Could the dominance of English harm global scholarship?

- Published

Are we "losing knowledge" because of the growing dominance of English as the language of higher education and research?

Attend any international academic conference and the discussion is likely to be conducted in English. For anyone wanting to share research, English has become the medium for study, writing and teaching.

That might make it easier for people speaking different languages to collaborate. But is there something else being lost? Is non-English research being marginalised?

A campaign among German academics says science benefits from being approached through different languages.

Researchers whose first language is not English worry they have to subscribe to Anglo-American theories to get published in major international journals.

Publishing in English

According to the German linguist Ranier Enrique Hamel, in 1880 there were 36% of scientific publications using English, which had risen to 64% by 1980.

But this trend has been further accentuated, so that by 2000, among journals recognised by Journal Citation Reports, 96% were in English.

Is the tradition of German science, with figures such as Einstein, harmed by the shift to English?

Getting published in these recognised journals influences university rankings, which in turn affects funding and recruitment, so there is an incentive for universities to encourage their scholars to use English and the cycle continues.

This trend is reinforced even further as increasing numbers of courses in Europe and Asia are taught in English.

In the Netherlands, Maastricht University offers 55 masters courses in English and only eight exclusively in Dutch. The University of Groningen now uses English as its predominant language for teaching.

In Germany a campaign led by academics, called ADAWIS, wants to preserve German as a language of science.

Academics say many fields of science developed because of different approaches taken by academics using their native languages.

More stories from the BBC's Knowledge economy series, external looking at education from a global perspective and how to get in touch

Professor Ralph Mocikat, a molecular immunologist who chairs ADAWIS, says individual languages use different patterns of "argumentation", the way that conclusions are reached from debate and examining evidence.

He says "the argumentation is more linear in English-language papers, whereas the German grammar facilitates cross and back references".

'Thought is formed by language'

Prof Mocikat says academics often use metaphors from everyday language when making an argument or trying to solve a problem, and these cannot always be directly translated.

"Thought is formed by language. This is why language plays a crucial role in the progress of science," he says.

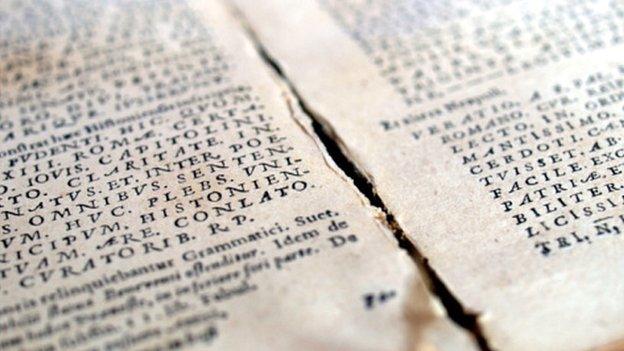

English has become the academic language, a place once held by Latin

"Scientists such as Galileo, Newton and Lagrange abandoned scholarly Latin, which was universal, in favour of their respective vernacular.

"Ordinary language is science's prime resource, and the reintroduction of a linguistic monoculture will throw global science back to the dark ages."

Research suggests that to be published in an English journal, academics generally need to subscribe to Anglo-American theories and terminology.

Professor Mary Jane Curry of the University of Rochester in the US and Professor Theresa Lillis of the Open University in the UK have studied how the dominance of English-language journals has affected research from southern and central Europe.

They found the "gatekeeping" of an English-language journal influenced the content of research, bringing it in line with established Anglophone theories.

'Science history rewritten'

International journals rarely accept quotations and references to papers in other languages, which worries Professor Winfried Thielmann, a linguist at the Technical University of Chemnitz and member of ADAWIS.

"Scientific history is currently being rewritten at the expense of those who had the misfortune of publishing their insights in a language other than English," he says.

Winners and losers: US universities can dominate new academic theories and terms

Prof Thielmann says journals mainly accept papers that use American theories and terminology, which means there is less incentive for researchers to develop alternative ideas in languages other than English.

"In my view this was one of the reasons European economists did not have a lot to contribute to the management of the last financial crisis," he says.

There are concerns that we risk "losing" knowledge because scholars not using English are rarely heard outside their own country.

"Some prefer to build their careers solely domestically, because it is so difficult to master English," says Dr Anita Zatori, at the Corvinus University of Budapest.

"In my experience you need to be able to think in English to speak to an international audience and many people lack either the ambition or the courage to do this."

Lost impact

Good academic translation is expensive and English-language journals would not usually run an article that previously appeared in another language.

There are 6,000 scientific journals in Brazil, mostly in Portuguese, and only a handful are recognised by the international index of journals.

Research from Brazil is often not translated and will lose its impact

Most of this research will not have an impact outside Brazil.

If the rise of English in academia creates problems, what are the solutions?

Journals could become multi-lingual and publish summaries of each article in different languages. The scientific journal Nature provides information about new publications in Japanese and Arabic.

Others have tried to promote linguistic diversity by offering degree courses in more than one language.

The European masters in classical cultures degree, taught by a number of European universities, requires students to attend at least two universities where different languages will be spoken.

Simpler English?

There are even calls to change the English language - or at least the way it is used in articles, books and conferences. The style and tone of articles could made simpler, with concepts framed using concrete examples rather than metaphors which are unique to English.

The English as a Lingua Franca (ELFA) Corpus Project could help with this. It was developed by researchers at the University of Helsinki in Finland and lists one million words of "academic" English to guide researchers.

Perhaps the continued spread of English might itself be a solution. As publishing in English becomes more necessary, the next generation of academics will be even better at the language.

It might prevent the kind of story where an English mathematician supposedly announced the answer to a problem at a conference, only to be told by a visiting academic that it had been solved in Russia years before.

In the future, the Russian mathematician could already have published in English.

"Certainly we can't get rid of English," says Prof Curry. The dominance of the language is here to stay and she suggests the first step in combating any problems is to begin acknowledging that they exist.