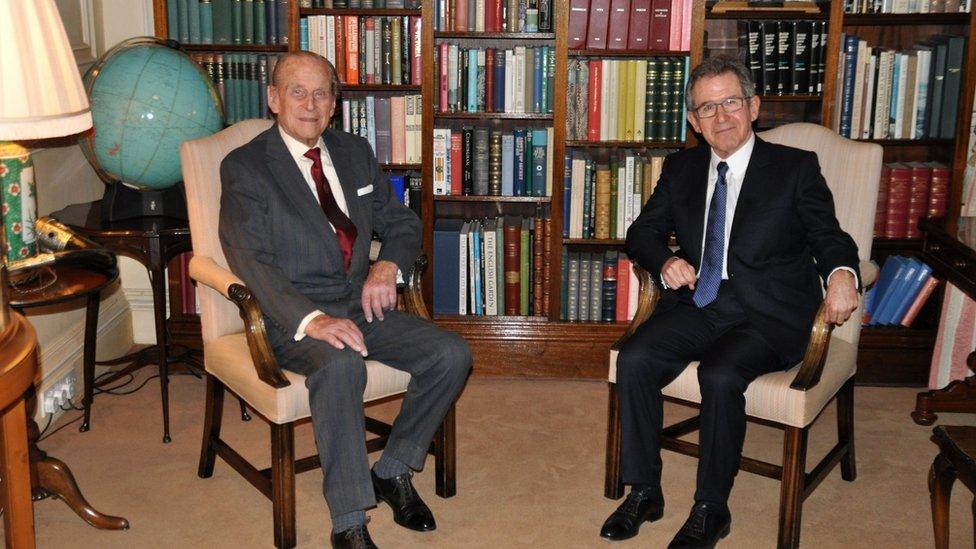

Prince Philip and Lord Browne

Prince Philip helped save engineering in Britain in the 1970s. He was a key mover in the creation of a national engineering academy, and his love of engineering remains undimmed, writes Today programme guest editor Lord Browne of Madingley.

"Everything that wasn't invented by God is invented by an engineer," HRH Prince Philip certainly has great experience in setting the framework for a conversation.

And that's exactly what he did as I sat down for my interview with him in December for Radio 4's Today programme. His views are clear, forthright and, as usual, to the point.

When I asked him about innovation, he tells me that engineering is the only way to make new ideas relevant.

When he talks of our planet he says that, in an increasingly crowded world, engineering is the only thing that can maintain the balance between nature and human ambition.

Making things better

When I ask him about the comprehensive nature of modern engineering, he says that you only need to look around you to see how it has made new things and solved natural problems.

And when it comes to young people - who seem to start life as natural engineers not least by taking things apart, as I did when I was young - he points to their desire to make things better.

That is how he would describe the purpose of engineering: to make things better.

John Browne - Lord Browne of Madingley

He is currently executive chairman of L1 Energy and was previously CEO of BP from 1995-2007, transforming it into one of the world's largest companies

He is a fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering and was president from 2006-2011

He is a fellow of the Royal Society, was awarded the Prince Philip Medal in 1999, and is currently chairman of the Queen Elizabeth Prize Foundation

He was knighted in 1998 and made a life peer in 2001

'Dull, without innovation'

Prince Philip recalled that after the war the UK was "completely skint. It seemed to me that the only way we were going to recover was through engineering".

In the 1960s it seemed to me as a young man entering Cambridge University that engineering, and the related activity of manufacturing, were well past their prime.

As undergraduates, many of my fellow students and I thought that engineering was dull, set in Victorian times, run by the book without much innovation, and with little to offer as an exciting career prospect.

The excitement was confined to transistors, nuclear reactors, new oilfields and rockets.

These things seemed far away from the thought and behaviour of the professional institutions which gave engineers their licence to practice.

As a student, Lord Browne says he thought engineering was dull, "set in Victorian times"

National academy

So I studied physics and then became a petroleum engineer only to find that this form of integrated engineering was not recognised by any institution; at least not then.

Meanwhile Prince Philip, using his "soft power" and several dinners at Buckingham Palace, began to put together the engineers from the various professional institutions.

"They hardly spoke to each other," he says.

"Trying to find a way to get engineers to select the best among them," was how he catalysed the formation of the national academy of engineering.

It later became the Royal Academy of Engineering, external, which was given the task of identifying excellence in engineering, and integrating the ideas of engineering across its different disciplines.

After all, history shows that the intersection of specialist activities is where the most interesting contributions are made.

'Critical role'

Prince Philip recognised that the Royal Society, external, Britain's national academy of science, thought it already looked after engineers.

