A billion dollar bet: The difficulty of leading a 'unicorn firm'

- Published

A unicorn firm refers to a privately owned tech start-up valued at $1bn (£686m) or more.

BlaBlaCar - a long distance ride sharing platform - was, like many start-ups, invented to solve a simple problem.

Founder and chief executive Frederic Mazzella was trying to get back to his family in time for Christmas, but had left booking his train ticket too late and all the seats were taken.

In the end his sister agreed to pick him up in Paris and drive him the 300 miles to the family home.

On the way, Mr Mazzella noticed how many cars with just one driver were on the road.

"I was like, oh my god... there were thousands of people driving there, and thousands of seats available, but those seats were not in the train, they were in the cars," he says.

After this revelation, in 2006, he launched what has been described as "hitchhiking for the 21st Century" - an online marketplace that connects drivers with passengers who want to go to the same place.

Drivers are allowed to cover reasonable expenses, but not make a profit. BlaBlaCar itself makes money by collecting a transaction fee - around 10% - of the total cost of a journey.

'Struck by lightning'

Its name comes from how much drivers and passengers wish to chat on the way.

The idea has been well received by private investors, with the firm being declared a "unicorn".

The term, coined by venture capital investor Aileen Lee, refers to privately owned tech start-ups valued at $1bn (£686m) or higher.

Ms Lee named them after the mythical creatures because they are so hard to find.

"The odds are somewhere between catching a foul ball at an MLB [baseball] game, and being struck by lightning in one's lifetime. Or, more than 100 times harder than getting into Stanford," she said at the time, external.

BlaBlaCar's founder and chief executive Frederic Mazzella says becoming a unicorn firm is "the beginning"

CB Insights, a research firm that tracks start-ups, calculates there are now 144 such firms globally, cumulatively valued at a whopping $525bn.

The list, external includes some well know start-ups, such as Uber, valued at a staggering $51bn, alongside room rental website Airbnb; mobile photo and video sharing app Snapchat; and Chinese electronics firm Xiaomi. BlaBlaCar, valued at $1.6bn, entered the elite ranking last September.

Chief executive coach and author Steve Tappin says being labelled a unicorn comes with "massive expectations", and that managing a unicorn firm's expansion, with, at some point, the need to make a profit, is a tricky balancing act for their leaders.

Mr Mazzella himself is cautious about the significance of becoming a unicorn, comparing it to celebrating his 18th birthday. "It's the beginning", he says.

For his company, which he says has to be global to achieve the economies of scale it needs to succeed, being described as a unicorn enables people to understand the "huge potential" for the firm's future.

Which way? BlaBlaCar - a long distance ride sharing platform - connects drivers with passengers who want to go to the same place

Controversial?

Mr Mazzella's caution is hardly surprising because, for all the positives, becoming a unicorn firm is also increasingly controversial.

In contrast to a publicly listed firm, whose value is determined by what public-market shareholders are willing to pay for it, a unicorn firm's value often reflects the deal that private investors have secured with its owners.

In many instances investors will agree to a higher valuation for the start-up in exchange for a guaranteed return if the company is acquired or floats on a public stock exchange. Or investors may receive a promise that they will get their money back first if the company fails.

But if and when a unicorn firm finally seeks shareholders on an open market, or a sale, these numbers may not match the balance sheet.

Prezi's Peter Arvi says it was difficult to find funding initially

Well-known Silicon Valley investor Michael Moritz, chairman of Sequoia Capital, recently warned against unicorns on this basis, saying good numbers "seem the flimsiest of edifices".

"For the past three or four years private investors have just been more forgiving than their public market counterparts, who, had they been presented with the most recent financial reports of a good number of these companies, would have decimated the stocks," he wrote in the Financial Times.

Start-up firm Prezi, which is trying to revolutionise the world of digital presentations, and competes with the likes of Microsoft's PowerPoint, has so far avoided the unicorn ranking.

The firm's founder and chief executive Peter Arvai says it simply wasn't possible to attract external investors when he started the company in the depths of the 2008 recession.

"We decided to boot-strap the company. I went without a salary for one-and-a-half years," he says.

Once the product launched, positive reviews meant that investors approached the firm, rather than him being forced to seek out funding.

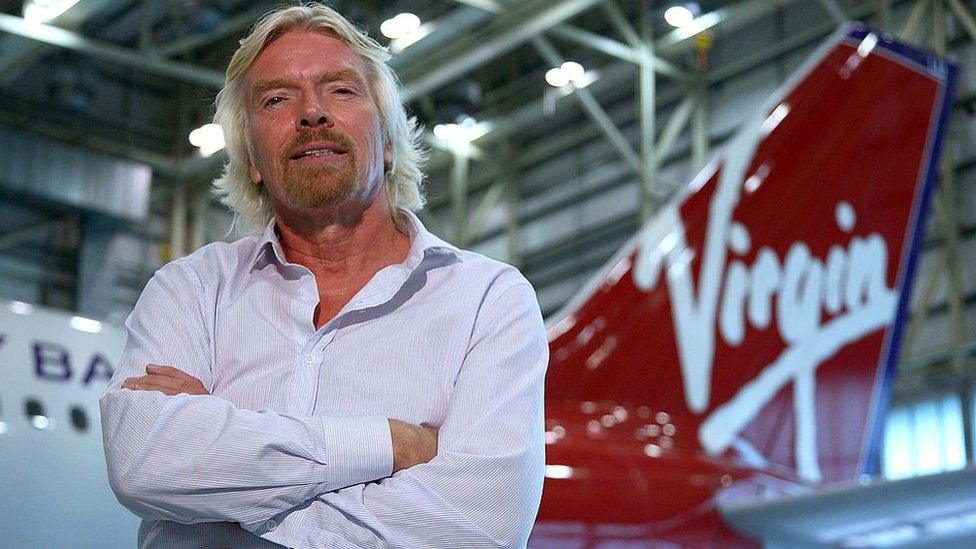

Serial entrepreneur Richard Branson says his main goal was simply to create something he could be proud of

Since then, he says he's often asked whether he would float the firm on a public stock exchange, or sell it, to speed up its expansion, but says ultimately the decision will be determined by what works best for the company to achieve its potential.

"A lot of times questions around valuations and financing becomes a goal in itself, but I actually think it's a means to an end," says Mr Arvai.

"It's important to keep that in mind, I think, if you're building a company for your customers."

'Proud of'

Similarly, entrepreneur Sir Richard Branson, who started several successful businesses under the Virgin name, from airline Virgin Atlantic to Virgin Trains, long before the term unicorn was invented, says valuation never entered his mind in the early days.

"I never ever thought of the fact that one was creating a billion dollar company. I was just wanting to create something I could be proud of.

"If I see something's not being done well I'll dive in there and try to see if we can do it better. And if you do it better then the public will like it, and whatever it is you're creating will be successful," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by CEO coach and author Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig.