Bringing central Johannesburg back to life

- Published

Propertuity paid for a giant mural of Nelson Mandela

It is fair to say that Johannesburg still has a fearsome reputation.

The largest city in South Africa, it has endured appallingly high crime rates for decades.

This has been particularly the case for Johannesburg's inner city area, which from the 1990s onwards was abandoned by companies and middle class residents who fled to the northern suburbs and the increased security of gated communities.

Back in the early 2000s, in one part of the inner city called Maboneng photographers from the Star newspaper were able to capture images of car-jackings by simply learning out of their office windows.

Full of empty, derelict warehouses that had been built in the first three decades of the 20th Century, Maboneng was a forbidding and dilapidated place.

You would not have wanted to go there in daytime, and under no circumstances at night.

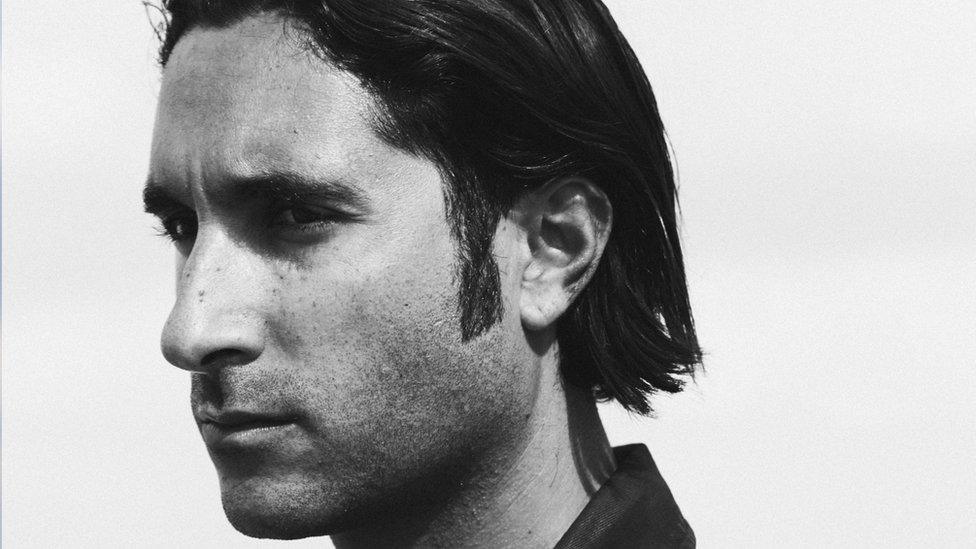

Jonathan Liebmann was raised in Durban and Johannesburg

Yet since 2008, Maboneng - which means "Place of Light" in Sotho, one of South Africa's 11 official languages - has been staging a remarkable rebirth.

