Can technology bring lawyers into the 21st Century?

- Published

The legal profession is not known for embracing technological innovation

The legal profession is perhaps more associated with bulging files of papers, odd clothing and arcane procedures than with technological innovation.

But several start-ups are trying to give this most conservative - and sometimes vexing - of professions a digital makeover.

Basha Rubin, for example, co-founded New York's Priori Legal, an online marketplace that connects lawyers with businesses, after she perceived that there were too many obstacles in the way of businesses trying to find legal services.

Lawyers listed on Priori Legal are vetted by the company and have to have five years of relevant practice experience and good references. The lawyers are also interviewed face-to-face or via Skype.

Priori Legal co-founder Basha Rubin thinks tech can help remove obstacles for businesses

"In order to stay in the network, lawyers need to maintain a 95% approval rating from Priori clients," explains Ms Rubin, but the start-up declined to reveal how many lawyers are currently on its marketplace.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong's Dragon Law is trying to bridge the gap between start-ups and legal services by helping budding companies become incorporated, draft contracts, or register trademarks online.

Dragon Law's goal is to help start-ups adopt a DIY approach to their legal issues rather than turn to traditional law firms.

Hong Kong-based Dragon Law is aiming to help start-ups become more self-sufficient

The company needing help fills in a questionnaire about its situation, then Dragon Law's software analyses the answers and comes up with the relevant forms and a plan of action.

Forewarned is forearmed

One of the reasons why legal cases can take so long - and prove so costly - is that it often takes ages to root out relevant documents and research cases.

So Docket Alarm has developed a search and alert tool to helps lawyers find and track cases. Chief executive Michael Sander, previously an attorney specialising in intellectual property, wanted to find a better way of searching for legal documents.

The Docket Alarm tool builds a profile of a case and helps lawyers guess the most likely outcomes based on a number of parameters.

Many lawyers would love to reduce the amount of paperwork they have to sift through

"You can see things like how often did people win, and how does that compare to the national average?" Mr Sander explains. "You can see if a particular judge may be more biased in one way. I'll want to switch judges if I can do that."

The better informed lawyers are, the more effective their decisions will be, Mr Sanders argues.

"Maybe I want to settle the case really quickly because I know I'm going to lose. Or if I think I'm going to win, I can request more money from the other side.

"You can use it as a tool to build a strategy for a case, rather than finding a specific case that matched up," he says.

Automating advice?

Automation and artificial intelligence (AI) promise to remove much of the grunt work involved in law. For example, Finland's TrademarkNow has come up with an AI tool for searching and managing trademarks.

But there are pitfalls with this approach in such a heavily regulated sector.

Pittsburgh's LegalSifter originally developed an algorithm that scanned contracts for freelancers and then gave advice on how to improve the terms based on comparisons with standard contracts.

But this fell foul of the regulations, explains LegalSifter's new chief executive, Kevin Miller, who joined last September: "[The company] got some nice press, but unfortunately got some feedback from more than a few attorneys who said that it was unauthorised practice of law."

So the founders and investors decided to take the company in a different direction.

With its ContractSifter program, the start-up now targets companies that need to make sense of a large amount of contracts and terms. Crucially, the new product doesn't offer advice.

John Mortimer's character Rumpole of the Bailey is the very image of the old-fashioned lawyer

It's imperative for any company to state whether or not formal legal advice is being offered, says Ray Berg, managing partner at law firm Osborne Clarke.

"So in the case of start-ups offering guidance, they need to be absolutely explicit about the nature of that advice. Founders will still need to have a trained lawyer to interpret the offerings of any software."

And wrongful interpretation of legal documents by automated programs - or humans - can have serious implications, he adds.

'Data is the oil'

Gaining access to raw data from often opaque legal systems is a huge challenge for digital start-ups wanting to expand globally, says Docket Alarm's Mr Sander.

