Will smart meters be worth the money?

- Published

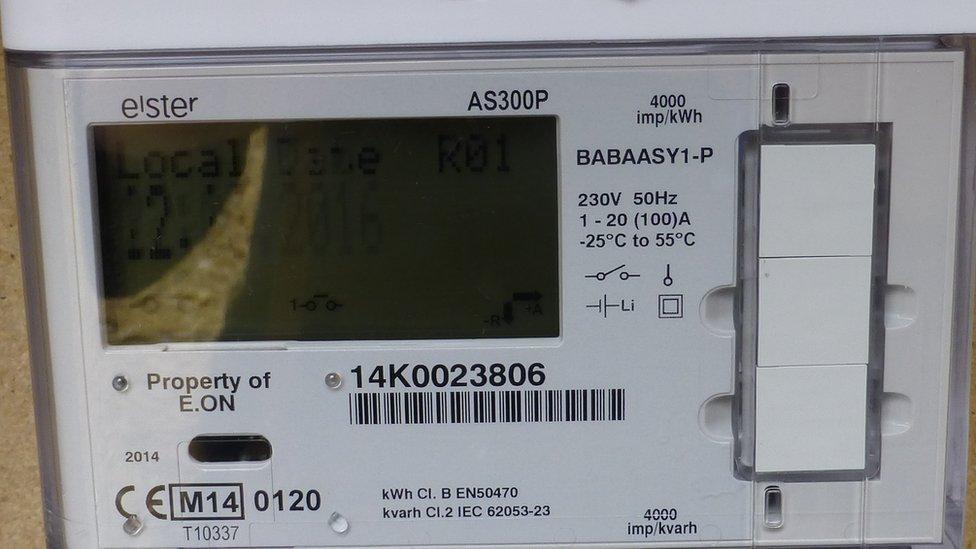

Millions of energy users in Britain are about to get a new metering system - smart meters - technology which has been rejected by Germany and found not to be cost-effective by other nations.

Smart meters send information on energy usage directly back to the energy supplier, which eliminates the need for meter readings.

Crucially, they also let the customer know just how much electricity or gas they are consuming during the day. This revelation is expected to change our behaviour, so that we switch off lights, turn down heating, and generally use less energy.

Overseas experience

The EU has said that all its members must provide smart meters by 2020 as long as there is a positive economic case to do so.

Germany employed accountancy firm Ernst and Young to conduct a cost-benefit analysis and they concluded it did not make economic sense, because most householders did not use enough energy to make it value for money. As a result, Germany declined to stage a mass roll-out.

Other countries have adopted smart meters with varied success. Auditors in Australia and Canada found it was too expensive.

Andrew Evans, from the auditor general's office in Victoria, Australia, said there would not be any overall benefit to consumers, and the net cost was $320m (£170m) paid by consumers through higher energy bills.

The British government has committed to getting 53 million smart meters into our homes and small businesses by the end of 2020, at an estimated cost of £11bn. That does not include Northern Ireland, which is still assessing whether smart meters would be in consumers' interests.

Changing behaviour

Maureen Fenlon with her in-home display

There are already two million meters installed in households and businesses in the rest of the UK.

Pensioner Maureen Fenlon and her husband Viv opted to have smart meters installed in their Lincolnshire bungalow a year ago. Mrs Fenlon was proud to show me the small "in-home display" which shows the cost of electricity and gas used during the day.

She said seeing the real cost of using appliances has encouraged her to use her microwave more than her oven, which has saved money on bills.

That kind of behaviour may cut our bills, it is claimed, by an average £26 a year per household up to 2020. According to government estimates, that could mean a total saving of around £6bn by then.

The Department of Energy and Climate Change says: "Smart meters will help families and businesses take control of their energy use, bringing an end to estimated bills and helping bill payers to become more energy efficient."

However, the cost of the roll-out is high, and the estimated savings rely on millions of us being willing to change our behaviour.

Meanwhile, the second stage of introduction is running late. This involves a second generation of smart meters, and a new national communications network which will allow the transmission of data between smart meters and all energy suppliers.

Hitting the elderly?

There has been criticism of how the entire smart meter project has been planned.

In other countries, a central administration has handled the roll-out whereas in the UK, the government left it up to the energy companies.

Some homes do not get enough wireless signal for the current generation of smart meters to work.

If someone like Mrs Fenlon switches suppliers today, the in-home display may not work with the new supplier's technology; the first-generation smart meter effectively becomes "dumb". That should change in the next couple of years when the new communications network is up and running.

The so-called big six energy suppliers are hoping to introduce a new kind of pricing to go with smart meters, a system used elsewhere in the world called time of use tariffs.

This could mean that you are charged much more at peak times, say between 16:00 and 20:00, for using electricity. The idea is that you are being nudged to use your appliances when it is cheaper.

Critics worry that this might have damaging effects on vulnerable groups of people such as the elderly and those on low incomes.

According to Stephen Thomas, Emeritus Professor of Energy Policy at the University of Greenwich, older or vulnerable people who are faced with extra high costs of using energy on a cold winter evening may choose to switch off and be cold.

The answer is that these "time of use" tariffs will be purely voluntary, according to Rosie McGlynn, director of new energy services at Energy UK. She argues people will be able to plan ahead better and save on their bills when they have a smart meter, and those currently on pre-payment meters will pay lower prices than they do now.

Smart meters are not compulsory, although the publicity campaigns do not give that fact much prominence. The energy companies are footing the bill for installing smart meters, but they acknowledge they will pass costs on to the customer. So, even if you do not want one, you are going to be paying part of the £11bn cost.

Listen to the Moneybox special on smart meters on BBC Radio 4 at 12:00 GMT on Saturday, 26 March