Reaching the ships' crews cut off from learning

- Published

Sailing away: Ferry crews stay on board for a fortnight, often without access to the internet

If you were to think about bringing distance learning to a place with only patchy internet and where people were away from home for two weeks at a time, you might not immediately think of a cross-channel ferry.

But an education project is trying to improve the skills and qualifications of seafarers, in a way that is compatible with this floating workplace.

For any of us who have used ferries, it's often a rather insulated experience - less boat and more mobile tunnel or maritime service station. You drive on at one end, maybe spend some time in a cafe and shop, and then rush off the other end.

But what holidaymakers don't see is that the ship is where dozens of people live. Even though the ferries shuttle back and forth across the each day, crews stay on board for a fortnight at a time.

On a blustery crossing on a DFDS ferry on the Dover to Dunkirk run, you can see it's a way of life as much as a job.

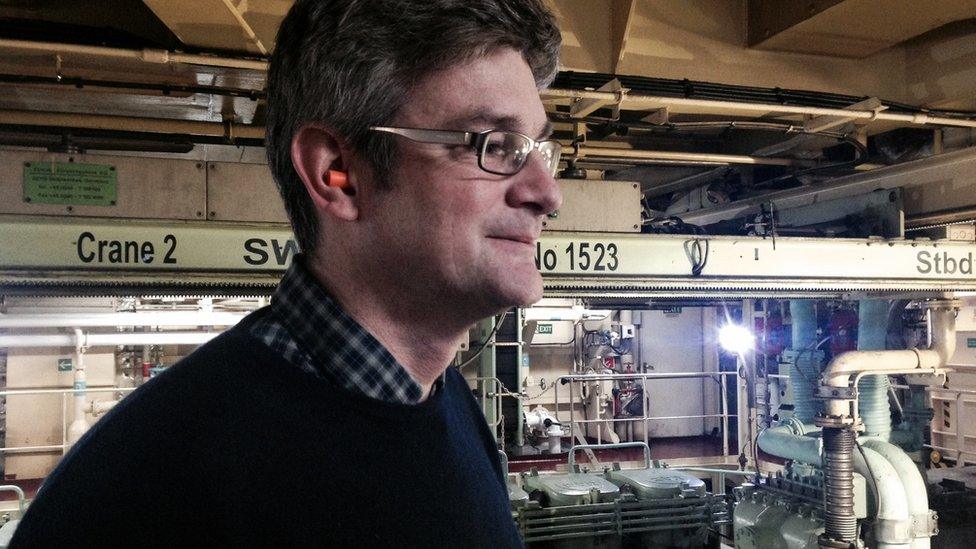

James Tweed says the public can be "sea blind", unaware of the lives of people working on ships

Training is important for the shipping industry. There are crew members from many different countries and backgrounds, with varying levels of skill and qualifications. Training is needed to keep up with changing technology and to protect safety.

But in terms of a workplace classroom, it is literally cut off.

An often unrecognised part of maritime life is the absence of reliable internet access for the crew. There isn't much bandwidth. And, quite often, for the crew, there is no online connection.

A project between shipping companies, the Marine Society charity and the RMT union has developed a customised approach to on-board lessons.

A software company, Coracle, has produced digital, distance-learning courses that can be used offline by the crew in their downtime.

And then, as soon as the ship is in reach of a signal, it can synchronise and update. It's a mobile phone app, but without needing to have a mobile connection.

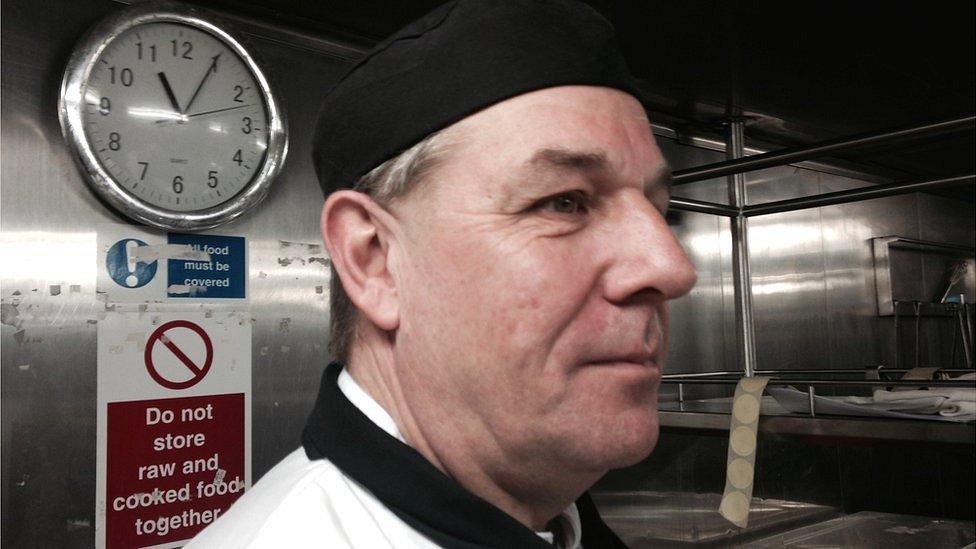

Head chef Les Potts says that his staff have to be seafarers as well as cooks

There are lessons in areas such as maths, literacy, English language and the rules of the sea, with courses such as Maths@Sea based around the specific needs of seafarers.