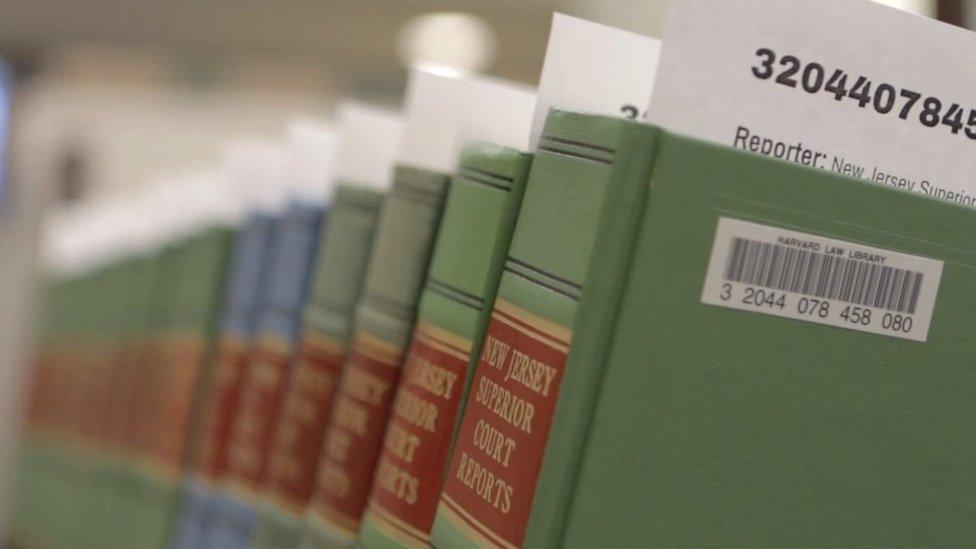

Harvard Law School is digitising 40,000 volumes of US case law for online use

Companies face hefty fees or being denied access altogether, he says.

"You actually need the data to drive these more advanced tools. In the 21st Century, data is the oil."

Harvard Law School is attempting to address this by scanning reams of court documents dating back centuries and making them available to the public.

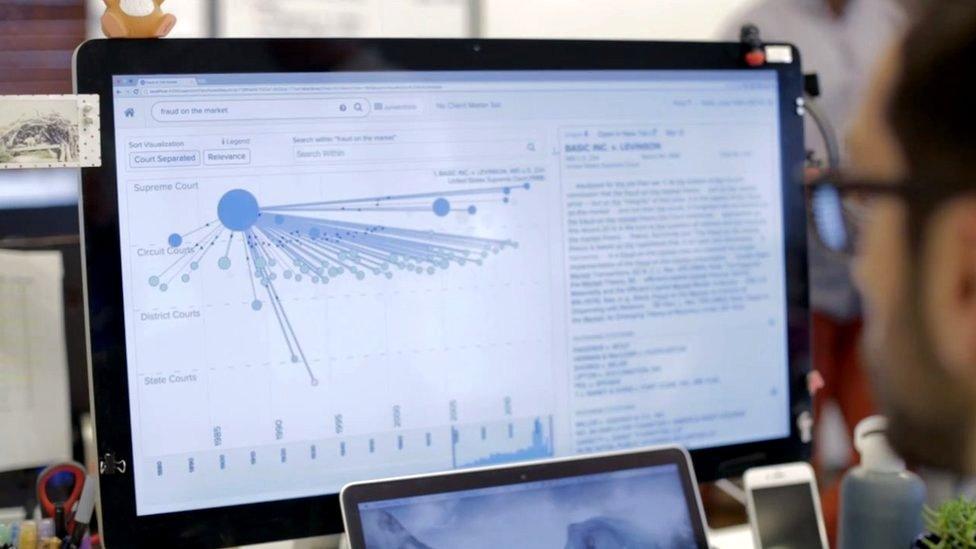

Ravel Law uses machine learning and natural language processing for easier legal searches

Californian data analytics start-up Ravel Law is assisting in the project, which will allow it to benefit from the huge database, while companies like Docket Alarm will be keeping a keen eye on the ambitious digitising process.

'Cataclysmic change'

A report from the Judiciary of England and Wales proposed the introduction of "online courts" to handle minor civil cases of up to £25,000. It would, in theory, free up the courts and be "largely automated", wrote its author Lord Justice Briggs.

But the UK's Law Society has "grave concerns" over this level of technology in the court system, which may preclude people with no access to IT facilities, who aren't IT literate, or who have learning or language impairments.

Does the legal profession want to embrace new technology or put a gavel through it?

"An online court must not be used as a way of normalising or condoning a two-tier justice system where people who cannot afford professional advice are forced to represent themselves, putting them at an unfair disadvantage," says Jonathan Smithers, president of the Law Society.

"We aren't just experts in the law; we're experts in our clients' varying sectors and markets, and so we are able to help them plan for the future," adds Mr Berg. "In this respect, a piece of software simply cannot compete."

"When we started we had a lot of sceptics but over the past three years we've just seen a tidal wave of change in how lawyers are thinking about their business and practices," says Ms Rubin.

"There's still a huge amount of regulatory uncertainty about legal tech companies across the spectrum, and that has a chilling effect, but personally I feel that we're seeing the beginning of an almost cataclysmic change."

Follow Technology of Business editor @matthew_wall, external on Twitter.