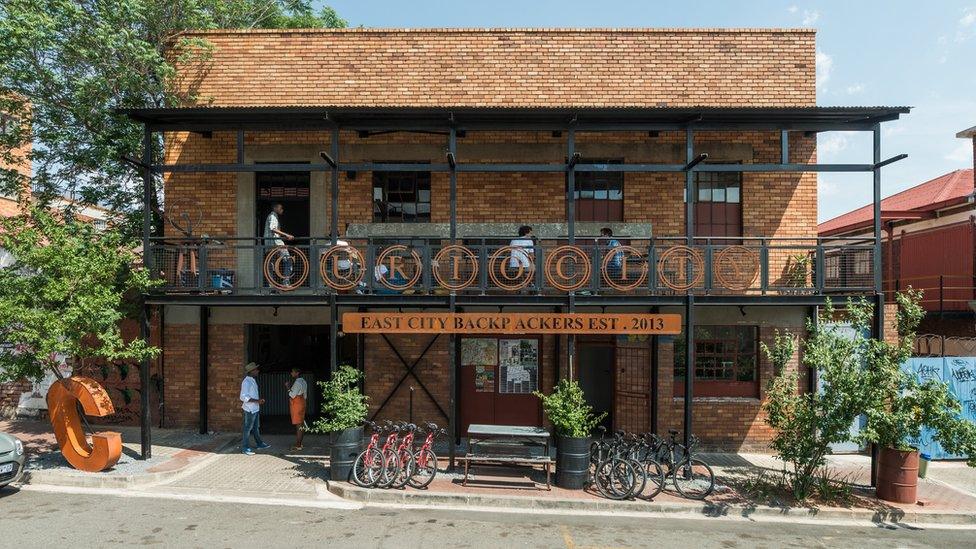

The area has being transformed into a fashionable destination, with the warehouses being turned into hotels, shops, cinemas, art galleries, bars, a youth hostel and apartments. And crime rates have fallen sharply.

Helping to lead the redevelopment is 33-year-old South African entrepreneur Jonathan Liebmann, who is the founder and chief executive of property development company Propertuity at the forefront of Maboneng's metamorphosis.

The redevelopment of Maboneng has created a lively arts scene

Mr Liebmann bought his first property in Johannesburg when he was 19, a flat which he renovated and then sold for a profit, and has never looked back.

In 2007, aged just 24, he set up Propertuity, and a year later the firm bought its first building in Maboneng. It has now developed close to 40 sites in the area.

"We specialise in taking a holistic, neighbourhood approach," he says.

'Very inspired'

Growing up in Durban and Johannesburg, Mr Liebmann studied business and accounting at Monash University in Johannesburg.

He had already shown his entrepreneurship mettle at school, where he organised discos, but it was travelling the world in his gap year between school and university which he says provided the inspiration for his future property firm.

Maboneng had a reputation as a part of town to avoid

Travelling around Europe, Asia and the Middle East, he says he was fascinated by how conurbations outside of South Africa made much better use of their city centres - particularly the fact that people actually lived in them.

"I got very inspired about cities, and the way that people use cities optimally, as opposed to the way people use cities in South Africa, which is basically that people don't really use cities properly," says Mr Liebmann.

"When I see that things are done properly, be it Tokyo, New York, Sydney - best practice examples - I appropriate and customise them, so they are locally relevant [to Johannesburg]."

Mr Liebmann has been at the forefront of redeveloping inner city Johannesburg

Returning to South Africa after his travels, Mr Liebmann's first business venture was a number of mobile coffee shops, thanks to money from family and friends.

He then set up a chain of 17 launderettes, but keen to focus on property development, he sold this business to use the funds to launch Propertuity.

"At one point I was running lots of businesses, and had property happening on the side. Eventually it became my main business."

Subsequently growing the business with the help of bank loans, Propertuity now employs 85 people and has a property portfolio worth more than 1bn South African rand ($65m; £45m).

'Mixed income'

A key component of Propertuity's redevelopment work has been commissioning - and paying for - giant artwork in Maboneng, such as a 10-story painting of Nelson Mandela, which helps to make the area more visually appealing.

"Up front there was a very strong focus on art," says Mr Liebmann. "And we continue to invest in the arts."

The company's schemes use a mixed-use model, combining apartments with businesses

He also says that Propertuity takes a "massive role" in the design of each of its schemes.

"It is not like we just hire an architect, give them the keys and say 'get it done'. It is very much a dialogue between myself and the architects."

While some critics say Mr Liebmann is gentrifying Maboneng and making it unaffordable for people on low incomes, he argues this is not the case.

Hostels and hotels have now sprung up in Maboneng

"We pride ourselves on being both mixed income and mixed use," he says.

"On the mixed income [issue], it just lets those disparities of income, which are so rife in South African society, start being bridged."

Tony de Munnik, a leading member of City Improvement Districts, a voluntary organisation that tries to co-ordinate better redevelopment within Johannesburg, says the city could do with more people like Mr Liebmann.

"Every now and then something happens and someone stands up in what otherwise appears to be a hopeless scenario," he says.

"Maboneng is that something and Jonathan Liebmann is that someone."

Mr Liebmann himself lives and works in Maboneng, and walks a few minutes each day from his flat to Propertuity's main office.

With more funding now secured for the business, he now plans to replicate what he has achieved in Maboneng in Durban.