Delivering training for a crew at sea is a challenge for the shipping industry around the world.

And these @Sea courses have been shortlisted for an award that will be judged by the general secretary of the International Maritime Organisation.

James Tweed, the founder of Coracle, previously chartered oil tankers. He says one of the biggest lessons from this was how little the general public knew about the sea and the lives of those who work on ships.

He calls this "sea blindness". If you're reading this article on a laptop or a tablet computer, Mr Tweed says, it probably arrived from Asia after a month-long sea voyage. But it's a case of out of sight and out of mind for a public that never sees the journey.

"For an island nation, the majority of people have no idea what happens beyond the swimming-trunks' depth of the shoreline," he says.

View from a bridge: Ryan Booth, captain of a DFDS ferry between Dunkirk and Dover

The training project, delivering e-learning without the internet, he says, is filling a gap for an industry that badly needs help with new skills.

"The education technology world has missed them. It's invisible, because no-one knows what the industry looks like."

Shipping crews can have plenty of practical experience, but might well have few qualifications or ways to measure what skills might need to be updated.

Mr Tweed gives the example of the fishing industry.

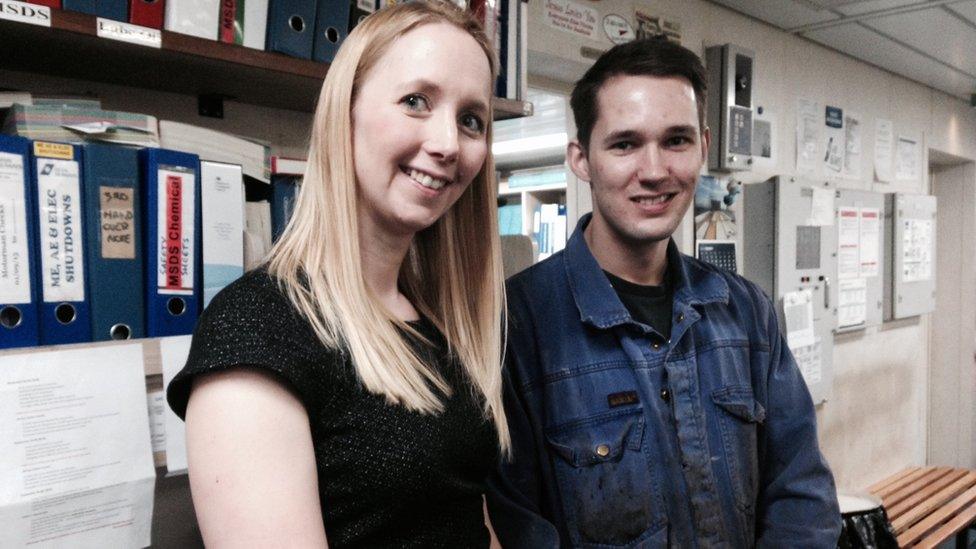

Nicola Steer, in charge of training for DFDS, and apprentice Joe Butler

"The reality of the fishing fleet decline is really profound. You've got a group of people, generation after generation, following a particular path, and in many cases their industry has just gone.

"They understand the life at sea, but educationally the system has moved on.

"How do you get someone who dropped out of the education system as a teenager back into it, so they can qualify in an industry that they're suited to?"

Nicola Steer, training and human resources officer for DFDS, says there are often no real equivalences for the qualifications in the shipping industry.

A ship's captain will have studied in maritime college, taken tough exams and gathered years of experience at sea - but when they apply for a job on shore, it isn't recognised in the same way as a university degree.

Global trade depends on shipping: Loading containers in Tianjin, China

From the perspective of the Danish-based shipping company, Ms Steer says, the training project is very valuable. It allows crew members to improve themselves and advance their careers.

She says the company wants to "create a culture where everyone is learning".

But it's also a way for it to develop talent from within their own ranks.

When she goes to careers fairs, she says, there is often little understanding of jobs in the shipping industry. Recruitment can be a challenge, so training existing staff becomes more important.

The crew on board a ship occupy their own self-contained world, with their own sleeping quarters and places of work, such as the hi-tech airiness of the bridge, the rattle of the kitchens and the heat and noise of the engine rooms.

Head chef Les Potts says people working in the ship's galley have to be both cooks and seafarers.

Ship's engineer Rihards Ellers is responsible for the huge engines on the ferry

Getting the right crew can be a challenge, and he says there are big benefits from being able to train their own staff.

You also have to be ready to make an awful lot of fish and chips. Mr Potts says that no matter what they try on the menu, it's fish and chips that remains the most popular.

Day-release courses are not possible at sea, so the ship has to become a floating training centre.

The ferry is a self-contained world for crews who live and work on board

Joe Butler is an apprentice on board, training to be a marine engineer. His new classroom is the engine room, where he learns about the workings of the huge, thumpingly loud engines.

Ship's engineer Rihards Ellers, sitting in front of a bank of computer screens, says his job is becoming increasingly technical and staff need to keep updating their skills.

There is also another huge difference in these working lives. And that's the sea itself and all its unpredictability.

Ms Steer has been promoted to a job on shore, but she says she still misses the unique life of a ship at sea. "I absolutely miss it every day," she says.