EU referendum: 1975 and 2016, a tale of two campaigns

- Published

Back in 1975 businesses were solidly behind the Yes campaign

It wasn't called Brexit then, but 41 years ago British businesses had few doubts about Europe. They campaigned enthusiastically to take Britain into the European Economic Community (EEC) or Common Market in 1973.

Two years later the business sector again rallied to the cause in the 1975 referendum, pressing managers, workers and consumers to vote to stay in.

But in the four decades since, businesses, managers and employees - and the UK itself have all changed.

Yet 1975 and 2016 do have some striking parallels.

The Labour leader Harold Wilson had promised in his election manifesto to renegotiate the country's terms of EEC membership and then put it to a referendum.

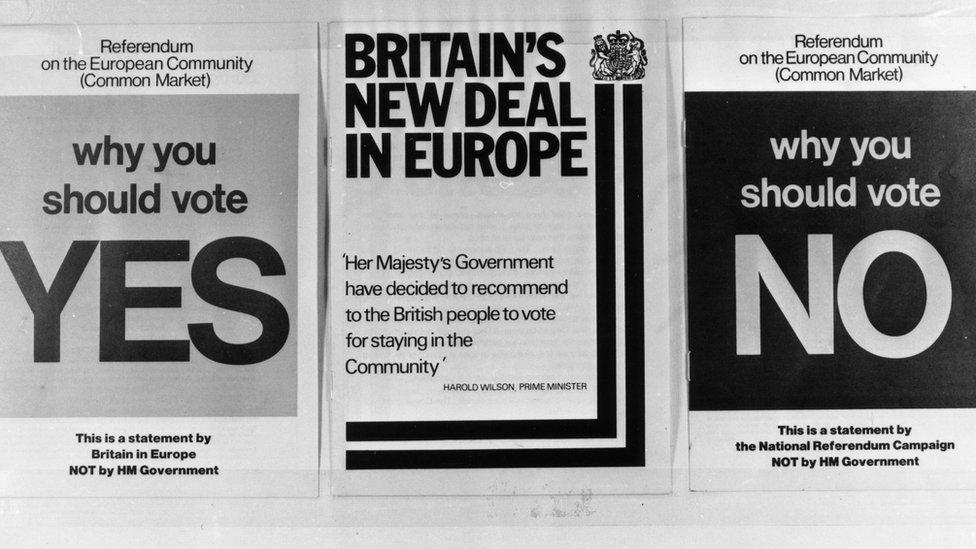

What were the key arguments when the UK voted on Europe back in 1975?

He won the October 1974 election, renegotiated with Brussels, put the deal before Parliament and then held the vote on 2 June, 1975, with a deeply divided cabinet.

Barbara Castle, then health secretary, summed up her disdain for the way the previous Conservative government had signed up the UK to the Common Market: "They lured us into the Market with the mirage of the market miracle."

Businesses thought very differently. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) polled its 12,000 members and discovered only eight wanted to leave.

It then swung behind the "Britain in Europe" campaign, creating what proved to be an unstoppable momentum.

Barbara Castle: "They lured us into the Market with the mirage of the market miracle"

Momentum

"Commercial giants like IBM, ICI, Ford, Rolls Royce, Barclays, Rio Tinto, Imperial Tobacco, WH Smith and British Steel campaigned vigorously for British membership," says historian Robert Saunders of London's Queen Mary University, and author of a forthcoming book on the 1975 referendum.

They canvassed "not just their workforce but their shareholders, customers, employees' families and those on company pensions," he says.

"They were joined on the front line by consumer organisations, trade associations and the National Union of Farmers.

"This was a levee-en-masse by Britain's commercial sector, of a kind never before seen at a British election."

The financial power of big business was formidable. Sainsbury's and BP's donation alone were three times that of the entire "No" campaign.

In 1975, the financial donation from just two firms was three times that of the entire No campaign

But more important was the leverage business had on its workforce. CBI members nominated a "Mr Europe" in each firm who received regular posters and leaflets.

Firms could commission letters and articles, to be inserted in company magazines, or hire TV cassettes for display in the workplace.

Treading warily

In 2016 the business sector is treading more warily.

When 36 leaders of FTSE 100 companies wrote to the Times newspaper in support of the EU membership, it was perhaps more notable that the 64 other FTSE 100 leaders had stayed silent.

The money is not flowing quite so consistently into the Remain camp now as it did into Britain in Europe then.

To take one example, in 1975 the clearing banks contributed £200,000 (about £1.9m today), external.

Business has learned lessons, not just from 1975 but also from Scotland's referendum

This year, it's certainly true that banks are broadly supporting the Remain camp: Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America and others have all donated to the Britain Stronger in Europe Campaign.

However, some have broken ranks - most notably among the hedge fund community: Sir Michael Hintze, founder of hedge fund CQS, and Crispin Odey of Odey Asset Management both support the EU Out campaign.

Yet by far the biggest change has been in the business landscape that in 1975 was dominated by big companies with large unionised workforces.

The rise of the SME

Since the 1980s entrepreneurs and small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs) have become a force to be reckoned with.

