The economics of steel? Pretty bad

- Published

- comments

In markets, a "buffalo jump" is the moment the price of a commodity rises suddenly before slumping back to its more normal steady state - which for products such as steel has been down, down, down.

It's based on the tradition of Native Americans to herd buffalo towards steep cliffs and their ultimate death.

The price of a tonne of steel is of vital importance: too low and thousands of jobs are put at risk, as they are today for steel workers from Port Talbot to Rotherham, Corby to Shotton.

Global oversupply and declining demand have seen prices slump by more than half in the last year.

Of all the steel produced in the world, only two-thirds is actually being used, a low "utilisation" rate.

But the price of steel has actually been rising in the last few weeks, creeping up to about £285 per tonne, a rise of £30, according to Platts, the commodities pricing agency.

Is this the dawn of some sunnier weather in commodities, including steel, that have been trapped in a bearish cycle - and possibly better news for the British steel industry?

Or just some brief sunshine ahead of further stormy showers?

In other words, a "buffalo jump".

Making a killing

The fundamentals are looking poor for steel.

This is in a note from the Barclays' commodities analyst, Kevin Norrish, who used the dreaded "jump" term to describe the recent price rise.

"Investors have been attracted to commodities as one of the best-performing assets so far in 2016," Mr Norrish said last week.

"However, in the absence of any concerted fundamental improvements, those returns are unlikely to be repeated in the second quarter, making commodities vulnerable to a wave of investor liquidation."

In other words, investors have bought in to make a killing in markets that collapsed in the first three months of the year.

And they could get out again just as quickly.

As Mr Norrish suggests, the fundamentals are working against any prolonged increase in the price of steel.

The biggest reason is China, which produces half the world's steel.

The rise of that country as a steel-exporting country is remarkable.

In 2003, China exported 7.2 million tonnes of steel - about 5% of the world's trade in the commodity - mainly to other Asian markets.

By 2015, that figure had risen to 107 million tonnes, a figure that is still rising as China reacts to its own slowing economy (and therefore dip in demand for steel) with an aggressive push into overseas markets.

Producers in Europe, America and India complain that Chinese steel is subsidised in a way not open to domestic operators, depressing prices further.

Swiss bank UBS estimates that in the first 10 months of 2015, the 100 top steel producers in China lost $11bn (£7.6bn) - much of it covered by state subsidies.

Catching pneumonia

The Chinese authorities have agreed that there is an oversupply problem and have pledged to close unproductive plants, a message which some believe has led to the recent bounce in global steel prices.

But statements from the central authorities are not the same as action on the ground, where huge steel factories are important local employers.

And even though Chinese steel production is slowing - down by about 4%, according to the latest figures - exports are still increasing, up by about 4% year-on-year in early 2016.

What China does in steel exports is vital to the UK steel industry - especially "long products", the lower technology steel output that is used by the car industry, building sector and transport.

For some perspective, in 2013 China produced nearly 800 million tonnes of steel.

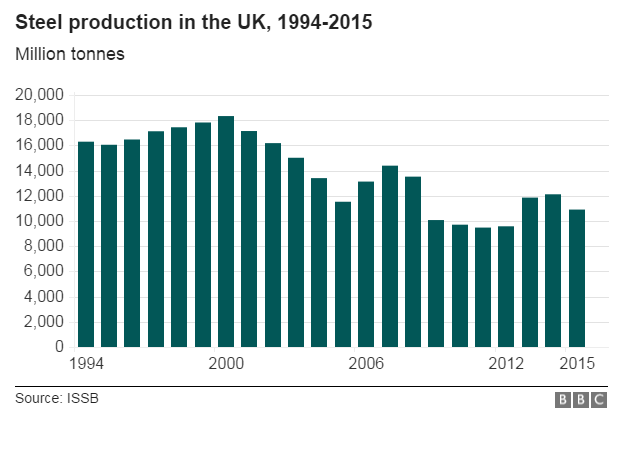

The UK produced 12 million tonnes - and steel production now makes up just 1% of Britain's manufacturing output and 0.1% of all the UK's economic output.

The value of the industry to the UK economy has fallen by a quarter since 1990.

If China sneezes in steel, the UK does not so much catch a cold as pneumonia.