Why are South African students so angry?

- Published

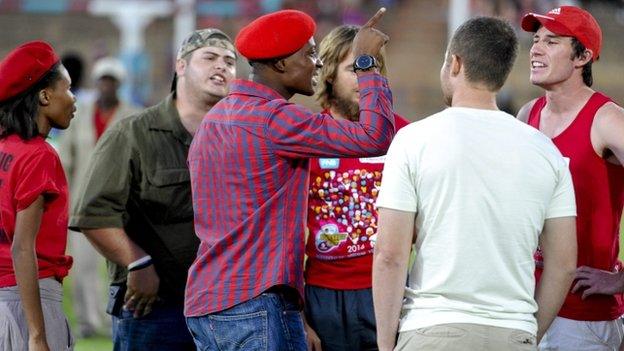

Students and spectators clashed at a university rugby match in Bloemfontein

South Africa's universities have faced protests and disruption, linked by a strong common thread. A place at a public university is now unaffordable for a large majority of potential students.

Last year saw a temporary fix and the government's budget, tabled in Parliament in February, will extend these stop-gap measures. But until the financial causes are addressed, the crisis will continue to escalate, with significant long-term consequences.

Protests have taken different forms. At the University of the Western Cape, students joined forces with trade unions to protest about debt and low wages. At the University of the Free State, a rugby match erupted in violence as spectators attacked student demonstrators.

At Pretoria University, students clashed violently over the policy for the language of instruction, and a shortage of student housing at the University of Cape Town led to a bus and artworks being burned and raw sewage thrown into lecture rooms.

Students at Tshwane University of Technology were sent home after violent protests

North-West University was closed after students from different political factions clashed.

These conflicts have been driven by a complex intersection of race and class, bringing to the surface issues that have remained unresolved over the 22 years since South Africa's first democratic elections.

The common thread is inequality and its consequences for student funding. South Africa is now one of the most unequal countries in the world and has a high and growing level of unemployment.

Average household income is about R75,000 a year (roughly £3,500), and about 70% of South Africans qualify for free state housing because they earn so little. Wealth, and the advantages in housing, healthcare and education that come with it, is sharply concentrated in the top two deciles of the population.

These economic circumstances have a profound effect on access to higher education.

Buildings were burned in a protest at North-West University in Mafikeng

The odds are heavily stacked against those from low income families because the quality of public schooling is highly variable.

Those that qualify to apply for a university place then encounter formidable financial barriers.

Very poor students may receive a bursary but this will not meet their full costs. Those from slightly better-off families find themselves in a trap, earning too much to qualify for state support, but far too little to be able to afford fees and accommodation costs.

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

For example, university is out of financial reach for the son or daughter of a registered nurse or schoolteacher, earning at the average for their profession.

A comparison between South Africa and England is instructive. Despite the claim that the student fee system is the most expensive in the world, a potential student from a low income family in England is in a far better position that a contemporary in South Africa.

For although English students will take loans of £27,000 to cover the fees for their three year degrees, these loans cover the full cost of tuition, and allow graduation without making any repayment.

Repayments are indexed to a graduate's earnings and the loan is written off after 30 years. While this is not technically a graduate tax, it feels like one.

Universities across South Africa have faced disputes and student protests

Their South African contemporaries, unless they are very poor, will probably incur up-front fees before they can register. They will be required to pay off outstanding debt before they can graduate and they will be expected to start paying back their loans whether or not they have a job.

While the graduate unemployment rate in South Africa is unknown, it is certainly several times higher than graduate unemployment in the UK.

Extreme inequality gives this situation a bitter edge. South African students from high income families may be significantly advantaged in comparison with their English contemporaries.

Take the case of a University of Cape Town student studying accounting, who plans to start her career working for a few years with one of the big firms in London; a common choice. Her degree will cost her about £6,800 over three years, in comparison with the £27,000 her English counterpart will have paid.

Students celebrated the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes in the University of Cape Town

Because, and in contrast with English universities, South African universities receive substantial teaching subsidies from the state, the South African graduate who starts work in London owes much less, in part subsidised by a government which also faces one of the highest rates of inequality in the world.

Given this, South Africa's present system of funding higher education is unsustainable.

Protests reached a crescendo in October and November last year as universities began to announce fee increases in excess of 10%. The government was pushed to negotiate a freeze on all fee increases and compensate universities in part for their projected losses.

This year's budget has earmarked contingency funds to extend the freeze on fee increases for a further two years, contribute to student debt relief and provide financial support for currently registered students.

But it is not a long-term solution. A place at a public university remains unattainable for a large majority of low and middle income families because, at their current levels fees are still far too high. And for high income families, the fees freeze is a welcome gift.

A Commission of Enquiry will make recommendations for the way forward, reporting in October.

Security guards on campus after the Tshwane University of Technology was closed

The National Student Financial Aid Scheme could be refinanced, so that its reach is extended to support middle income families.

There are also calls for "free" education. But different factions mean different things by this.

For radical student groups it may mean a call for no fees and full grants to cover living expenses. From the perspective of academic staff it may mean full state subsidy of teaching costs.

The common thread is the argument that, for a middle income country with significant economic and social challenges, higher education is far more of a public good than a private benefit.

The disruption of teaching, damage to buildings and facilities, clashes and widespread protests are in the context of South Africa's history. The legacy of the apartheid years taints all aspects of public life.

At the same time, old ways of funding access to university are proving ineffective.

Like many other countries, South Africa will have to make significant structural changes to its higher education system if it is to meet the aspirations of its students and the future needs of its economy.

Martin Hall is emeritus professor at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and former vice chancellor of the University of Salford in the UK.