Back in 1971 the Bolton Report, external declared that small businesses were in long term decline, and estimated they employed 4.4 million workers or 18% of the national workforce.

It was famously wrong.

The statistics from 1971 are not perfectly comparable with today but there is an unmistakeable trend. By 2014 SMEs accounted for 12.1 million workers, external or 40% of the workforce.

And that makes a big difference to the referendum.

Four decades on, the CBI is officially refusing to align itself with either side

"Small businesses are much less supportive of the EU," says Prof John Curtice of Strathclyde University.

"Because generally they do not enjoy the export advantages of the EU but still have to comply with all the rules and regulations.

"There is also an educational aspect to all this. There is a strong link between educational attainment and the Remain side.

"Big businesses tend to employ graduates while entrepreneurs are less likely to be graduates, so small businesses tend to be less supportive."

Officially the CBI's position is markedly different from the one it took in 1975. Director general, Carolyn Fairbairn, said, external: "it's not our role to tell people how to vote ... our role at the CBI is to help inform this crucial choice. "

However, she added: "A resounding 80% of CBI members think that remaining in the EU would be best for their business."

The research it is producing generally supports the Remain camp. Its latest report states, external that a UK exit would cause a "serious economic shock", potentially costing the country £100bn and nearly one million jobs.

The British Chambers of Commerce with its broader membership, including SMEs, is taking a similarly impartial line, to the point where its director general, John Longworth resigned after being suspended for saying the UK's long-term prospects could be "brighter" outside the EU.

Lessons learned

Business has learned lessons, not just from 1975 but also from the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, when many business people came away bruised by their reception at the hands of independence campaigners.

"Any kind of intervention by business was monstered on social media as illegitimate and undemocratic, an attempt to intimidate voters by the 'London establishment'," says Robert Saunders.

But he argues that business is on a firmer footing in this vote.

"There's a stronger sense of the right of business to speak on the EU debate, given how much it revolves around trade.

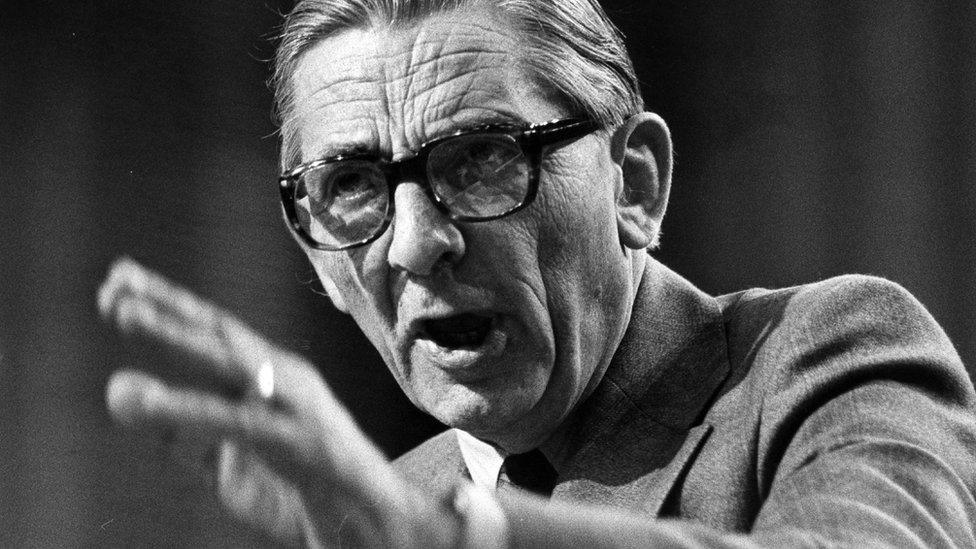

The TUC's Len Murray campaigned vigorously against EEC membership in 1975

"The CBI has some very smart people working on the campaign and I think they've learned from the Scottish experience.

"They'll want to avoid the perception that it is only big multinationals that want to stay in, by talking as much as possible about small-to-medium sized businesses."

"Rich man's club"

That perception worried the CBI back in 1975, too.

"Mobilising the business sector risked antagonising the trade unions, while giving purchase to left-wing claims that Europe was a 'rich man's club'," says Robert Saunders.

"Nothing was more likely to energise the union movement than a campaign to enrich their bosses."

Britain has changed a lot in the past four decades - yet its relationship with the EU remains a contentious issue

The answer was to concentrate on jobs, an issue where management and workers could stand shoulder to shoulder.

So when the carmaker British Leyland warned that it would have to shrink by 25% if the country voted "No" it was hard for unions to argue back.

But argue they did, and the TUC under its director general Len Murray campaigned vigorously to leave the EEC. They lost, against a landslide vote to stay in.

Today the TUC supports EU membership saying it protects workers' rights and jobs.

But several unions such as Aslef and RMT are campaigning for Brexit, claiming the EU is a "rich-man's club" or "pro-austerity, anti-worker".

If anything can be said of the last 41 years, it is that the old social and class-based divisions may have gone - but the ranks of the unions and businesses have become truly fragmented.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published5 March 2016

- Published15 March 2016