Is self-publishing coming of age in the digital world?

- Published

What has self-publishing achieved?

Erotic novel Fifty Shades of Grey began life as a humble, self-published e-book, unable to satisfy the tastes of traditional publishers.

Within a few years it had achieved domination on a global scale, spawning a series that has sold more than 125 million copies.

E. L. James's personal story has become a tantalising fantasy for aspiring authors. But one that technology and social media are making increasingly realisable.

"There was a time when self-publishing was equated with vanity," explains John Bond, co-founder of Whitefox, one of several new companies helping 'amateur' authors publish professionally on platforms like Amazon Kindle, Google Play, Apple's iBook Store or Kobo.

"Because of the digital revolution, democratisation has happened. It's almost as if the writer has become his own entrepreneur around the publication process."

Mission to Mars?

In their competition to get noticed, self-publishers are proving willing to take risks.

Andy Weir's The Martian eventually went on to become a Hollywood blockbuster. But the story was originally published chapter by chapter on the author's blog for free.

Oscar-nominated film The Martian starring Matt Damon began life as a self-published book

This turned out to be great exposure and it became a huge hit as an audiobook, e-book and physical book.

"There was an adversarial attitude between mainstream publishing houses and self publishers a few years ago," says Mr Bond, "but I think that's changed dramatically."

He attributes this to traditional publishers' new-found admiration for the self publishers' social media skills, which have helped them find new readers without the benefit of expensive marketing campaigns.

Lawyer-turned-author Mark Dawson, for example, uses his website and Facebook page, external to give out free copies of his thrillers and curates 'Readers' Groups'. Online conversations help him establish a closer relationship with his readers encouraging them to come back for subsequent publications.

Another thriller writer Joanna Penn has bolstered her following by helping others to self-publish through her website, external which explains how to go about self publishing. She also hosts a popular podcast interview series.

So-called "Instapoets" like New Zealander Lang Leav have built up huge followings on Instagram, external and Tumblr, publishing their work on these platforms, before securing traditional publishing deals.

"Not for everyone"

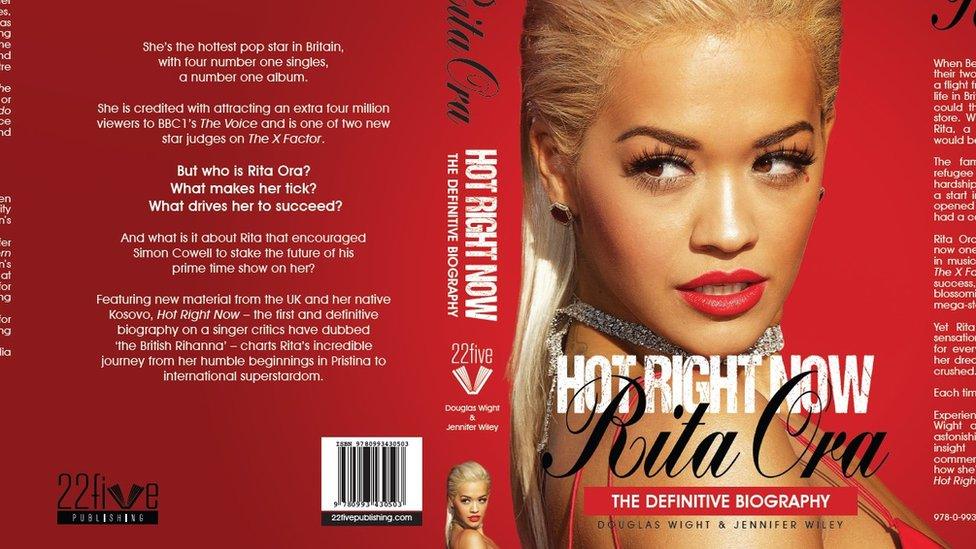

Douglas Wight has just completed his first self-published book and has a more cautionary tale to tell.

The former News of the World tabloid journalist set up his own company to self-publish a biography of pop diva Rita Ora, in the run up to Christmas.

Douglas Wight and Jennifer Wiley took control of all aspects of the publishing process

He and his co-author opted to sell the e-book version on Amazon, but also took the added risk of organising their own hardback print-run.

Self-publishing wasn't as straight-forward as he had hoped.

"You have control of what you are doing, but it's not for everyone," warns Mr Wight. "It's a lot of work and a huge learning curve."

That work includes satisfying all the different formatting requirements of the various e-book outlets, organising cover illustrations and marketing, all while bearing the financial risk of the whole enterprise, explains Mr Wight.

That said, he feels his gamble paid off.

The hardback version has sold more than 3,000 copies and performed better than expected on Kindle.

He has covered his costs and is now hoping to begin a new chapter of profitability.

After the gold rush

But what if it is not just readers you are after, but cash rewards?

Orna Ross, founder of the Alliance of Independent Authors, believes the hard work of self-publishing can pay off.

In the past traditional publishers would give the author around 10%, she says, negotiating a tough contract as they were the only route to market, with advances that were getting smaller.

New companies like Reedsy offer services like proofreading, cover illustration and marketing to support people taking the self-publishing route

Amazon may be seen in a negative light for its impact on the high street, but for self-publishers its market disruption is largely welcomed, she says.

Kindle Direct Publishing can give authors up to 70% of the purchase price. It allows authors to retain copyright and gives them a non-exclusive deal.

In the US, the most mature market, independent authors are now collectively earning more from e-books than authors handled by the so-called Big Five publishers, according to advocacy website Author Earnings, external.

However, they also charge roughly half the amount for their e-books, and there are many more of them.

Generous profit margins don't mean so much if you are selling cheap and struggling to sell at all in a crowded market.

Michael Tamblyn of Kobo originally founded BookNet Canada, specialising in digital analytics for publishing

Philip Jones, editor of The Bookseller magazine, believes it's a lot harder to make money from self-publishing now that the Kindle-inspired gold rush has petered out.

"Smart, entrepreneurial authors" could use clever marketing on social media to get their e-books into the Top Ten charts, timing it to sell enough books over Christmas to make a tidy profit.

But that trick is harder to pull off when there are so many e-books out there, he argues.

"I do worry that as the market has slowed so the number of sharks willing to take money from authors has grown," warns Mr Jones.

"Publishing, when it works properly, should be about moving money towards authors."

Into the unknown

The exact number of self-publishers and their impact on publishing is surprisingly hard to pin down.

Amazon does not disclose its e-book sales, which are worth more than a billion dollars annually in the US alone, but remain a comparatively small part of its retail empire.

Nielsen Book Research estimates that 61 million e-books were sold in the UK between January and September last year

Author Earnings, which scrapes public data from Amazon's bestseller lists for its analytics calculates that in the US, the amount of money spent on self-published books went up from around $510m in 2014 to $600m in 2015.

"E-book sales are like dark matter," says Michael Tamblyn, chief executive of e-book retailer, Kobo, though he is willing to volunteer some information.

"For us, 12% of the books we sell globally are self-published."

The fragments of available data build up a picture of a new literary landscape, where the self-published author looms large.

Follow Dougal Shaw, external and Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall, external on Twitter.