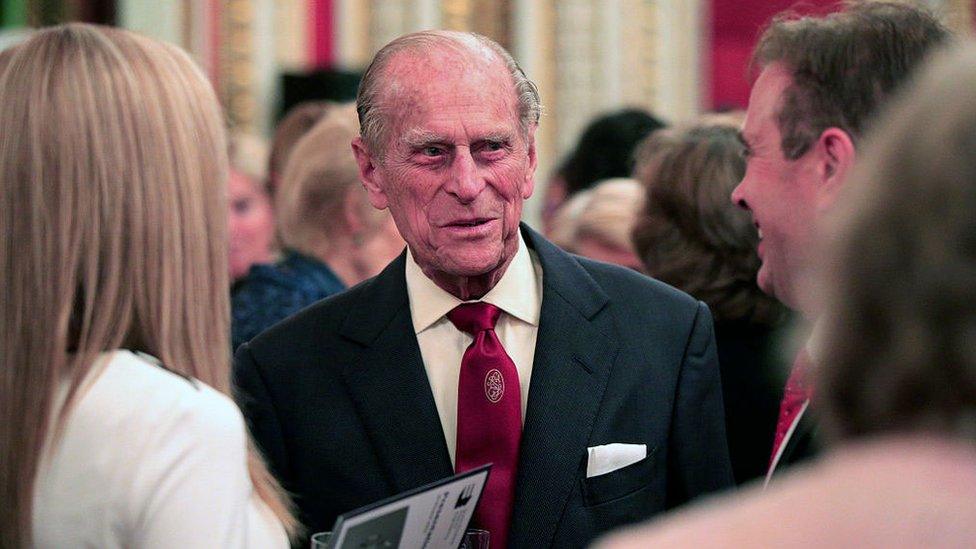

Prince Philip speaking to guests during a reception for The Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering at Buckingham Palace

But patient and far-sighted "wheeling and dealing to soothe people's anxieties" allowed the two national academies to co-exist and to co-operate.

In this way I believe that Prince Philip saved engineering in the UK, ensuring that it has not merely a great history, but a great future too.

Reflecting the critical role he played in its formation, Prince Philip became senior fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering.

While I was president of the Academy, I spent hours talking to him about innovation and engineering and watching his interaction with other engineers.

He always valued the practical and, like all good engineers, he wanted to know how things worked.

In engineering, the most simple solutions are often the most effective, so an engineer would be on dangerous ground if she or he could not give Prince Philip a straightforward answer.

Engineering prize

During my interview I asked him whether he thought that engineers were not treated with the respect that they deserved. He would not let me get away with such a generalisation.

Generalisations, he has often said, are rubbish and he is usually right.

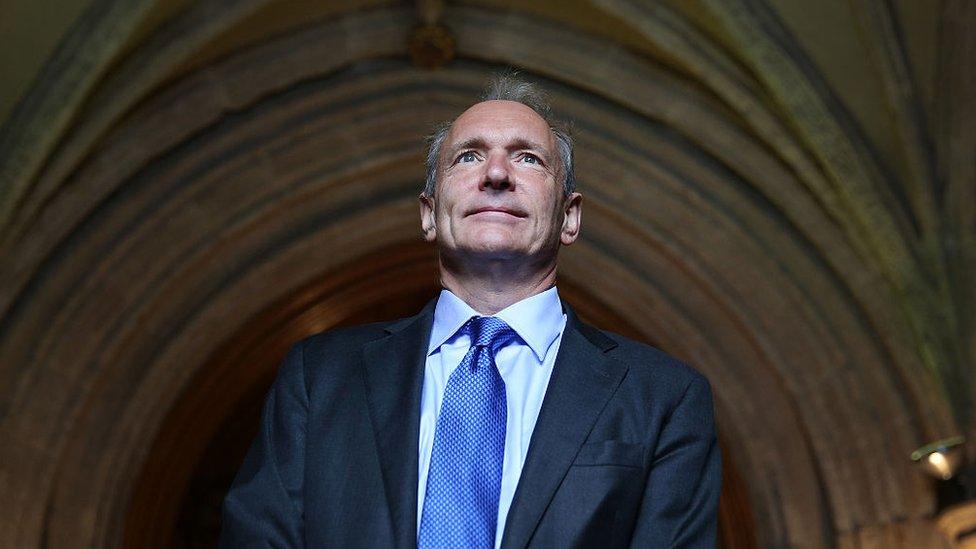

Winners of the Queen Elizabeth Prize have included Sir Tim Berners-Lee for the invention of the world wide web

and Dr Robert Langer for the chemical engineering behind time-release cancer drugs

But there was one important point on which we both agreed: the lack of a Nobel Prize for engineering. I talked about the Queen Elizabeth Prize, the newly established global prize for engineering which I chair, and how I thought it could become the equivalent of a Nobel Prize.

He acknowledged the gap which perhaps is now filled. The Queen Elizabeth Prize has been awarded to a rich array of engineers, from Sir Tim Berners-Lee for the invention of the world wide web to Robert Langer for the chemical engineering behind time-release drugs used to treat cancer, amongst other illnesses.

The prize recipients represent the very best of what engineering can achieve for mankind.

As we started our conversation he talked about engineering and infrastructure, the vital things that make it possible for us to live today.

I thought of my own time as an engineer at BP, trying to bring light, heat and mobility to as many people as possible.

Whatever future challenges we face, "disciplined and thoughtful engineering is needed" argues Lord Browne

Like many over the Christmas period, I have also observed the devastating effect of the recent floods on so many people.

Whatever the challenge - from poverty to disease, and from global communication to global climate change - disciplined and thoughtful engineering is needed.

I am in no doubt that if I had my time again, I would study engineering.

For more from Radio 4's Today programme, including the latest episodes, highlights and podcasts, click here