China opens a new university every week

- Published

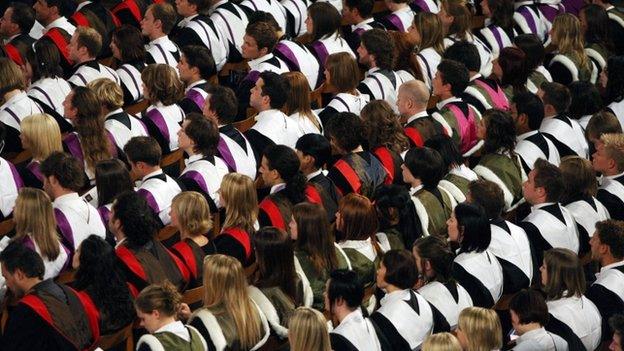

China has outstripped the US and Europe in graduate numbers and the gap is growing wider

China has been building the equivalent of almost one university per week.

It is part of a silent revolution that is causing a huge shift in the composition of the world's population of graduates.

For decades, the United States had the highest proportion of people going to university. They dominated the graduate market.

Reflecting this former supremacy, among 55 to 64 year olds almost a third of all graduates in the world's major economies are US citizens.

But that is changing rapidly among younger generations. In terms of producing graduates, China has overtaken the United States and the combined university systems of European Union countries.

China is moving from cheap production to an economy of high skills

The gap is going to become even wider. Even modest predictions see the number of 25 to 34-year-old graduates in China rising by a further 300% by 2030, compared with an increase of around 30% expected in Europe and the United States.

In the United States, students have been struggling to afford university costs. In Europe, most countries have put a brake on expanding their universities by either not making public investments or not allowing universities to raise money themselves.

But if the West has been sleeping, China and other Asian countries such as India have raced ahead.

It isn't simply about bigger student numbers. Students in China and India are much more likely to study mathematics, sciences, computing and engineering - the subjects most relevant to innovation and technological advance.

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

In 2013, 40% of Chinese graduates completed their studies in a Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subject - more than twice the share of US graduates.

So the graduates who are the cornerstone of economic prosperity in knowledge-based economies are increasingly disproportionately likely to come from China and India.

Graduate numbers in the US and Europe have been overtaken by China and India

By 2030, China and India could account for more than 60% of the Stem graduates in major economies, compared with only 8% in Europe and 4% in the United States.

Countries like China and India are betting on the future with this.

With such an increase in people in higher education, conventional wisdom might assume that the value of qualifications would suffer from "inflation".

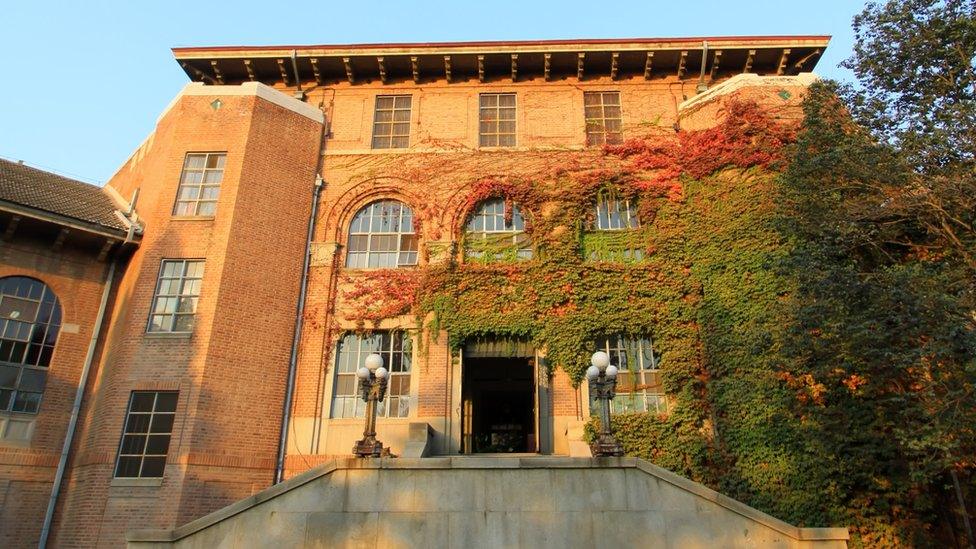

Tsinghua University, founded over a century ago, now has many newly-opened competitors

But this is not happening. In the OECD countries with the biggest increases in graduate numbers, most continue to see rising earnings.

This suggests that an increase in "knowledge workers" does not lead to a decline in their pay, unlike the way that technological advancement and globalisation have pushed down the earnings of poorly-educated workers.

In the past, OECD countries competed mostly with countries that offered low-skilled work at low wages.

Today, countries like China and India are starting to deliver high skills at moderate cost.

Students queue to take a college entrance exam in Wuhan

The West cannot compete by keeping the rest of the world out of their economic systems. There are plenty of examples of European countries that have stagnated over the past century by trying to do just that.

The massive investment in education in Asia suggests competition through lower production costs may be merely a transitional strategy for countries on their way to meeting the Western world at the top of the product range.

The real challenge for Western countries is to prepare for future competition with Asian economies in the knowledge sector.

Some raise doubts about the quality and relevance of the degrees earned in China.

China has seen a rapid change in its economic identity

Indeed, there are still no direct measures that allow for a comparison of the learning outcomes of graduates across countries and universities.

But China has shown the world that it is possible to simultaneously raise quantity and quality in schools.

In the latest round of the OECD Pisa tests, the 10% most disadvantaged 15-year-olds in Shanghai scored higher in mathematics than the 10% most privileged 15-year-olds in the United States.

Perhaps tellingly, objections to the OECD's proposal for international comparisons between institutions of higher education did not come from Asia, but from countries like the United Kingdom and the United States.

Did they fear that their universities might not live up to their past reputations?

China's rapid expansion in higher education shows the scale of the challenge for the West and shows the future might be indifferent to tradition and past reputations. It might be unforgiving of frailty and largely ignorant of assumptions about custom or practice.

Success will go to those individuals, universities and countries that are swift to adapt, slow to complain and open to change. The task for governments will be to ensure that their countries rise to these challenges.