Why do so many brand spin-offs fail?

- Published

Jewellery and watchmaker Bulgari has moved into hotels

If the name Giorgio Armani came up in a game of word association, what would you say?

It's a fair bet that clothing or jewellery popped into your head, but how about posh apartments? In fact, the Italian fashion designer is now creating swanky homes around the globe from China to India and the UK.

Similarly surprising examples abound from car firm Bugatti opening clothing stores to fashion designer Vivienne Westwood opening a restaurant in Hong Kong.

And there are countless examples of luxury firms which have lent their name to anything from baby bottles to furniture.

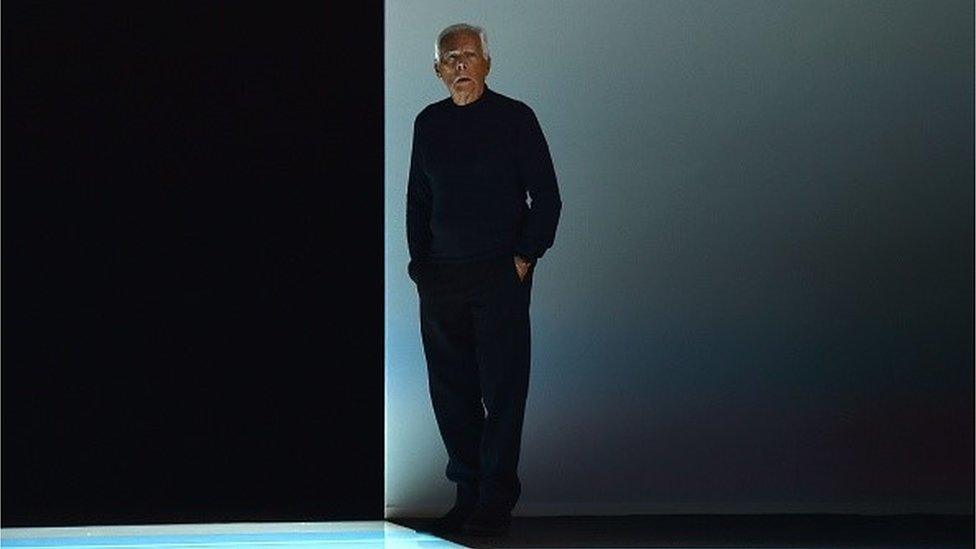

Italian designer Giorgio Armani has moved from fashion into high end apartments

It's a natural move for a company which is successful in one area to try to extend its reach into new ones, and the attractions are obvious.

'Cautionary tale'

It can seem "irresistibly profitable, for doing practically nothing," says management consultant and author Peter York, who has been an adviser to many large luxury businesses.

Yet if it isn't done well, branching out from their core business risks harming a luxury firm's reputation.

Pierre Cardin is known for his geometric shapes and space age clothing designs

Mr York cites fashion firm Pierre Cardin as "a cautionary tale".

The Italian-born France-based designer was one of the pioneers of brand licensing and his name is now carried on hundreds of products, from shirts and bottled water to tins of sardines.

'Why not?'

While the approach made Mr Cardin - dubbed "the licensing king" - wealthy, with him estimating his private empire was worth €1bn ($1.5bn; £897m) in 2011, some say it has meant the brand is worth less as a result.

Mr Cardin himself however was unapologetic, telling The New York Times, external: "I've done it all. If someone asked me to do toilet paper, I'd do it. Why not?"

But Mr York says Pierre Cardin is a classic example of stretching a brand too far. "In the end, if you overdo it, your brand is devalued. I think the brands which are most careful have the longest future."

Yet determining when a brand has gone too far is not necessarily clear cut.

Elizabeth Taylor was reported to know just one word in Italian: Bulgari

A Harvard Business Review study of 150 luxury brand extensions says that the number of new areas a company extends into isn't a problem by itself, but says their success depends on whether they are "adjacent" products: things which have some kind of logical link to the company's main offering.

It's an approach which Italian jewellery and luxury goods firm Bulgari has tried to take.

The firm, which was founded over 130 years ago by a silversmith and started off making jewellery and accessories, became familiar to a wider audience in the fifties and sixties as Rome's large film studio Cinecitta took off.

Roman Holiday, Ben Hur, War and Peace and La Dolce Vita were all shot in the famous studios, and a parade of film stars and producers discovered the Italian brand whilst there, helping to win the brand global recognition.

Elizabeth Taylor, it was reported, knew just one word in Italian: Bulgari.

Bulgari is now planning to open three more hotels

Bulgari chief executive Jean-Christophe Babin said it was this international reputation that drove it to expand beyond Europe, opening its first flagship store in New York in the 1970s.

Gradually it also moved beyond jewellery into watches, fragrances and eventually bags - all of which Mr Babin said fitted in with the firm's "mission of making the lady more unique, more special".

Yet, more recently, it has made what seems like a rather surprising leap, venturing into the hotel business.

It opened its first hotel in Milan in 2004, and in the 12 years since has opened just two more, although a further three are planned.

Knowing when to say 'no' is the secret to succeeding, says Bulgari boss Jean-Christophe Babin

Mr Babin says a hotel stay is the "ultimate luxury experience" and suggests that it's similar to the way that its jewellery, often bought to mark a marriage or a birthday, becomes part of an experience.

"The hotel is not something that stays with you forever, but it can create a unique emotion and memory you will keep with you forever," he says.

He believes that if Bulgari's foray into the sector has succeeded it is in part because they've kept the hotels small "as if they were a private house", and limited their number, enabling them to retain tight control over their quality.

"When you move from a core business to a new business, the temptation is often to take it less seriously. We've approached the new businesses in a very authentic way and are treating them as top priorities," he says.

Take your time, is Bulgari's advice on extending your brand

The fact hotels are not the firm's core business has also removed the pressure for a quick return on their investment, he says.

But the real trick, he says is to say no. "For the three [hotels] we're going to open, we've reviewed 50 to 100 projects and we have said no in 97% of cases."

For Silvio Ursini, creative director of the hotels and resorts division, it's even simpler.

"Don't venture into a business just because it's there or you want to grow. Do something only if you have something to say," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by Life of Luxury series producer Neil Koenig.