Norway seeks to diversify its economy as oil earnings plunge

- Published

Sorenga's Barcode Project was built when Norway's economy was doing well thanks to high oil prices

Looking out across the Oslo fjord, with its islands and sandy beaches, it is easy to forget that the Norwegian economy is in difficulty.

As oil prices have collapsed, it's become clear that Norway has caught what used to be called the Dutch disease - an overreliance on one industry, in this case the oil and gas sector.

With its upmarket waterfront restaurants and the Barcode office blocks, the Sorenga dockside development serves as a poignant reminder of how prosperous Norway had become while the going was still good.

"Where once there was a container port, there is now housing," says Vibecke Lyse Augdal, managing director of property rentals company Utleiemegleren, as she takes in the view from a luxury flat at this natural extension to the east of Oslo's Fjord City development.

"We're just a few yards from the central station and the opera quarter, and soon we'll have the Munch museum and the Oslo public library here too."

As the Norwegian economy bounced back following the 2008 financial crisis, the Norwegian people enjoyed enviable prosperity.

Hence, at a time when much of the rest of the world was undergoing a prolonged period of painful economic austerity, Norway had money to burn on prestigious waterfront developments such as Sorenga.

Unbalanced economy

Buoyed by its all-important oil and gas sector, Norway seemed invincible during the boom years, as Brent crude oil prices surged from less than $40 a barrel in late 2008 to a peak of more than $120 in early 2011.

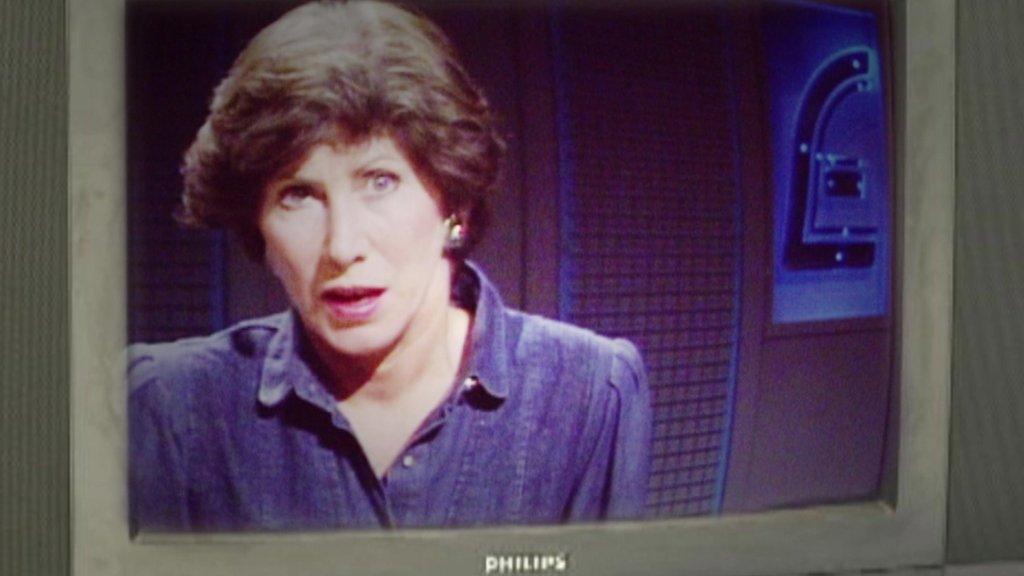

"We will not go back to the high investment level that we had three to four years ago." says Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg

In the years that followed, Brent continued to trade between $100 and $120 a barrel, and Norway was repeatedly crowned as the world's most prosperous nation by the Prosperity Index.

Then, as oil prices started to fall in 2013, it became apparent that beyond the glitz, the Norwegian economy had become incredibly unbalanced.

"The oil and gas industry became too strong in our economy, especially during the last four or five years, reflects Prime Minister Erna Solberg in an interview with the BBC News website.

"Most of the growth came from that sector, and our strong currency left some of our traditional industries behind."

Wake-up call

In the last couple of years, the price of oil has tumbled to around $30. During this period, the Norwegian energy giant Statoil, along with others in the industry, has axed thousands of jobs and scaled back contracts with suppliers.

