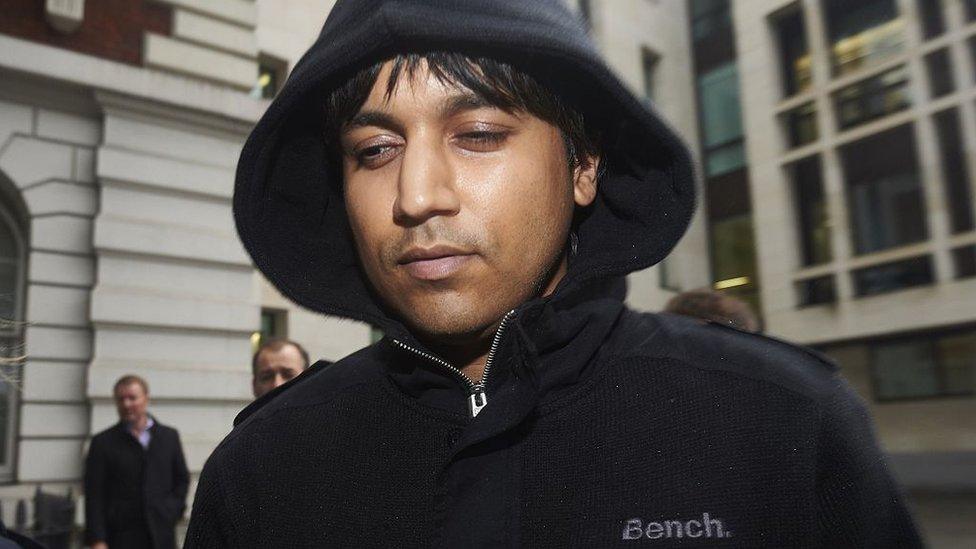

Navinder Sarao: The man accused of causing the US market to crash

- Published

Navinder Sarao, the so-called "flash crash" day trader has been fighting attempts to extradite him to the US

Navinder Sarao, who traded from his parents' home in Hounslow, west London, has been accused of market manipulation that caused a 1,000-point fall on the US Dow Jones index in 2010.

He faces 22 charges in the US, including fraud charges, all of which he denies - which include "spoofing" - the practice of buying or selling with the intent to cancel the transaction before execution.

Set aside for a moment Navinder Sarao's guilt or innocence. What he did was astonishing.

From a computer in the bedroom he'd grown up in, at his parents' semi-detached house under the Heathrow flight path, this casually dressed 37-year old traded remotely on an exchange in Chicago he had never visited.

In less than five years he made more than £30m.

Computerised trading

Pause for thought. He was operating on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a highly computerised market where normal human beings stand little chance.

Computers operating so-called high frequency trading programmes pick up any sign of prices moving up or down - and jump in ahead of normal, slow-motion human traders.

Computers will always beat humans when it comes to trading

You, the human trader, may see an order to buy pop up on your screen half a second after it's published on the exchange. It may be big enough to move the market up - so you could make money if you could buy quickly.

But because you're up against computers, by the time you click 'buy' it's already too late. Your brain took half a second to process the visual information - whereas a computer picked it up in a few milliseconds.

The high frequency traders bought, the price rose - and you lost your chance to make money.

In Chicago, the pressure is fierce to see buy and sell orders just a few milliseconds ahead of the other guy.

Millisecond advantage

As outlined in Michael Lewis's brilliant expose Flash Boys, a few milliseconds' head-start is worth so much money that the most determined traders buy expensive property close to the exchange and spend large sums installing super-fast cables - so the signal arrives just a few milliseconds faster.

Why? Because if your computerised trader gets the information two or three milliseconds before others, you can make money.

But computerised trading does have a weakness, especially if the computers are programmed to react in similar ways

If it's a big buy order your computerised trader can buy ahead of others, "riding the trend" and adding to upward pressure on prices.

The others who get the information a flash later can't "get in at the ground floor". Instead they buy after prices have already risen. And they're buying at those inflated prices from you - as you sell out for a quick buck.

'Spoofing' the computers

What Navinder Sarao seems to have worked out, like others before him, was that the high frequency trading made the market twitchy.

Because many of the high frequency traders were programmed with similar software - designed, for example, to spot a large volume of buy orders and then ride the trend - they would all do more or less the same thing.

Like a pack of sheep sent one way or another by a sheepdog, they could be spooked.

Or rather, "spoofed". According to the FBI's investigators, Nav Sarao had modified a commercially available piece of software - a trading algorithm, to do just that.

The FBI didn't only accuse Mr Sarao of placing fake orders to manipulate the market, it also accused him of helping to cause the flash crash

Using that software and at high speed, they alleged, he was placing big sell orders, sometimes amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars a day - trades with which he never intended to go through.

Instead they were designed to make the rest of the market (the computerised traders) believe the sell orders outweighed the buy orders, indicating the market was about to head down.

Sheep-like, the computerised traders would sell in order to avoid losing too much money as prices dropped. The weight of selling would push prices down.

Meanwhile (according to the FBI) Mr Sarao would have placed a real buy order waiting for the market to drop. He would then buy at the lower price and cancel the sell orders.

When the market realised the sell orders had gone away, prices would bounce back. And Mr Sarao could then sell at that higher price and bank a profit.

That profit might be tiny. But if this operation were repeated hundreds of times per hour, the profits could be handsome.

Crucially, according to the FBI, those orders were fake, designed to "spoof" the market. Sarao didn't intend to go through with them. And that spoofing is an offence under US law.

The FBI didn't only accuse Sarao of placing fake buy and sell orders to manipulate the market. It also accused him of helping to cause the flash crash of 6 May 2010.

On that day, the Dow Jones index lost 700 points in a matter of minutes - wiping about $800bn off the value of US shares - before recovering just as quickly. The FBI claim that this was at least partly caused by his activity.

Extradition challenged

Mr Sarao's barrister James Lewis has attacked those claims, pointing to a growing body of opinion in the City and in academia that he could not, as the FBI allege, have "materially contributed" to the flash crash of 2010.

Hounslow in west London, from where US authorities allege Navinder Sarao caused the market to crash

Instead it's alleged that the flash crash happened because of a giant sell order placed by a US hedge fund called Waddell & Read, a conclusion previously reached by the US regulator, the Commodities & Futures Trading Commission.

Moreover, according to Mr Sarao's lawyers the US authorities are committing an "abuse of process".

Under extradition arrangements with the US, the accused can only be extradited from England if what they are accused of is a crime under English law. There is no English crime of "spoofing".

Because his lawyers have protectively advised him against any public statements, we know next to nothing about Mr Sarao's personality.

We know he has not been convicted of any other offences. We know he was regarded as bright and sociable at school. We know that according to his lawyers he has a severe version of Asperger's syndrome.

We also know that in 2010 he set up a company on the Caribbean island of Nevis called "Nav Sarao Milking Markets Limited" - though it had little to do with the dairy industry.

And we know that he made £30m without leaving his bedroom or indulging in a single ostentatious luxury. Those facts alone, though, aren't enough to condemn him.

Courtroom outburst

Navinder Sarao was locked up for four months from April to August last year because he could not meet bail conditions - because his assets had been frozen by the US authorities.

That prompted an outburst in court where he stood up behind the glass-fronted dock and turned to the courtroom protesting "how is this allowed to happen? I'm being punished for being good at my job!"

Inadvisable perhaps. But it didn't sound fake.

- Published5 February 2016

- Published4 February 2016

- Published20 May 2015

- Published6 May 2015