Osborne's big worry - lack of wage growth

- Published

- comments

Here's a starter for ten: What was Ed Balls' Fiscal Rule?

Any takers? No? At the back there, come on, you must have been paying attention.

Well, the then shadow chancellor announced it in 2014.

Labour, he said, would make a "binding fiscal commitment" to "balance the books, deliver a surplus on the current budget and get the national debt falling in the next Parliament".

Whether this was economically literate was not really the point - it was a political offer to the public with one central message: you can trust Labour with the public finances.

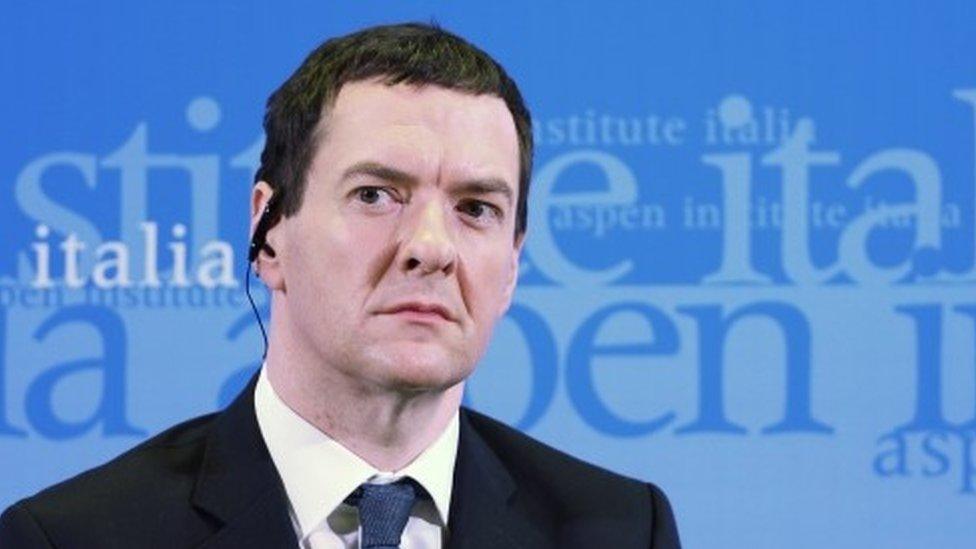

George Osborne's "fiscal mandate" is attempting something similar.

Possibilities

The chancellor has pledged to run a surplus from 2019-20 "in normal times".

Given that "in normal times" covers a whole host of possibilities - and certainly allows for a large margin of wriggle room - this again is a political rather than concrete economic offer.

Now, the Treasury seems to think such offers to the public are useful in as much as they signal the same approach to the public finances - you can trust us - as Mr Balls attempted in 2014.

But the fact that I'm not sure a lot of readers of this blog would have been able to answer my starter for ten at the beginning of this post reveals a deeper truth.

Gloomy

Mr Osborne knows that he can set as many fiscal mandates as he likes, the public are unlikely to notice.

What they are likely to notice is whether the economic growth they so regularly hear trumpeted by the chancellor is actually making a difference to their lives.

And this is where another part of the Institute for Fiscal Studies' Green Budget comes in.

Yes, the threat of further tax rises and possible public sector cuts might be very real, but the chancellor's political advisors know that one of the key motivators of voting behaviour is whether people feel, and actually are, better off.

And there the figures are pretty gloomy.

Downgrade

As I pointed out last week, one of the most important points in the Bank of England's report on the state of the UK economy was that wage growth was slowing.

Low inflation, immigration, the use of cheaper technological solutions and companies keener on repairing balance sheets than paying people more money have meant that the pre-financial crisis relationship between high employment levels and wage inflation (that one has a tendency to lead to the other, illustrated by the Phillips Curve) is stuttering.

Last year the Bank made the confident prediction that real incomes would rise by 3.75%.

That has now been downgraded to 3%.

Now, of course, with inflation at 0.2% that is still an increase.

But after the 2009-14 "great pay squeeze" which saw median incomes for all employees fall by over 9% in real terms, there is still a long way to go before economic growth releases a more confident "feel good factor" among the employed.

Offset

Yes, consumer spending is rising, as this morning's Barclays Spend Trends report reveals.

However, the fear is that the increase is being driven by increasing debt as people take advantage of ultra-low interest rates to access cheap loans.

Low wage growth is an economic problem for the chancellor.

As the IFS argues, lower wage growth means lower tax income which feeds the case that Mr Osborne may have to raise fresh taxes or find further cuts in public spending to meet his "fiscal mandate".

These will only be slightly offset by the increases mandated by the National Living Wage, as much of that increase will be paid to those below the present tax threshold.

Low wage growth is also a political problem.

Ask most people what the fiscal mandate is and you will probably receive a pretty blank stare.

Ask people if their wages are going up fast enough, and the answer will be a lot more vocal.