How some big firms are learning to share as well as sell

- Published

We humans do love to acquire stuff.

Cars, shoes, pizza scissors, vibrating forks and bluetooth water bottles. The list of consumer products - some pointless, some not - that we amass over our lifetimes is almost endless.

The problem is rising populations and rising aspirations mean that the earth's finite natural resources are feeling the strain.

One possible answer is simply to own fewer things. In other words, sharing, renting and swapping stuff, rather than buying it.

Access not ownership

It's a concept that has exploded in recent years.

The variety of businesses set up within the sharing economy is staggering, from cars (for example Lyft, Blablacar, RelayRides, Liftshare and Getaround) and fashion (Girlmeetsdress, Fashionhire) to meals (Grubclub, Mealsharing, Tablecrowd and Vizeats) and wi-fi (Fon).

Anything goes at sites such as Rentmyitems and Yerdle (stuff), Storenextdoor (storage), Spinlister (bikes), DogVacay (pet boarding) and Campinmygarden.

And while this model would not be possible without the advent of the internet, it's the changing attitude of the younger generation that is key to this fundamental transformation.

Comfortable with sharing photos, personal information and recommendations on social media, so-called millennials are keen to embrace this new economic paradigm, where access is more important than ownership.

"We are now in the early stages of a different model of organising economic activity," says Prof Arun Sundararajan at New York University.

Indeed he argues the sharing economy taps into a basic human need.

"We are wired for social connection. The appeal [of sharing] is to integrate some semblance of human interaction into our economic activities."

Why buy?

However, the primary driver behind the extraordinary growth of the sharing economy is somewhat more prosaic, according to expert Benita Matofska - money.

Making or saving money is what drives most people to share or rent, while the social and environmental aspects keep them coming back for more, she says.

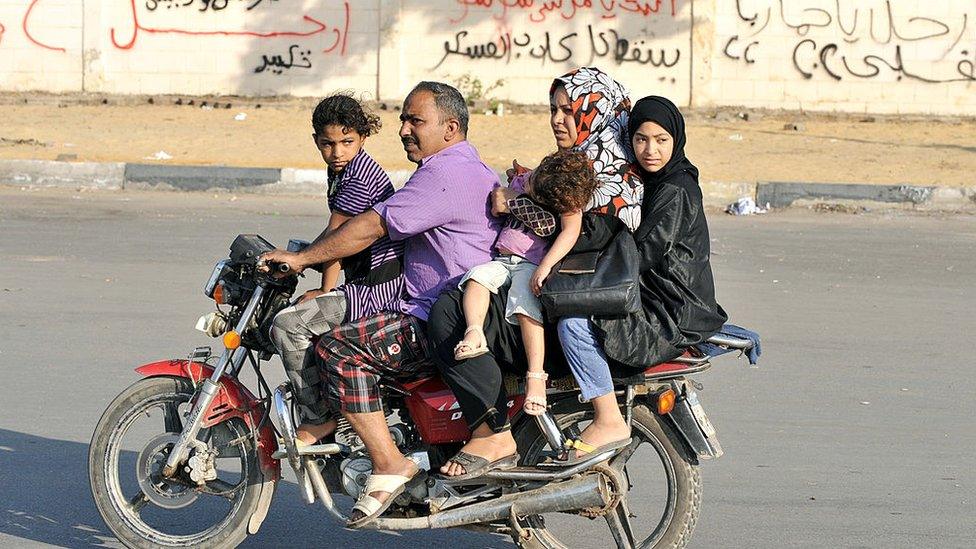

Sharing may be a way to reduce the number of cars on our roads

The benefits to the consumer are clear - you only pay for what you need, when you need it.

Why buy a car when, on average, you only use it for 4% of its life? Why buy an expensive designer dress to wear once a year when you can rent one, and rent a different one next time round, for a fraction of the cost?

Sharing is even changing the way we think about work, says Ms Matofska, with more and more people taking on one-off projects as opposed to traditional jobs thanks to shared work spaces and sites such as Upwork, Freelancer, Guru and Taskrabbit.

Airbnb is now the biggest accommodation provider in the world

But the two start-ups that stand out from the crowd are taxi service Uber, now valued at more than $60bn (£42bn), and room sharing site Airbnb, valued at $25bn.

As a recent report on the sharing economy by US Crowd Companies says, "the world's largest hospitality brand owns not a single room or hotel. The world's largest car service owns not a single vehicle".

Indeed in eight years, Airbnb now has more rooms than the Hilton Group managed in almost 100.

'Experiment aggressively'

And it's this kind of dizzying success that has grabbed the attention of the established order.

Understandably concerned that they may go the way of the music industry, where many traditional incumbents were wiped out by the advent of streaming, big global brands are desperately trying to work out how best to engage with this new economic model.

Prof Sundararajan's advice is simple: "They have to experiment aggressively with new consumption models".

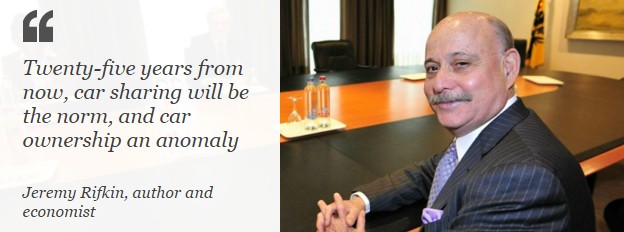

And many are. Unsurprisingly given the impact of Uber and Lyft, carmakers have also been among the first to react.

Ford is offering financial incentives to customers who rent out their cars using sharing site Getaround, while Daimler runs its own service called Car2Go.

A number of big carmakers are embracing the sharing economy

Rival BMW has also been quick to react with its DriveNow service based in a number of German cities, London, Copenhagen and Stockholm.

"There is physically not enough space for the one-car, one-owner business to grow; this is about selling one car a thousand times," explains Tony Douglas, head of mobility services at the German giant.

"Hope and threat are both drivers - it's about generating new business, [and] if we don't do it, someone else will.

"Why be a supplier for Uber or Zipcar and let them own the customer? We want to own the customer."

BMW started looking at the on-demand model four or five years ago, with a small project team of five people. It now has a dedicated and profitable business unit employing more than 100 people.

Other companies are engaging in a different, if rather less imaginative, way - by investing in or buying out sharing start-ups.

US giant General Motors recently announced a $500m partnership with Lyft, having already teamed up with RelayRides; while Hyatt Hotels has invested in Onefinestay, an upmarket room-sharing site.

Retailing, tourism, healthcare, energy supply and recruitment are likely to be the early adopters, but it's not just the private sector that is waking up to this fundamental shift in the way we buy and sell goods and services.

Local councils and charities are also looking to embrace sharing, for example Macmillan's Team Up initiative, where local people can help those suffering with cancer.

'Rebound effect'

While the advent of sharing lifestyles should in the main help relieve pressure on resources, there could, however, be some unexpected knock-on effects.

For example, cheaper and more accessible taxi services could well provide an increasingly attractive alternative to public transport, exacerbating rather than reducing emissions of CO2 and pollutants.

Indeed there is increasing talk of a "rebound effect, where people who share have more money to spend on things, which muddies the water a little," says David Symons, director of consultancy WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff.

But given that those who embrace sharing are by their very nature less obsessed with accumulating material possessions than previous generations, sharing must be seen as a force for good.