Companies get serious about water use

- Published

Water is unlike any other commodity on Earth.

For a start, we can't live without it, for very obvious reasons.

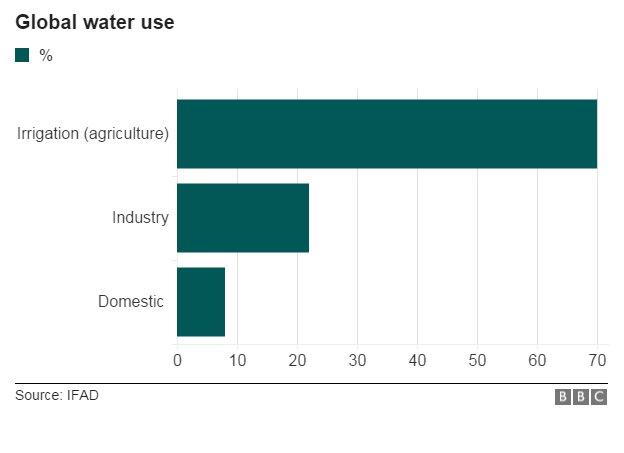

But it also underpins pretty much every activity we pursue in life - not just in our everyday lives, but in growing food, energy production and industry both large and small-scale.

Water is also unique in that it's pretty much indestructible - unlike most resources, it doesn't break down when heated up, but evaporates, constantly changing form to be transported to another place at another time.

As Betsy Otto, global director at the World Resources Institute's (WRI) Water Programme, says, "the water we drink today dropped off the nose of Tyrannosaurus rex".

This may help explain why this most precious of resources is free. For despite being incomparably more precious than any amount of gold, platinum or diamond, in most places on Earth water holds practically no financial value whatsoever.

But water can no longer be seen as an infinite resource as shortages become ever more commonplace, external across the world.

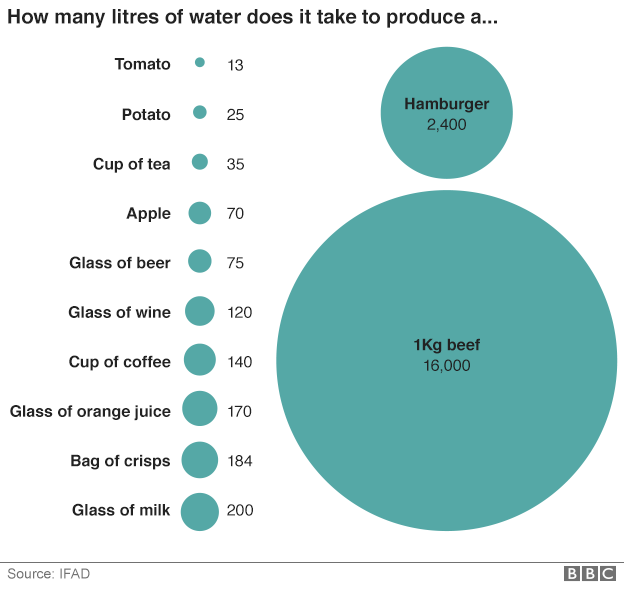

Unprecedented population growth, allied with greater wealth leading to far more water-intensive meat consumption; climate change causing more erratic weather and extreme droughts; and pollution are all putting a huge strain on finite water reserves.

So much so that more than a billion people currently live in water scarce regions, according to the WRI, a number that could grow to 3.5 billion by 2025. Indeed demand for water is projected to rise by 40% in the next 20 years.

Growing parts of the world are suffering from severe drought

To make matters worse, food and clothing production has in recent years moved increasingly to areas of water shortages - typically developing countries that have welcomed the opportunity to establish industries, creating jobs and wealth.

Indeed water and its delivery are often cheapest in the parts of the world where it is most scarce.

As Richard Mattison, head of environmental research group Trucost, says: "If jeans were made in Denmark, fine. But they're not, they're produced in parts of the world that suffer from severe water stress."

Clearly something has to give.

"We are in a race to the bottom, as if there were no supply limitations," says Ms Otto. "That needs to change. We need to understand that we are out of balance and that there are very serious risks."

'Sea change'

But the message is starting to get through.

There has been a "sea change in the last five years, led by forward looking companies", says Ms Otto, particularly in the clothing, food and drink industries.

SABMiller is just one such company. As Andre Fourie, its head of water security and environmental value, puts it, "no water, no beer!"

Acutely aware of risks to the business of water stress in the countries in which it produces - including India, Nigeria, Peru and South Africa - the UK brewer decided eight years ago to calculate its water footprint, and claims to be the first consumer goods company to do so.

It found that 90% of its water use came from growing the ingredients for its beer, such as barley and hops, rather than the actual water used to make the beer itself.

Producing beer requires a huge amount of water

More water is used growing the ingredients of beer than is used in beer itself

It resolved to cut its own water use by 20% by 2015, a target that was met "a little early". It now uses on average 3.5 litres of water to produce a litre of beer, and the company has set a target of just three litres by 2020.

But it also resolved to address the wider risks of water shortages in its supply chain, for example speaking to local mining companies and farmers outside of Lima, Peru, to reduce pollution and fertiliser run-off into local rivers.

And addressing these risks is not cheap. Such are the scale of the long and short-term risks to the overall business, the company is prepared to spend serious amounts of money to secure not just its supply of water, but its quality as well.

SAB typically spends $500,000 in each locality it operates, which may be home to just one brewery.

US clothing giant Levi Strauss, best know for its jeans, is another leader in water conservation.

Five years ago, understanding that water was a "critical" issue for its business, the company initiated a drive to reduce water use in its supply chain without compromising quality.

It is now using 96% less water in making a pair of jeans - far less than the industry average of 11,000 litres.

Levi's has gone to great lengths to reduce water use in its various factories

Making jeans is an incredibly water-intensive process

Actions like these will "reduce operational and reputational risk, [help] manage costs and generate growth through product innovation", says Michael Kobori, vice president of sustainability.

This initiative has saved not only one billion litres of water, but also energy consumption, and it has translated into a costs saving of 4 cents (2.8p) per pair of jeans.

Elsewhere, the consumer goods giant Unilever and the carmaker Volkswagen have spent several hundred thousand dollars on planting trees to secure their water supplies in Africa and South America.

The coffee giant Starbucks has committed millions of dollars to protect the water supply to its coffee plantations in Mexico and Indonesia.

Microsoft is even experimenting at vast expense with putting data centres under the ocean off the coast of California in a bid to reduce the water needed for cooling.

Human right

There are numerous, very real threats to water supplies for corporations the world over, primarily in agriculture, energy, utilities, IT and mining, but also in food and drink, clothing, consumer goods, retailing and beyond.

The great unknown is whether, one day, water itself rather than the delivery of it will be priced to reflect its uniquely important role in the global economy and to the human race.

Some argue that as a basic human right a price can never be put on accessing water; others that it is an unavoidable necessity.

A precedent has already been set in California and in the Murray Darling Basin in Australia, where water trading systems have been used successfully to reduce water use dramatically in times of drought.

If such schemes became widespread, the consequences for the corporate world would be dramatic.

Indeed research by Trucost suggests that more than half of the profits of the world's biggest companies would be at risk if water was priced to reflect its value.

Companies need to act now before it's too late.