Why is Britain's Barclays Bank pulling out of Africa?

- Published

If Barclays is selling its African business, what does that tell us about the bank's view of the continent?

As the UK bank Barclays announced its full year results, local markets were less interested in the numbers and more interested in the back story.

The rumour mill had already been churning for months that there would be a big shake-up.

More specifically there were murmurs, now of course confirmed, of a sale in Africa.

And all this talk of Barclays wanting to get rid of its 62% stake in its Africa business is naturally viewed as an indication that the story of African growth isn't as real as many "Africa rising" headlines have been suggesting.

When a leading British bank gives up a legacy and a long history of operating in Africa, it's not a good a sign.

Bogged down

However the story of Barclays' supposed failure in Africa has as much to do with Barclays as it does with Africa as a continent.

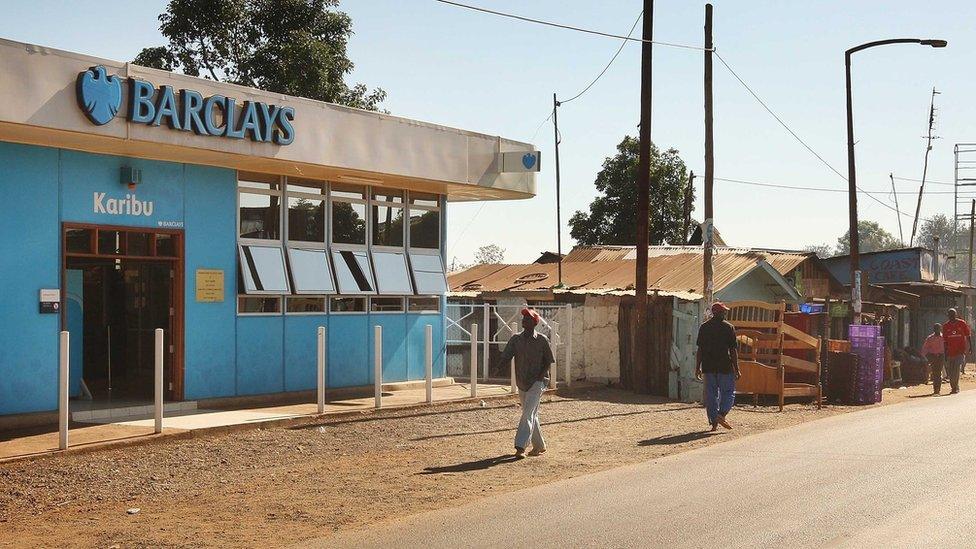

Even though Barclays has maintained a presence in Africa for more than a century, the bank was very slow in taking up the fresh opportunities that presented themselves in the past decade.

Barclays was not as nimble as other banks, such as Standard Bank, Ecobank or GT Bank, which have been snapping up opportunities in Africa.

It was bogged down by the internal bureaucracy of tying up all its assets in a merger with South Africa's ABSA bank in order to create Barclays Africa.

That process began in 2005, and is yet to be fully completed, and both banks have retained their separate identities thus far.

Barclays in Africa

Barclays has had a presence in Africa since 1925

Barclays Bank Plc currently owns 62.3% of Barclays Africa Group Limited (BAGL) which controls banks in 10 African countries including Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda

Barclays Africa Group employs 45,000 people across the continent

Barclays Bank Plc has announced plans to dramatically reduce its stake in BAGL

In addition Barclays owns Barclays Bank Egypt and Barclays Bank Zimbabwe which it also plans to sell

A full rebranding exercise was suspended a month ago, which should have been an indication of things to come.

The process took longer than had been anticipated which required global shareholders to wait patiently before earning the fair value for their stake.

Continental problems

But the challenge for Barclays has certainly been compounded by the volatility in global markets over the past year, the downturn in the commodities cycle, the slowing of China and the depreciation of many African currencies.

So the opportunities for more growth in Africa simply dwindled.

That may have created fears within Barclays that local African economies simply weren't ripe for retail banking.

In other words the thinking might have been that in the near future the signs were not promising.

The unemployment figures suggested that not enough jobs were being created for young Africans to start opening up personal and business banks accounts.

Many African economies have grown strongly over the last decade, including Nigeria: but Barclays isn't convinced the future is rosy enough

That doesn't bode well for a bank looking to increase its footprint on the continent.

It's quite unfortunate that Barclays was seemingly ham-strung in a situation where it should have had first mover advantage, having been in Africa for almost a century.

Staley's moves

Another important variable is Jes Staley himself. The new chief executive was appointed in late October and in less than six months he has made bold moves.

The urgency with which he is acting creates the impression that he's under pressure to turn things around - quickly.

From the moment he took over, he immediately raised concerns about the volatile market conditions that have seen the economies of Asia and Africa slowdown.

Chief executive Jes Staley says Barclays owns 62% of the assets but shoulders 100% of the liabilities for its African business, the reason he cites for wanting change

It's important to note that Mr Staley is not only pulling out of Africa, but also plans to downsize in other emerging markets such as in Asia, Russia and Brazil.

As the situation worsened and African currencies became weaker, the argument to stay on the continent became less compelling.

Of particular concern, has been the current state of the South African economy since Barclays Africa is listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

An almost 40% fall in the value of the South African Rand since the beginning of 2015 inadvertently reduced the value of shareholders equity into Barclays Africa.

Unfortunately there is not much that banking executives can do to resolve global volatility and general perceptions about the state of the South African economy.

So without guarantees of when the situation would improve Mr Staley has opted to leave.

Who will buy?

The focus now is going to be on the steps that need to be taken in order to sell Barclays' stake of an almost two-thirds majority.

It doesn't come cheap.

Potential investors would need to raise nearly $4bn to buy Barclays.

In these markets, that could be deemed quite expensive.

Since January 2015, the South African currency has depreciated by almost 40%

In itself the sale will inspire a new round of speculation and possibly more rumours.

Already, there is talk of that the Public Investment Corporation, South Africa's largest pension fund, is interested.

But more investors will have to come to the party in order to foot that bill.

Depositors may be worried about what will happen to their funds.

Both Barclays and ABSA have assured bank regulators that depositors' funds are safe, and only share certificates will be changing hands.

Lost shine

Experts do not foresee a run on the banks.

However for African countries needing a cheerleader, the Barclays sale will have the opposite effect.

It signifies high risks in Africa, low growth prospects and lost shine.

The repercussions will be felt in the long term, as other investors decide take the Barclays cue and sell-up to refocus on Europe and America, the markets now deemed safer and better.

- Published1 March 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published1 March 2016