Using tiny predators to tackle agricultural pests

- Published

It may be small, but amblyseius cucumeris makes its presence known

Amblyseius cucumeris may have a posh name, but it is a total thug.

A tiny mite, just 0.5mm long, it is a fearsome predator.

It eats a type of insect called thrips. These are small winged insects that generally feed on plants.

Thrips are a major agricultural pest around the world, and can damage whole fields of crops, literally sucking the life out of them. But introduce amblyseius cucumeris and you have a bloodbath and then no thrips.

For farmers who wanted to protect their fields from thrips - and the many other pests out there - the method developed in the 20th Century was to spray liberally with chemical pesticides.

But as authorities around the world have in recent decades increasingly clamped down on the usage of such products, this has led to the creation of a growing multi-million dollar global industry - biological pest control.

Biological pest control is the means of controlling pests using other living organisms - breeding ladybirds to eat aphids, for example.

The mites can be simply shaken onto plants

While it may come as a surprise to some, the East African nation of Kenya is at the forefront of the sector.

The country is helping to lead biological pest control development due to the importance of agricultural exports for the Kenyan economy.

In 2013, Kenya exported $355m (£250m) of agricultural products to the European Union (EU), from fruit and vegetables to fresh flowers, grown by hundreds of farmers.

And as the EU has over the years increasingly banned or limited the use of chemical pesticides, Kenya's farmers have had to follow suit to continue selling their produce in Europe.

As a result, Kenya has increasingly turned to biological pest control to ensure that its agricultural exports to Europe are still in the best possible condition, be they green beans or bunches of roses.

'Longer time'

Henry Wainwright and his wife Louise, both agricultural scientists, set up their biological pest control business, Real IPM (Integrated Pest Management), seven years ago.

Both are British citizens who had moved to Kenya to work for another such business called Dudutech, before starting up their own company in 2009.

Henry Wainwright's business now employs 230 people in Kenya

They now sell, breed or grow seven different bio-control agents, ranging from the aforementioned amblyseius cucumeris to Real Metarhizium anisopliae 69, a fungus that kills insects, including types of flies and beetles, and Real Bacillus subtilis, a bacterium that attacks mildew.

Mr Wainwright says that while Real IPM's products are far more environmentally friendly than chemical treatments, farmers have to be more patient before they see the benefits.

"Unlike chemicals, where you see the results soon after spraying, bio agents works over a longer time," he says. We're talking weeks rather than days.

Real IPM, based 50 miles north east of Kenyan capital Nairobi, now employs 230 people, including 30 university graduates.

Other treatments see slow-release bags of mites attached to plants

Some 75% of its sales are in its home market, with the remainder exported to Ethiopia, Tanzania, Ghana and the UK.

Real IPM staff train Kenyan farmers on how to use the products, and the company has a research partnership with the Nairobi-based International Centre for Insect Physiology, and UK-based business Syngenta Bioline.

Mr Wainwright, 64, says: "We decided to do this business in Kenya due to, among other things, the tropical, warm climate; availability of the right personnel; and a good work ethic that seems to thrive here.

"As awareness grows we are likely to see many more farmers, including small holder growers who greatly contribute to Kenya's fruit and vegetable exports, embrace IPM in pest and disease control."

'Local production'

At Dudutech, which is Real IPM's larger competitor, 13 different bio-control agents are now produced, and it spends $1m a year on research. Typically it takes three years before a new bio-control agent receives regulatory approval.

The company was set up in Kenya in 2007 by Dick Evans, a businessman of British origin who then owned one of the country's largest flower and vegetable growing businesses. In the Swahili language "dudu" means insect.

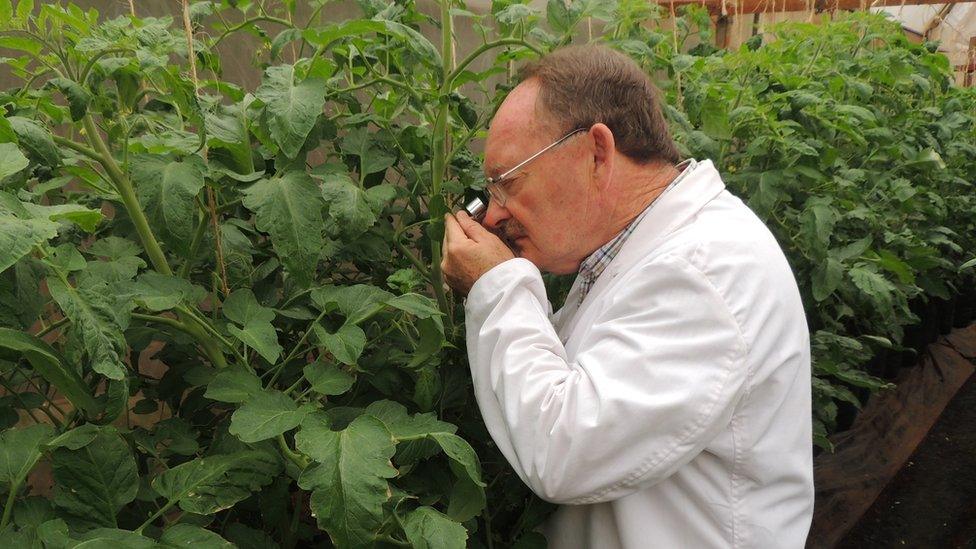

Dudutech invests heavily in research

Dudutech is today a subsidiary of Kenyan agricultural business Flamingo Flowers, which in turn is owned by US investment firm Sun Capital Partners.

Tom Mason, Dudutech's managing director, says the business now employs 340 people, all Kenyans, and including 40 scientists.

The company also had partnerships with UK agricultural research organisation Rothamsted Research, Greenwich University in London, and the University of Virginia.

Mr Mason adds: "That aside, we do not buy production technologies from outside, we do our own research, and all the agents we produce are sourced locally."

Kenya is a major grower of roses for the European market

However, all this research costs money, and bio-control agents are typically twice the price of chemical pesticides.

In Kenya, this means it costs between $200 and $400 to treat one acre of crops using biological pest control, compared to between $100 and $200 using chemical spray.

Back at Real IPM, Mr Wainwright says the increased cost is well worth it if it means you can export your roses, for example, to the UK.

But wherever a farmer sells his roses, Mr Wainwright says that no man should want to give pesticide covered roses to his girlfriend.