What's the deal with offshore funds?

- Published

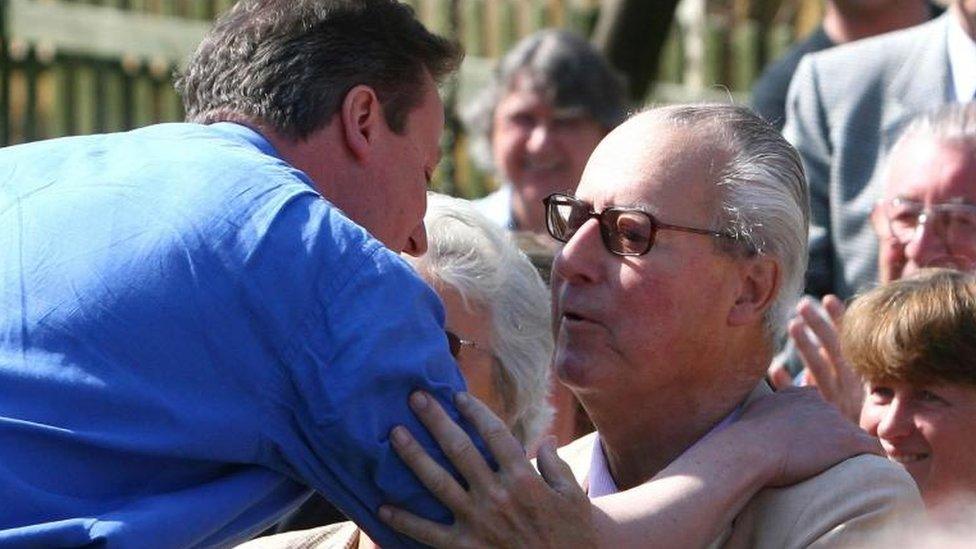

The debate over David Cameron's interest in an offshore fund set up by his late father has shed a light on these operations - and how common they are.

Thousands of similar funds, or companies, have been set up for various reasons although, ultimately of course, their aim is to make money.

Those on one side of the argument will argue that these funds exist, and are based offshore, primarily owing to the opportunity to escape paying certain taxes.

The opposing argument is that this decision is purely based on rational business grounds, by finding a way to attract investors from around the world and for the fund to perform to its peak.

Performance

Blairmore Holdings is an open-ended fund - that means there is no final date at which investors will all take out their money.

It was set up in the early 1980s and named after Blairmore House - where the Prime Minister's late father Ian Cameron was born. Mr Cameron senior was a director in the company.

Incorporated in Panama, the fund operated from the Bahamas, until its operation was moved to Dublin in 2010.

It is a dollar-denominated fund. In other words, the currency in which the fund is held is the US dollar. This provides security for investors owing to the stable nature of the dollar compared to some other currencies internationally, as it is a currency that would generally hold its value.

The fund rose sharply in value in the 1980s and 1990s before taking a bit of a hit during the financial crisis. It then recovered but has seen a steady decline since.

It is fair to say that, compared with other funds, it has not recorded a stellar performance in recent years, compared to other funds.

Even so, David and Samantha Cameron bought their holding in April 1997 for £12,497 and sold it in January 2010 for £31,500.

Investors can still put money in - the minimum is $100,000 (£71,145) - and they are expected to pay a 1% management fee. The latest figures show the fund is worth just over $30m (£21.3m)

Tax havens

So, why set this fund up to operate out of the Bahamas, rather than London or New York?

David Cameron argues that it was set up so that people who wanted to invest in dollar-denominated shares and companies could do so after a change in the rules governing this area.

Supporters of offshore financial centres like the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands and others say that funds are set up in these countries to provide a neutral ground for global trade and investment.

Investors put in their money and pay tax where they are a tax resident. After that their investment sits in a fund until they take it out.

The low-tax or no-tax regimes, known as tax havens, can provide an inexpensive home for that money for all concerned, while the fund operates, until the investors pay tax when they take their money out.

Investors in Blairmore, for example, are liable to income tax on the dividends they receive and capital gains tax on whatever profits they earn, over a certain threshold.

The location also allows companies from across the world to do deals in a neutral space where one of them will not be put at a disadvantage. The offshore industry claims the secrecy it is famous for is essential for facilitating these transactions.

Others will say it is morally wrong - but not illegal - for these funds to pay no tax, or hardly any tax, in the country where it is based while they are operating. So, the company would pay little or no corporation tax on any profits it makes from its investments, allowing it to potentially pay out more to investors.

This would not be the case if, for example, the funds were based in the UK. Opponents also object to the opaque nature of these funds and whether the money is subject to inheritance tax.

Hence, there is no illegality regarding offshore funds such as Blairmore, but there is a debate over whether the system has any moral justification.

- Published8 April 2016

- Published7 April 2016

- Published6 April 2016