In 2015 Statoil's earnings plunged, and it recorded a net loss of 37bn kroner, external ($4.3bn; £2.98bn).

The pain has spread. Economic growth has slowed dramatically, and this "has led to an increase in the rate of unemployment, which went above 4% of the labour force in early 2015", according to a recent OECD report.

Investment levels throughout the economy have fallen too, by about a third since oil prices collapsed.

"This will be a long-term situation", laments Mrs Solberg. "We will not go back to the high investment level that we had three to four years ago."

Well-oiled exuberance

Some regions, especially Stavanger where Statoil is based, have been hit harder than others, such as Oslo.

Norway's oil capital of Stavanger has seen jobless numbers soar as oil prices have plunged

But even here, there is a growing realisation that the prosperity enjoyed in recent years may have been temporary.

Three years ago, the Norwegian krone peaked at a 13-year high against key currencies, as the strong oil-fuelled economy provided a safe port for investors fleeing an international economic storm.

It made many Norwegians feel very wealthy indeed. Both holidays abroad and imported consumer goods seemed cheap, especially for the many dual-income households in this egalitarian nation, where salaries rose at a rate of 3-4% per year to reach an average of $33,492 in 2014, well above the OECD average of $25,492.

Both consumer spending and lending exploded during the boom years. House prices rose by about a third during the last six years.

Household debts have reached more than 200% of annual disposable income, making the Norwegians one of the most indebted people in Europe.

Much of this was fuelled by favourable tax rules for mortgages and historically low interest rates. But with most mortgages being floating rate, that could have a "significant macroeconomic" impact once interest rates start rising, the OECD has warned.

Diversification needed

The recent reversal in the Norwegian people's fortunes has already resulted in consumer sentiment weakening. House prices have all but stalled.

As yet there is little evidence of this in Oslo. House prices are holding up, as mortgage payments remain affordable thanks to historically low interest rates.

Investment levels throughout Norway have fallen by about a third since oil prices collapsed

And on the High Street, most people are still spending - even those who have lost their jobs remain solvent thanks to generous benefits, and spending by the wealthy remains strong.

"Demand remains strong, so we haven't seen an impact yet," says one of the partners in an upmarket clothing and accessories shop. "It's worse on the purchasing side, as everything's become much more expensive because of the weak krone."

Ordinary people are also responding to a fall in the mighty krone to levels not seen in four decades, by taking holidays at home rather than going abroad.

Nevertheless, it is clear that Norway can no longer rely on oil to fuel growth in its economy.

"None of us can be sure where the oil price will go," Mrs Solberg says.

"The Norwegian economy has to diversify."

Broad consensus

At last month's Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise conference in Oslo, participants were left in no doubt about the seriousness of the situation.

With a weaker energy sector, Norway is now aiming to diversify its economy

The confederation's director general, Kristin Skogen Lund, broke with tradition and invited the leader of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions, Gerd Kristiansen, to join her on stage.

"We have the highest unemployment levels since 1995, and many of those out of work are young," observed Mrs Skogen Lund.

"We agree that we must face the challenges together," Mr Kristiansen said.

The government and the central bank are also doing their bit to prevent a hard landing for the Norwegian economy.

Norges Bank reduced its key interest rate three times last year to just 0.75%, with further cuts on the horizon, and the government raided the country's seven trillion kroner ($820bn; £560bn) oil fund to pump cash into the economy.

"With growing unemployment, we need to use stimulus from the oil fund," Norway's prime minister tells the BBC, justifying the decision to fund investment and tax cuts by taking more money from the oil fund than it will put in from oil revenues, for the first time since the sovereign wealth fund's birth in 1998.

Economic stimulus

With business and labour on side, and Norges Bank committed to low interest rates, the government is orchestrating a transformation of the economy.

The hope is that Norway's weaker currency should eventually drive growth in its export sector

"Through the oil and gas sector, we have built a large services sector that can be used to support other sectors in the future," Mrs Solberg says,

She predicts growth in the aluminium industry, the healthcare sector and, not least, in fish farming and fisheries, at a time when a 4.5kg salmon, once packaged and processed, is worth more than a barrel of oil.

"In the long-term, Norway will have an economy that is more diversified, and that is greener," she says.

- Published2 February 2016

- Published21 January 2016

- Published18 December 2015