Believe in this? 'Trust me, I'm a chief executive'

- Published

A small experiment. Which of the following do you consider the most (or least) credible: "Trust me, I'm a doctor", "trust me, I'm an architect", or "trust me, I'm a FTSE chief executive"?

Unfortunately, ample evidence shows that - along with "trust me, I'm a journalist" - the final example of the businessman is met with widespread disbelief.

The financial crash of 2008, although originating in financial services, did immense harm to trust in businesses across the board.

Decency, fairness and plain-dealing - doing "the right thing" if you like - appear often to be in short supply.

Many have found it hard to escape the conclusion that business is there just to maximise shareholder profit while pulling the wool over all our eyes.

'No impact'

The first stop on my trust in business odyssey for BBC Radio 4's In Business programme was Ingolstadt in Bavaria, the home of Audi, which is part of the scandal-hit VW group.

There I was granted an audience with Audi's chairman Rupert Stadler. Despite everything - the latest blow being a $20bn (£13bn) lawsuit from the US government - he appeared surprisingly optimistic on his corporate naughty step.

Audi chairman Rupert Stadler says he is "absolutely convinced made in Germany still has a high value"

While acknowledging that some very serious things had gone wrong, customers had been let down, and things had to be "cleaned up", he was confident in his company's long-term future.

"There will be a slight short-term reaction in markets. A little insecurity. In long run no impact," he says.

I sensed Mr Stadler was keen to create some clear blue water between his premium, high-margin Audi brand and the VW mothership.

Neither did he think the good name of "made in Germany", the premium that can be added to manufactured goods made in that country, would be affected by the reputational fallout.

"All those comments are exaggerated. I'm absolutely convinced 'made in Germany' still has a high value."

Honesty, integrity and transparency

At the other end of the trust scale sits the British John Lewis Partnership comprising the John Lewis department stores and the Waitrose supermarkets.

John Lewis founder Spedan Lewis topped a BBC poll of the UK's most admired business leaders

Its chairman Charlie Mayfield says: "I think trust means three things. Firstly, act in the customer's interests.

"Secondly, make sure you always do as you say you will, and thirdly, if something goes wrong - admit it and then deal with the problem."

This combination of honesty, integrity and transparency is no bad yardstick.

"You get a 'trust deficit' when an inherent conflict arises between the making of profit and the interests of the consumer," says Mr Mayfield.

"At the extreme these two can be in opposition. So maximisation of profit is not our goal. We aim to make sufficient profit."

Trust shift

The annual Edelman Trust Barometer, which measures trust across the business world. is announced the week after next at the World Economic Forum at Davos. Trust levels have been down across the board in recent years.

Edelman, a global PR consultancy, used to be run in the UK by Robert Phillips, who has recently written a book entitled, Trust me, PR is Dead.

"Trust is the most abused word in the business lexicon," he says. "Trust is not a message to be sold by PRs, it is an outcome."

Business has suffered a rough reputational ride in recent years, with many sceptical about the value of business to society

Mr Phillips, a repentant spinner, also thinks corporate social responsibility has had its day, and thinks that concentrating on being "trustworthy" by becoming more transparent and honest is the only way forward for companies if they wish to succeed.

For Rachel Botsman, who teaches at the Said Business School in Oxford, there are signs of hope, however.

She says the rise of the collaborative economy shows that trust can be re-found.

"It's messy, but we are at the start of a profound trust shift," says Ms Botsman.

"Direct business interactions between individuals, such as occur with the French lift-sharing service Bla Bla Car, show that social trust is the new thing.

"This is miles away from the old world of licences, regulation, contracts and top down corporations."

Golden age?

It's become commonplace to say that business is more mistrusted today than ever before. I'm not sure this is true.

Was there ever a golden age of trust? The Victorian era when robber barons ruled the land, and children were put up chimneys and down mines, and Charles Dickens laboured in a boot-blacking factory aged 12?

The 1920s and 1930s were decades of bitter strikes, worker lock-outs, and compulsory wage cuts. In recent decades we had Robert Maxwell, Polly Peck, and Enron.

What is true, however, is that mistrust of business is mostly confined to large companies. It's unusual for people to feel so hostile towards business in their local communities - indeed, if they did these small and medium-sized firms would be unlikely to survive.

There's something about the size that comes with success and growth that engenders trouble on the trust front.

Maintaining clear purpose, engagement among your staff, and your integrity, is undoubtedly far harder once the boss no longer knows everyone.

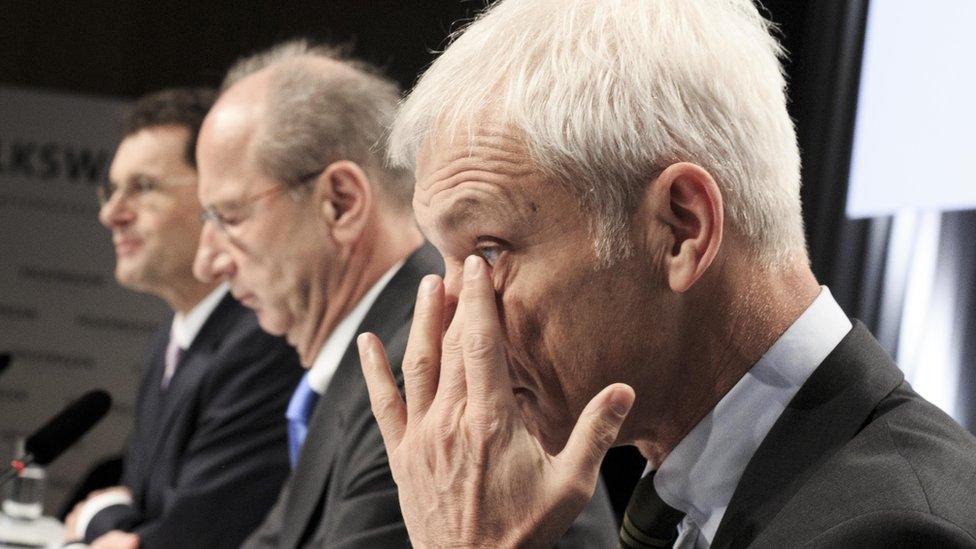

VW bosses Hans Dieter Poetsch (centre) and Matthias Mueller (right) announce the latest update in the company's emissions scandal

Coming back to VW - the group has a long way to go to rebuild its reputation.

Who remembers the classic TV commercial for the Volkswagen Golf from the 1980s, when the model Paula Hamilton leaves her boyfriend, discards her fur coat and ring as she leaves the house, before stepping into her Golf?

The tagline at the end was - "If only everything in life was as reliable as a Volkswagen".

You can hear Matthew Gwyther's episode of In Business - the Business of Trust - at 20:30 GMT on Thurs, 7 Jan 2016 and again at 21:30 GMT on Sun, 10 Jan 2016 on BBC Radio 4. Or you can download the podcast here.